When the President of Rwanda was killed in a plane crash on 6 April 1994, Hutu extremists embarked on a killing spree, massacring over 600,000 Hutu moderates, political opponents, and most importantly, Tutsis, in about a hundred days. The United Nations (UN) peacekeeping mission deployed in Rwanda could neither prevent nor halt the genocide. Both this mission and the UN Security Council have been the subject of heavy criticism regarding their actions prior to and during the Rwandan genocide.[1] The UN commissioned several inquiries into the role of the international community in Rwanda. However, one aspect has been largely overlooked by scholars. In neighbouring Uganda, another, much smaller mission was deployed: the United Nations Observer Mission Uganda-Rwanda (UNOMUR).

In general, this mission has received very little attention in historiography. It has been forgotten by journalists, scholars and policymakers alike. The mission is only mentioned occasionally in works on Rwanda and almost exclusively in a contextual manner. Therefore, this article will delve into UNOMUR and the actions of its observers during the Rwandan genocide. It will show that it is a missed opportunity to leave this mission out of the debate on the response of the UN to the Rwandan genocide, especially for Dutch historians and other interested parties, as a total of twenty Dutch soldiers served with UNOMUR.

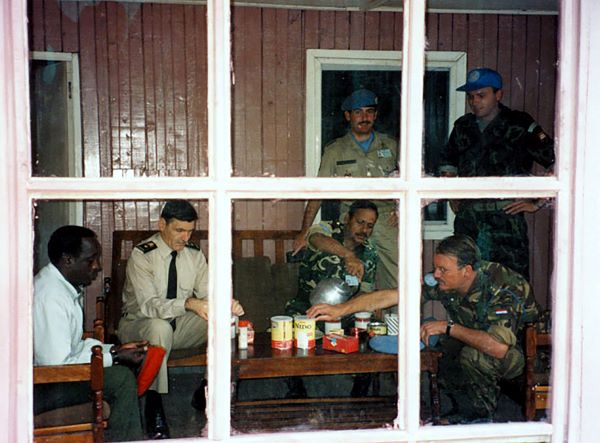

UNAMIR’s commander Brigadier General Roméo Dallaire (second from the left) speaks with UNOMUR observers. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Rwanda

Before the actions of UNOMUR during the Rwandan genocide can be analysed, the history of the Rwandan conflict has to be understood. The two main ethnically categorised groups in Rwanda were the Hutus, composing around eighty-five per cent of the population, and the Tutsis, who make up for less than fifteen per cent. Both groups belong to the Banyarwanda, or ‘people of Rwanda’.[2] Originally, these were socio-economic groups. A Tutsi was a person ‘rich in cattle’, while a Hutu was a subordinate. Social mobility was possible but became less and less common as the Tutsi elite tightened its grip on the Rwandan state.[3] When the Europeans arrived, first the Germans, and then after the First World War, the Belgians, they found a highly centralized state. The Belgian colonial administration maintained these existing power structures but institutionalized a social order. They favoured the Tutsis, elevating many to positions of power and education. On the other hand, many Hutus were conscripted into forced labour. The opportunities for Hutus to climb the social ladder were thwarted by the Belgian authorities, who registered every Rwandan’s group. The original socio-economic categories now became hereditary, and racial.[4]

Under pressure from the UN, Belgium gradually opened up the political system in the 1950s. Political parties were founded, but after years of ‘divide and rule’, these parties were mainly formed along ethnic lines. The strive for independence was a common goal, but the major Hutu party also challenged the superior position of Tutsis in Rwandan society. Elections were held in 1961, which resulted in a decisive victory for the Hutu party.[5] This period was marked by skirmishes between Hutus and Tutsis, but an invasion by Tutsis from Burundi in 1963, which nearly led to the capture of Rwanda’s capital Kigali, resulted in mass repression against Tutsis by the Hutu regime. A mass exodus of Tutsis to neighbouring countries followed.[6] By 1990, there were over a million Banyarwanda living in Uganda. Amongst them were those who had lived there ever since the colonial powers drew the borders of Central Africa, economic migrants from the early 20th century, and post-independence refugees fleeing the ethnic violence in Rwanda.[7]

The Banyarwanda would have a significant influence on Ugandan history. The Rwandan regime under President Habyarimana, a Hutu, wanted to prevent the Tutsi refugees from returning to Rwanda, so he closed the border with Uganda in 1982. The Ugandan government under Milton Obote also did not recognize the refugees. As a result, the Banyarwanda were trapped in Uganda, oppressed and persecuted by the local authorities.[8] Around the same time, several rebel groups emerged to challenge the regime of Obote. Amongst them was the National Resistance Army of Obote’s Minister of Defence: Yoweri Museveni. The ensuing civil war resulted in the installation of Museveni as President in 1986, at which point around twenty per cent of his forces were Banyarwanda.[9] Many of these men, with five years of experience in warfare, joined a group of Banyarwanda intellectuals, and formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). The RPF was a militant organisation, dedicated to overthrowing Habyarimana and to establishing a democracy in Rwanda, and allowing refugees to return.[10] Over the years, Habyarimana’s regime had not only been discriminatory against Tutsis but had become increasingly oppressive against Hutus as well, favouring only those from his home region. As more Hutus were growing discontent with the regime, some joined the otherwise predominantly Tutsi RPF.[11]

On 1 October 1990, the RPF invaded Rwanda in an attempt to overthrow the Habyarimana regime. Half of the 7,000 soldiers came from the Ugandan army. They had brought their personal equipment with them, while larger calibre weapons were taken from Ugandan depots.[12] Despite these preparations, and initial territorial gains, the attack did not fare well. Habyarimana rallied support from Belgium, France, and Zaire, and by the end of the month the RPF was practically defeated. The remaining rebels pulled back into Uganda and military command was taken over by Paul Kagame, a close friend of Museveni’s. Under Kagame, the RPF adopted a strategy of guerrilla warfare in north-western Rwanda, where they were protected by the Virunga mountains and could acquire weapons and supplies across the Ugandan border.[13]

Establishing UNOMUR

Over the next few years, the conflict continued to simmer, with both sides occasionally resuming hostilities. Almost immediately after the invasion, however, peace talks had begun between the RPF and the Rwandan government, mediated by various countries. After almost three years of negotiations, the parties signed the Arusha Peace Accords on 4 August 1993. Uniquely, these accords not only formally ended the war, but also covered the new political institutions, the return of refugees, and the integration of both armies. The accords were an attempt to prevent any further conflict from erupting.[14]

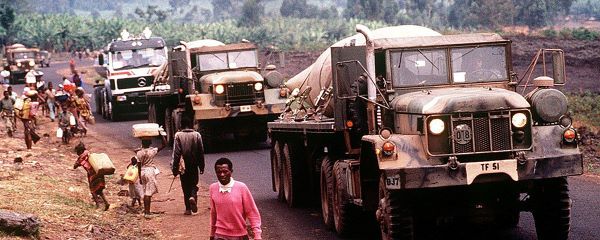

RPF attacks led to displacement of hundreds of thousands of Rwandans. Photo Government of Canada

During the negotiations, in February 1993, the governments of both Uganda and Rwanda requested that the UN deploy unarmed military observers to their shared border. Providing neutral eyes in the border area could forestall accusations of Ugandan support for the RPF, prevent weapons from entering Rwanda, and strengthen the peace process overall.[15] This seemed to be a sensible solution to the problem of the close links between the RPF and Uganda, but it took the Secretary-General three months to present a plan for such mission, and another month for the Security Council to take action. On 22 June it adopted Resolution 846, establishing the United Nations Observer Mission Uganda-Rwanda (UNOMUR). Eighty-one unarmed United Nations military observers (UNMOs) were deployed on the Ugandan side of the border, opposite the territory controlled by the RPF. The mission is described as a ‘temporary confidence-building measure’ and is placed in the wider framework of efforts to put an end to the conflict in Rwanda. The mission’s mandate was to monitor the border to verify that no military assistance, weapons, and ammunition reached Rwanda, while not restricting civilian transit.[16]

The original plan

Despite the resolution being passed in June, the UN Secretary-General could only report the full deployment of UNOMUR by the end of October. The Canadian Brigadier-General Roméo Dallaire had been appointed to lead the mission as Chief Military Observer, but he was hindered by a lack of information available on the conflict, by a lack of resources provided by the UN, and a lack of cooperation with their Ugandan hosts.[17] The eyes of the world were focused on other missions, such as UNPROFOR in Yugoslavia, and when the UN established a peacekeeping mission in Rwanda itself in early October, the attention and interest in the observers in Uganda began to fade.

The problems that Dallaire and his colleagues encountered during the preparation of the mission, continued throughout the deployment. Technically, UNMOs are ‘loaned out’ to the UN, meaning that they are responsible for their own outfit, but everything else is arranged and paid for by the UN. But when the quartermasters had arrived in the mission area in September 1993, nothing had been arranged yet. There was no military base or compound ready to house the mission, so they rented a small estate on a hill in Kabale to function as mission headquarters. Housing also had not been provided, so the observers rented their own accommodations. It even took the UN months to deliver the characteristic blue berets.[18] The UN had ambitious ideas about UNOMUR and its role in bringing an end to the Rwandan conflict, but the observers had to start from absolutely nothing.

UNOMUR was tasked with monitoring about four-fifths of the Ugandan-Rwandan border, opposite the RPF-controlled area, some 120 kilometres of hills and forests, but had only eighty-one observers at its disposal. Around twenty of them were stationed at the mission headquarters in various roles. The remaining observers could not possibly cover the whole border area, so they set up observation points at the two main roads crossing into Rwanda.[19] This is what prompted the Secretary-General to report the full deployment of UNOMUR in October. It was not until March that three secondary observation posts were established, with a sixth and a seventh following later.[20]

The rest of the territory was to be covered by aerial and mobile patrols. But the two helicopters arrived only in March, and one of them was always kept in reserve. There was also a shortage of vehicles, which was also only partly solved, again, in March. Most of these vehicles were flown in from other UN missions, where they clearly had already been used extensively.[21] The lack of supplies demonstrated UNOMUR’s place in the order of allocation of UN resources. And even with these vehicles, patrolling the hilly and forested area was a challenge. The observers had been provided with outdated maps, so they had to be careful not to accidentally wander into minefields or enter Rwanda, which was specifically prohibited.[22] The Ugandan army was also an obstacle. They had pledged to offer escorts and security for the unarmed observers. In reality this meant that the observers needed the blessing from their Ugandan hosts for every patrol. This not only violated the unrestricted freedom of movement that UNOMUR was supposed to have, but whilst the observers were to verify that no military assistance reached Rwanda, the Ugandans themselves knew the schedules and locations of the patrols.[23]

As mandated, the UNMOs observed the cross-border traffic. The majority consisted of ordinary civilians crossing the border, either to visit family or to go to work, but they also saw trucks carrying food, fuel, and people into Rwanda. This was not prohibited and, given the connections between the people on both sides of the border, it also was not conspicuous. Due to the severe lack of manpower, UNOMUR could only occasionally do a complete check on these trucks, in search for weapons or ammunition.[24]

So, did they find any ‘military assistance’ crossing into Rwanda? The answer is simple: no. Not one of the observers interviewed for this article found weapons or ammunition destined for Rwanda, nor did they hear of colleagues making any such discoveries. In the dozens of situation reports sent by UNAMIR to the Department of Peacekeeping Operations, only two observations are worth mentioning here. On 26 January 1994, a patrol found grenades hidden near the border, and on 30 May, a military vehicle carrying seven armed men crossed into Rwanda. There is no mention of any follow-up to these reports.[25]

UNOMUR observers carry out checks at a Ugandan-Rwandan border crossing. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Even if any material had been found, the UNMOs were not allowed to seize it. In fact, they were not allowed to intervene at all. At best, they could file a report, without any reassurance that such reports would make a difference.[26] Neither were they allowed to enter Rwanda, which explains why no one followed the military vehicle across the border in May. UNOMUR simply did not have the capacity to cover the whole area. Therefore, there is no way of knowing whether indeed any military assistance crossing into Rwanda ever occurred, or if the RPF, with its superior knowledge of the area, simply evaded the observers.

Improvising along the way

After the establishment of UNOMUR, two events would significantly alter the context in which the observers were to operate. First, the UN established a second mission, this time in Rwanda itself, in early October of 1993. Second, in April of the following year, the President of Rwanda was killed, which signalled the beginning of the Rwandan genocide. This article describes how the observers in Uganda had to adapt to these new circumstances, how they reshaped the purpose of the mission, and how, despite all the shortcomings and limitations described above, they made themselves much more useful than history gives them credit for.

As mentioned before, the Arusha Accords were not just a peace treaty. They covered the return of refugees, the integration of the two armed forces, and the establishment of a transitional government to pave the way for elections. To assist in the implementation of these agreements, the UN established the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR). This was not an observer mission, as in Uganda, but a peacekeeping mission which included three infantry battalions.[27] It was supposed to play a much more pro-active role in the Rwandan conflict than UNOMUR. Whilst the preparations for UNOMUR were made with hardly any knowledge of the area, there now were officers who were already familiar with this conflict. General Dallaire was made Force Commander of UNAMIR and brought two of his colleagues with him from Uganda. UNOMUR was incorporated into UNAMIR, leaving an Acting Chief Military Observer in charge in Uganda. Originally a stabilising factor between Uganda and Rwanda, patrolling the border and providing neutral eyes in the area, UNOMUR now became an intelligence source on the flanks of UNAMIR. Dallaire used their observations to defuse any tensions and accusations between Rwanda, Uganda, and the PRF. Their presence on the border assured that Dallaire could easily travel to Uganda and negotiate with the local authorities.[28]

On 6 April, 1994, the airplane carrying President Habyarimana and his Burundian counterpart was shot down by unknown assailants. In the chaos that followed, Hutu extremists, wielding mostly machetes and farming equipment, committed a genocide on the Tutsis of Rwanda, which lasted for three months and left over 600,000 dead. While the Tutsis were clearly the targets of the genocide, after years of hate speech against the ‘cockroaches’, the extremists also went after political opponents. They first killed Hutu moderates, particularly intellectuals and politicians, and other opponents of their extremist rhetoric. One of the first victims of the genocide was the Prime Minister, a Hutu and natural successor to Habyarimana, and the ten Belgian peacekeepers who were protecting her.[29]

Consequently, the Belgian government withdrew its contingent, which made up the core of UNAMIR’s military force. The UN decided that without its best-equipped troops, UNAMIR could no longer fulfil its task. The mission was reduced by almost ninety per cent, and the remaining 270 men were tasked with brokering a ceasefire ‘between the parties’, without specifying who exactly these parties were.[30] Whilst there was a genocide being committed, the UN was in disarray with no plan on how to halt it. In this chaotic situation, the observers of UNOMUR remained in their positions on the border. Not only did they continue their mission, but they also expanded their operations, conducting several tasks not included in their original mandate.

In response to the genocide, the RPF quickly moved out of their positions in northern Rwanda and conquered the eastern half of the country. This brought the entire border area with Uganda under their control. UNOMUR therefore expanded its mission area, even though it barely had the means and manpower to cover the old positions.[31] From their observation posts, the UNMOs witnessed the first advances of the RPF. They were not allowed to enter Rwanda, but NGOs were. Many operated from Uganda and shared their experiences with the observers. In turn, they shared their perspective on the RPF offensive with Dallaire.[32]

During the war in Rwanda, the airport in the capital, Kigali, was caught up in heavy fighting between the RPF and government forces. Dallaire was forced to close the airport, leaving UNAMIR and NGOs cut off from support and with no way of evacuating its personnel in case of emergency.[33] He needed a secondary logistical base in the region. UNOMUR already had a small liaison office in Uganda’s capital, Kampala, and Dallaire decided to expand it to the airport at Entebbe, with observers from both missions. With their assistance, Entebbe became a crucial logistical hub.[34] During the genocide, only two humanitarian organisations remained in Rwanda: the Red Cross and Médecins Sans Frontières. Other NGOs, such as the World Food Programme and UNICEF, left for Uganda. In their attempts to provide aid to the many victims in Rwanda, they set up their logistical offices in Kabale, near the border with Rwanda.[35] These NGOs had supplies flown to Entebbe, from where UNOMUR escorted the convoys to Kabale or directly to the border. There, UNAMIR teams were waiting to take over.[36] UNOMUR coordinated the convoys and escorts, but was also involved in facilitating the humanitarian efforts. Together with UNHCR, UNMOs organised meetings at the UNOMUR headquarters. There, NGOs could share information and coordinate their activities. After a few weeks, around fifty different NGOs were present at these sessions.[37]

Humanitarian aid was needed for Rwanda and neighbouring countries. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

Humanitarian aid was not only needed in Rwanda itself. The war and the RPF’s rapid advance led to an exodus of some two million Hutus to neighbouring countries. Around 800,000 ended up in refugee camps in the Zairean town of Goma.[38] The airport there was too small to accommodate the arrival of the necessary aid, so again Entebbe became a key logistical hub, and again UNOMUR supported the operations of the NGOs. By mid-July, the United States and Canada had established humanitarian operations for the camps in Eastern Zaire. Both used the airport at Entebbe extensively.[39] The UNOMUR liaison team assisted to coordinate and ensure that the supplies were delivered to the right places.[40]

Furthermore, with the airport in Kigali closed, journalists needed UNOMUR assistance to enter Rwanda. They would land at Entebbe and, like the food convoys, be escorted by UNMOs to the border. There, UNAMIR escorts would take over and accompany the journalists to Kigali.[41] Supported by the UN troops, the journalists could travel around the country and report on the atrocities which were being committed. Stories ready for publication were then taken to the Ugandan border, from where UNOMUR observers brought them to Entebbe, and beyond.[42]

Dallaire had always seen UNOMUR as a support base for his own mission in Rwanda. The mission demonstrated its value when the UN decided on 17 May to reinforce UNAMIR.[43] Finally, the UN tried to make a serious attempt to protect the Rwandan civilians and stop the killings. This meant that thousands of troops, vehicles, supplies, and ammunition had to be flown to Rwanda. Throughout these months UNOMUR coordinated the arrival of the cargo, guided the convoys through the Ugandan hills, and delivered them to the Rwandan border. Furthermore, the UNMOs assembled large trucks capable of carrying armoured personnel carriers, arranged accommodation for arriving troops at the airport and assisted in the evacuation of UNAMIR casualties. The two helicopters UNOMUR had at its disposal were used extensively to transport high-profile individuals, such as representatives from the UN and General Dallaire himself.[44]

The mission officially closed on 21 September, but in reality, UNOMUR’s purpose had ended months before. From June onwards, the mission was being reduced in phases, and the objective of verifying that no military assistance reached Rwanda had become irrelevant. The RPF had started their offensive immediately after the killings in Rwanda started and swiftly conquered the whole country. They unilaterally declared a ceasefire in July and installed an interim government.[45] The observers were monitoring the party that was making an end to the genocide in Rwanda.

Involvement of the Dutch peacekeepers

The observers of UNOMUR became much more involved in the Rwandan conflict than had ever been anticipated. They conducted many more tasks than had originally been foreseen. And whilst the world looked away from the unfolding genocide, they continued their operations. There has been a lot of attention for the failure of UNAMIR and the international community during the Rwandan genocide. But the neglect of the efforts of UNOMUR by historians is fascinating. Given that the Netherlands was one of the main contributors to this mission, the neglect by Dutch historical research is even less understandable. These twenty men, some of whom contributed generously to this research, and UNOMUR as a whole, have been forgotten in Dutch historiography about the episode.

UNOMUR consisted of observers from Bangladesh, Botswana, Brazil, Hungary, the Netherlands, Senegal, Slovakia, and Zimbabwe. There were twenty-two Bangladeshis, four Hungarians, and around ten from each of the other countries. Some stayed for the whole mission, others were replaced midway through.[46] In the case of the Netherlands, the first rotation of ten observers was replaced by a second group in early March 1994. Given what was about to happen in Rwanda, the two groups had completely different experiences.

With Dallaire in Rwanda, the mission was led by an Acting Chief Military Observer, whose main focus was on external relations with the Ugandan authorities or visiting officials. The ACMO had a deputy, who was also the chief of staff, which put him at the centre of internal affairs. For the duration of the mission, the position of deputy was filled by Dutch officers, respectively Lieutenant-Colonel Jan-Cees van Rijckevorsel and Lieutenant-Colonel Leen Noordsij. Furthermore, two Dutch captains served as the mission’s Chief Military Personnel Officer. Together with the deputy CMO, they were responsible for the team allocations and patrol duties, meaning that the Dutch played quite a central role in the mission. The other Dutch were divided between the two sector headquarters, East and West.[47]

Large peacekeeping missions, such as UNAMIR and UNPROFOR, usually consist of infantry units. Military observers, on the other hand, like those of UNOMUR, are deployed on an individual basis and, as rule, are always officers. However, half of the Dutch contingent consisted of Chief Warrant Officers, the first and only time in history that non-commissioned officers have served as UNMOs. The results of this experiment were mixed, or in the words of General Dallaire: ‘The disadvantages overall were more significant than the advantages.’ This was not because of their quality in the field. They were ‘direct and determined’, with operational knowledge and the skills to perform their duties. But the CWOs encountered some problems in the cooperation with other officers. With the exception of a few positions at the mission’s headquarters, most members of the mission were simply classified as an UNMO, in which case a CWO was on an equal footing with an otherwise higher ranking officer. Some officers from other countries, however, were not used to co-operate with CWOs in a military sense, causing some tension affecting the cohesion within the group.[48] The teams of UNOMUR, at observation posts or during patrols, were led by a team leader, usually a high-ranking officer, and a second-in-command. But in teams of five or six UNMOs, many decisions were made by consensus. For officers from countries who are used to a more structured hierarchy, such consultations could sometimes be somewhat uneasy.[49] Ultimately, the use of CWOs in UNOMUR did not seriously affect the effectivity and the outcome of the mission. There were challenges in creating group cohesion, but according to the interviewees, both officers and CWOs, and from different nationalities, it was not the deployment of CWOs that caused this. Rather, they attributed it to the need to co-operate with soldiers from other countries and other cultures, which is a challenge in any multinational mission. Nevertheless, the UN never again used CWOs as military observers.[50]

Like the rest of UNOMUR, the Dutch were affected by the two major events during the mission: the establishment of UNAMIR and the outbreak of the genocide. A few experiences are particularly interesting.

When Dallaire was chosen to lead UNAMIR he was able to bring with him a few officers from UNOMUR to Rwanda. Amongst them was a Dutch captain, who became his adjutant and subsequently spent the rest his deployment at the mission’s headquarters in Kigali.[51] His efforts were apparently satisfactory because when he was relieved in March 1994 he was succeeded by another Dutch captain. The latter, however, would only spend a few weeks in Rwanda. He was in Kigali when President Habyarimana was killed and witnessed the horrifying first few weeks of the genocide. He was then recalled, and joined his fellow countrymen in Uganda, where he stayed until the entire Dutch contingent was sent home.[52]

Operation UNAMIR. Passengers are invited to board a C-130 Hercules. Photo Beeldbank NIMH

They were not the only ones who were deployed outside of the original mission area. When the genocide broke out and most humanitarian organisations were pulling back to Uganda, the airport at Entebbe became a crucial logistical hub. Suddenly Uganda was overflowing with NGOs who were all flying in aid destined for Rwanda. Things got even busier when it was decided to reinforce UNAMIR, which included manpower and vehicles. In order to get a grip on this massive flow of supplies, people, and all sorts of transportation, UNOMUR sent a team to Uganda’s capital, Kampala, and a team to Entebbe. In both cases, a Dutch observer played a central role.

At Entebbe, airplanes continuously arrived with armoured vehicles for UNAMIR. The liaison team arranged the unloading of the vehicles, painted them white, and put them on transport to the border. They set up convoys to deliver all the supplies that were coming in to Kabale, from where the convoys drove on to the border, and into Rwanda. UN troops were arriving and leaving, almost daily, from Entebbe. Therefore, the team arranged a transit camp to accommodate all these soldiers while transport was being arranged. High-ranking individuals also arrived at Entebbe, but they could use the UNOMUR helicopters to travel around.[53]

In Kampala, the liaison team was in charge of the supplies for UNOMUR, which could be water pumps and reserve parts for the helicopters, but also flight tickets for UNMOS who were scheduled to go on leave. In the maze of warehouses, unexpected arrivals of airplanes and improvised convoys, supplies could get lost easily. It was up to the observers to set up a proper supply line to UNOMUR.[54]

The convoys of supplies and reinforcements for UNAMIR, and humanitarian aid, which were supervised and escorted by the observers, came together in Kabale, from where they continued to Rwanda. As mentioned before, UNOMUR and UNHCR arranged meetings, where NGOs could come together, share information, and coordinate operations. Most humanitarian organisations are self-sufficient, but nevertheless, these sessions provided the opportunity to come together and establish the areas where the various NGOs were active. The result was that after a few weeks’ time around sixty representatives from different organisations were attending. And again, it was a Dutch observer who was central to the organisation of these meetings.[55]

All in all, the Dutch contingent played quite a central role in UNOMUR. Not just in the original setup of the mission but particularly in the expanded operations after the genocide, they demonstrated their operational and managerial skills. Unfortunately, they never got much recognition for their work in Uganda when their deployment was over. However, all attention was on the Balkans, and hardly anyone was aware of the fact that Dutch soldiers had also served in Uganda. Some were invited for a debriefing with experts and psychologists. Others never got such a debriefing at all.[56]

Conclusion

Was the possible flow of weapons from Uganda to Rwanda impacted by having eighty-one observers on the border? Considering the means they had to monitor the whole area: probably not. Would NGOs have been unable to deliver humanitarian aid to Rwanda without UNOMUR liaisons at the airport and escorts to the border? Given their experience in delivering aid in conflict areas, that seems unlikely. Was the establishment of UNAMIR only possible because UNOMUR was already on its way? It was perhaps a bit easier, but it was not conditional. And would the UN have been able to properly reinforce UNAMIR without the logistics already set up by the observers in Uganda? Again, their presence probably mitigated things a bit, but the reinforcements would have gotten there either way.

It is perfectly explainable why UNOMUR has received so little attention. It was not the largest mission, nor the most important, and definitely not the most effective. But the context of the mission has to be considered. A genocide was being committed and the international community did not just look away, it actively reduced the peacekeeping mission going on in Rwanda. The observers, however, stayed put, expanded their operations, and tried in every way to assist in the logistical circus unfolding in Uganda.

Considering how much critical attention there is for the efforts of the UN in Rwanda, it is fascinating to realise how little UNOMUR is taken into consideration. To quote General Dallaire: ‘No one has ever asked me a question about UNOMUR.’[57] In order to learn from previous missions and improve peacekeeping efforts, small missions such as UNOMUR, functioning as a deterrent and a support mission, have to be included in the analysis. Besides, considering that the Dutch were among the biggest contributors to the mission, the positions they had in the mission, the roles they took on which had not originally been planned, and the lack of recognition they got back home for their efforts in Uganda, it is a shame that so little has been written about this mission in the Netherlands. Hopefully, this article may serve as a start. And perhaps a lot can be learned if more missions of a smaller nature are analysed. Then, at the very least, the individuals involved can get the recognition they rightfully deserve.

[1] Michael N. Barnett, Eyewitness to a Genocide: The United Nations and Rwanda (Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2012) 1-2.

[2] Arthur Klinghoffer, The International Dimension of Genocide in Rwanda (Basingstoke, Palgrave, 1998) 6.

[3] Alison Des Forges, “Leave None to Tell the Story”: Genocide in Rwanda (New York, Human Rights Watch, 1999) 31-32.

[4] Klinghoffer, The International Dimension of Genocide in Rwanda, 6.

[5] Gérard Prunier, The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide (London, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1998) 47-53.

[6] Scott Straus, Making and Unmaking Nations: War, Leadership, and Genocide in Modern Africa (Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2015) 281-283.

[7] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2020) 161.

[8] Ogenga Otunnu, ‘Rwandese Refugees and Immigrants in Uganda’, in Howard Adelman and Astri Suhrke (eds.), The Path of a Genocide: The Rwanda Crisis from Uganda to Zaire (New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers, 1999) 22.

[9] Prunier, The Rwanda Crisis, 70.

[10] Ibidem, 72-73.

[11] Des Forges, “Leave None to Tell the Story”, 46.

[12] Catharine Watson, Exile from Rwanda: Background to an Invasion (U.S. Committee for Refugees, 1991) 2

[13] Prunier, The Rwanda Crisis, 114-115.

[14] Bruce Jones, ‘The Arusha Peace Process’, in Howard Adelman and Astri Suhrke (eds.), The Path of a Genocide: The Rwanda Crisis from Uganda to Zaire, (New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers, 1999).

[15] Letter dated 28 February 1993 from the permanent representative of Rwanda to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council, S/25355, 3-3-1993; Letter dated 28 February 1993 from the permanent representative of Uganda to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council, S/25356, 3-3-1993.

[16] UN Security Council, Resolution 846, S/RES/846, 22-6-1993.

[17] Roméo Dallaire, Shake Hands With the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda (Cambridge, Da Capo Press, 2003) 46.

[18] Interview with Dutch UNMO-1.

[19] Ibidem.

[20] Interview with Dutch UNMO-2.

[21] Interview with Dutch UNMO-1.

[22] Interview with Roméo Dallaire.

[23] Interviews with an African UNMO.

[24] Interview with a Dutch UNMO-3.

[25] Daily situation report, 27-1-1993. Weekly situation report, 7-6-1994.

[26] Interview with Dutch UNMO-1.

[27] UN Security Council, Resolution 872, S/RES/872, 5-10-1993.

[28] Interview with Dallaire.

[29] Des Forges, “Leave None to Tell the Story”, 149.

[30] UN Security Council, Resolution 912, S/RES/912, 21-4-1994.

[31] Interview with Dutch UNMO-2.

[32] Interview with Dutch UNMO-4.

[33] Dallaire, Shake Hands with the Devil, 409.

[34] Interview with Dutch UNMO-2.

[35] Interview with Dutch UNMO-4.

[36] Interview with an African UNMO.

[37] Interview with Dutch UNMO-4.

[38] Bart Nauta, ‘Zaïre: verhaal van een vergeten missie’, Militaire Spectator 187 (2018) (3).

[39] Interview with Dutch UNMO-3.

[40] Interview with Dutch UNMO-4.

[41] Interview with an African UNMO.

[42] Dallaire, 332.

[43] UN Security Council, Resolution 918, S/RES/918, 17-5-1994.

[44] Interviews with Roméo Dallaire and Dutch UNMOs-2, 4 and 5.

[45] Barnett, Eyewitness to a Genocide, 151.

[46] ‘Facts and Figures’, United Nations Peacekeeping. See: https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/unomurfacts.html.

[47] Interviews with Dutch UNMOs-1, 2 and 4.

[48] Interview with Roméo Dallaire.

[49] Interview with Dutch UNMOs-4 and 5.

[50] Interview with an African UNMO and Dutch UNMOs-2, 3 and 4.

[51] Interview with Dallaire.

[52] Interview with Dutch UNMO-5.

[53] Interview with Dutch UNMO-2.

[54] Interview with Dutch UNMO-3.

[55] Interview with Dutch UNMO-4.

[56] Ibidem.

[57] Interview with Roméo Dallaire.