Ever since Qadhafi was removed from the political arena in 2011 Libya has been in chaos. Libya has seen many governments which were unable to stabilise the oil-rich North African country. The international community appears to be divided over the future of Libya. Most recently heavy clashes have broken out in Tripoli between armed groups of self-proclaimed Field Marshal Haftar and the imposed government under Prime Minister Sarraj. Haftar has been advancing towards Tripoli ever since 2015, initially stabilising and consolidating in Cyrenaica, his power base, then neutralising radical elements in the south of Libya, and ending with the Battle for Tripoli. Entering Tripoli with military force must be assessed as a miscalculation lacking any logic. It is likely that Haftar was lured into the fights by his own hubris, encouraged by foreign supporters.

Col Peter B.M.J. Pijpers*

‘I against my brother. I and my brothers against my cousins; I and my brothers and my cousins against the world.’ - Arab Bedouin proverb

‘All wars should be governed by certain principles, for every war should have a definite object, and be conducted according to the rules of art.’ - Napoleon Bonaparte, Maxim V[1]

Libya is in chaos. Warring factions fight for power in Tripoli, 120,000 people are internally displaced, thousands of refugees fled the United Nations (UN) camps and are on the move, and at least a thousand people were killed in recent months.[2] However, media reports on the situation are contradictory,[3] oversimplified, one-dimensional, and the question comes to mind: ‘who is fighting whom, and why?’

It is not the first time Libya is in a state of war; the current conflict is the third major strife since 2011, the year Qadhafi was removed from office. Ever since the former Libyan leader’s downfall tribe-based strongmen and militias, but also politicians and businessmen, have tried to get ‘a piece of the pie’ and maintain, or, if possible, expand their power. Allegiances in Libya shift frequently in a pragmatic or opportunistic manner, which is so characteristic of Libyan culture. Anecdotal is the support of dairy maker Al Naseem – the King of Yoghurt - to local forces in their fight against the Qadhafi forces in the 2011 civil war.[4] However, Al Naseem’s leadership was not inspired by the greater good of the Libyan people, but forged a pragmatic alliance to further its business interests.

Refugee camp in Libya. The North-African country is in chaos, thousands of refugees fled UN camps. Photo European Commission

Part of the problem might be that there is no overarching record of Libyan statehood. Allegiances in Libya stem from the family or tribe; and Libya is a myriad of cities, families, tribes, religious determinations, political affiliations and ancient feuds long held together by Qadhafi’s ‘divide and rule’ policy and the one communal factor: oil.

The international community is divided on how to assess the current crisis in Libya, let alone on how to solve it. This international fragmentation is based on the same factors that divide Libyan society and hence fuel the conflict, such as politics and religion.[5] But the international community is also divided because its members use the conflict for national interests, ranging from securing a continuous flow of oil, to gaining more prestige within the European Union, to using the Libya file to strengthen their position as a dominant regional actor.[6]

In recent months heavy clashes have broken out between regular and irregular forces affiliated to the Libyan National Army (LNA) of Field Marshal (FM) Haftar[7] and forces linked to the Government of National Accord (GNA), headed by Prime Minister (PM) Sarraj.[8] These clashes, however, should not be taken as mere skirmishes between armed factions, or as an insurgency trying to overthrow the government. The conflict in Libya is a kaleidoscopic overlay of conventional, irregular and information warfare, in which the military instrument of power coalesces with political, economic and societal dynamics.

This raises the question whether the campaign of the apparent aggressor in the current fighting in Tripoli, Haftar, is a deliberate action or a hodgepodge of flukes and coincidences at the whim of actors in neighbouring countries.

The goal of this article is to analyse the most recent crisis in Libya following the LNA campaign to take Tripoli and to assess the strategy behind the LNA campaign and the positions of relevant international stakeholders.

The main question is whether the LNA, up until the Battle for Tripoli which started on 4 April 2019, pursued a more or less coherent objective following military logic. From a military point of view, the Battle for Tripoli itself is ill-focused and lacks purpose and intent. The reason behind this could lay in the fact that taking Tripoli by force was not the initial intent of the LNA, which was lured into it by foreign regional actors whose own national interests prevailed over Libyan goals.

In order to understand the complex Libyan constellation, the article first describes the Libyan societal and political landscape.[9] After that, the military campaign of the LNA towards Tripoli will be analysed in three phases: the operation to secure the homeland lasting until December 2018; the Southern campaign from December 2018 – April 2019; and the Battle for Tripoli starting on 4 April 2019. An assessment will be made whether or not the LNA advance can be labelled as a deliberate military campaign,[10] and what the role of external actors is in the purpose and cause of the conflict. The article concludes with a prudent outlook on the way ahead.

The kaleidoscopic environment

This paragraph distinguishes the layers within Libyan society. The core message is that the various layers are intertwined. Analysing individual persons or groups, including regularly changing allegiances and loyalties never stems from just one perspective such as religion or tribe.[11]

The societal landscape

Libya originates from an old Roman colony centred around Tripoli, which was a pre-Roman ancient city established in the 7th century BC by Phoenicians.[12] Under Italian colonial rule in the early 20th century the three regions, Tripolitania, Fezzan in the south, and the eastern region of Cyrenaica, were united in the Kingdom of Libya.

Map 1 The three regions of Libya

Though a united country on paper, Libya is a constellation of some 140 Arab and non-Arab tribes. The Arab tribes are dominant both in number and in power.[13] The main non-Arab tribes are the Tebu in the south and the Touareg in the southwest of the country, who co-exist without being allies.[14] Qadhafi’s policy of ‘divide-and-rule’ was to provide privileges and domains of power to tribes, if need be also to non-Arab ones, to balance off their differences.

Where religion is concerned, nearly all Libyans are Sunni Muslims.[15] Due to external influences and recent religious exegeses, more radical interpretations of the Muslim scripture and jurisprudence have emerged, such as that of the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafi-Madkhali.[16] Though these interpretations may give rise to radicalism, in general Libyans are not radical in their religious beliefs, causing the failure of the establishment of the Caliphate of ISIL (Daesh) in Libya.

The Libyan economy is founded on oil and gas, administered by the state-owned National Oil Company. Revenues of the crude oil exports are received by the Central Bank of Libya, which manages and allocates the funds, giving it a powerful position. Exponents of the policy of divide-and-rule are the state salaries and subsidies. Libyans hold positions in all state agencies and receive salaries, whereas the actual work is done by other Arab (Egyptian) citizens at managerial level and African and Asian workers at executive level.[17] An important incentive to appease the population is the subsidies on basic goods like olive oil, flour and refined petrol. The system of subsidised goods still exists today, and consumes more than half of the Libyan budget.[18] Subsidised goods, especially refined petrol, combined with the flexible exchange rate of the Libyan Dinar, are the impetus for large-scale corruption undermining the economy.[19]

The political landscape

After its independence in 1951 Libya was an inconspicuous North African country, until the discovery of oil in 1955. By 1959 large concessions were given to Esso, Mobil and other oil companies, after which the king was seen as a marionette providing the national wealth to European powers at bargain prices. Already in 1964, but finally in 1969, King Idris – tired of the constant political feuds - wanted to abdicate. As there was no natural successor, King Idris’ nephew Prince Hassan Rida was to become king on 2 September.[20] A group of young officers, led by Captain Qadhafi, prevented the succession by starting a coup d’etat and on 1 September 1969 the Libyan Republic was born. A period of relative stability commenced.

After Qadhafi’s fall in 2011 a National Transitory Council was formed which ruled until the elections of July 2012, when a new legislative council – the General National Congress (GNC) - was elected to replace it. The GNC had an Islamist agenda propagating a state religion and anti-Western sentiment; it consisted of the so-called revolutionaries,[21] Misratan stakeholders and Berbers. In March 2014 the GNC announced that after the June 2014 elections it would transform into a genuine Parliament: The House of Representatives (HOR).

Map 2 The political landscape of Libya

The GNC, and the government it elected, proved weak and unable to establish stability and security in Tripoli. This not only resulted in the prolonged existence of the armed militias that had been created after the civil war of February 2011, but even empowered these militias by incorporating them into the security structure, with mixed results.[22] The power of the militias, but also the rule of the Islamists in the GNC provoked reactions, most prominently from military commander Khalifa Haftar. Haftar started Operation Dignity in May 2014 to get rid of the Islamist factions in Cyrenaica, mainly Benghazi. Shortly afterwards, troops participating in Operation Dignity even stormed the premises of the government in Tripoli. On top of that, or maybe due to that, the Islamists lost the 2014 elections. Many new lawmakers, now members of the HOR, were moderate federalists, nationalists and secularists – hence favourable to Haftar’s Operation Dignity. To counter Operation Dignity, the Islamists incepted Operation Dawn and, after retaking Tripoli in August 2014, reinstalled the GNC and ousted the HOR, which then settled in Tobruk. From that moment on Libya had two governments: the Islamist GNC in Tripoli, supported by Turkey and Qatar, and the nationalist HOR in Tobruk, endorsed by Egypt and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).[23]

After long negotiations, a UN-brokered political agreement was signed in December 2015 in Skhirat, Morocco, that would herald a new era in Libyan politics.[24] The Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) incorporated both the HOR – as the new Parliament – and the GNC – as the main advisory body.[25] With the LPA a nine-person Presidential Council was set up and the Chairman of that Council, the non-aligned Mr Fayez Al-Sarraj, also became the new Prime Minister of the Government of National Accord (GNA). The LPA and the GNA were unanimously welcomed by the UN Security Council.[26] Unfortunately, the LPA never gained momentum[27] and with the emergence of a new governmental body (the GNA) and the unwillingness of the GNC and the HOR to hand over power, Libya now had three governments.[28]

The real power of the Government of National Accord never extended beyond the metaphorical Naval Harbour in Tripoli, where Sarraj landed on 30 March 2016.[29] Despite some international support from former GNC supporters, the inability to exert power in Libya forced the GNA to turn to the Tripoli armed militias to sustain its powerbase. The Tripoli militias in turn were influenced by Misratan revolutionaries and Islamists which pushed Sarraj into the GNC corner, thereby antagonising the HOR and its proponent Haftar. In 2017/2018 the political landscape therefore veered back to a bipolar system: Sarraj and the Islamists in Tripolitania, and the HOR with Haftar in Cyrenaica.[30]

The military landscape

Libya’s de facto security structure is based on militias without any form of civilian oversight. To make the situation worse, the military and police personnel that were on the pre-2011 payroll still get paid while serving in the militias in the east and west. In effect, both warring factions in the current Battle for Tripoli are being paid by the state.

Libya’s de facto security is based on militias. Photo United Nations

The two main elements of the armed groups are the armies and the Tripoli militias. Both the GNA and the HOR have a nominal army: the Libyan Army versus the Libyan National Army commanded by Haftar.[31] Though Haftar claims to have an Army and Air Force of 100,000 people they are in fact, like the GNA Libyan Army, a conglomerate of loosely affiliated militias.

The most relevant four militias are Tripoli-based, united in the Tripoli Protection Force (TPF) and controlling Tripoli city and the ministries in their territory.[32] Sarraj is dependent on these militias to stay in power. Despite this, the allegiance of the TPF can hardly be called pro-GNA. They are driven by personal, financial or tribal interests and are only unified in their opposition against Haftar. Next to these four militias are other armed groups which often have linkages to adjacent cities, such as Misrata, Tarhuna, and Zintan.[33] Appreciating the Tripoli militia is difficult due to shifting allegiances, including occasional embedding in the Libyan Army and the Libyan National Army.[34]

The international actors

UN Special Envoy and Head of the UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), Ghassan Salamé, presented his Action Plan when taking office in September 2017, which included organising a National Conference, presidential and parliamentary elections and drafting a constitution in order to break the deadlock between PM Sarraj (GNA) and the LNA commander Haftar.[35] Though Sarraj and Haftar regularly met, most notably in Abu Dhabi in February 2019, a political agreement did not solidify, partially because both Sarraj and Haftar backtracked frequently.[36] Haftar became frustrated with Sarraj who, despite the fact that he was Prime Minister, did not have a mandate to negotiate. Even worse, Sarraj had to consult the central militias in Tripoli – not the GNA - before reconvening in the negotiations.

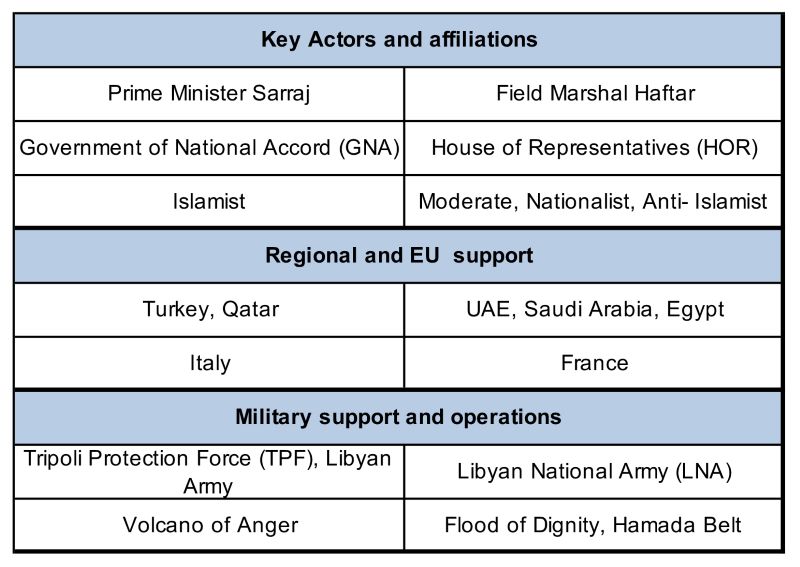

Figure 1 Libyan actors in the March on Tripoli

The role of the international community and the individual countries that have stakes in Libya is dubious since their support is often tacit or covert.[37] In general, Sarraj’s government is supported by countries that have an ideological, religious or economical interest in Tripolitania. Cyrenaica is supported by the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Egypt.[38] The role of both the Russian Federation and the US is ambiguous.[39] In sum, stakeholders are not aligned and have different ideological, religious, financial and petrochemical interests.

The march on Tripoli – Haftar’s campaign for power

Since its inception late 2015, the GNA hardly made any progress. Haftar, on the other hand, has been moving geographically, militarily and politically. Without taking sides in this conflict, the dynamic activities of Haftar are more interesting to analyse vis-a-vis the paralysed position of Sarraj.

The campaign of the LNA towards the current Battle for Tripoli, can be viewed in – or rather reconstructed into - three phases. In each phase the strength of, emphasis on, and coordination between the political, informational, economic and military line of operation changes. Haftar’s Leitmotiv, however, has not. Ever since March 2015 his narrative has been to oust Islamist entities from Libya. The intent of the LNA can be described as stabilising the country, securing the borders and neutralising the extremist entities in Libya, with a special focus on (religiously) radicalised and terrorist cells – including Daesh and Al Qaida.[40] But, did they follow a pre-planned campaign or were they steered by incidents?

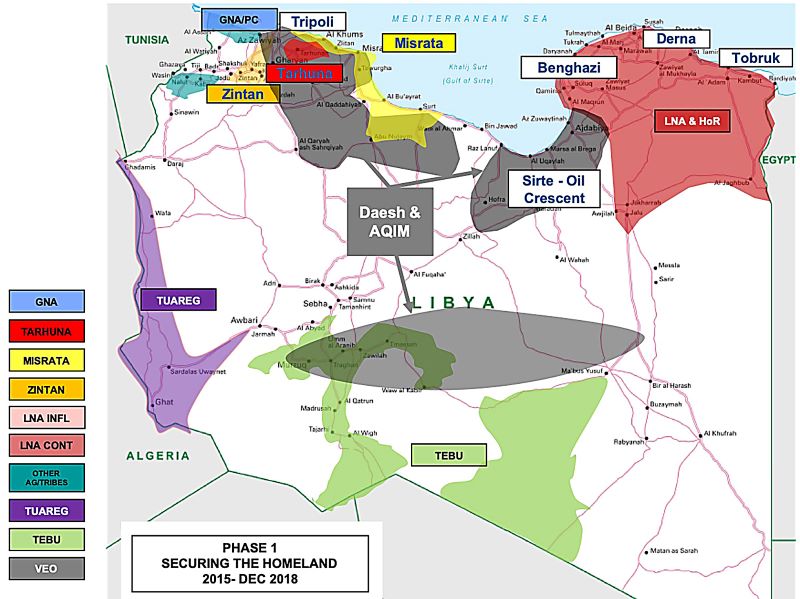

Phase one – securing the homeland

Initially, the main aim of the LNA is to secure and hold northern Cyrenaica. The fighting in this phase lasted until the end of 2018 and entailed protracted urban warfare against Daesh- affiliated cells in Derna and Benghazi. In the timeframe of this phase, Libya had at least three competing governments – affiliated to the GNC, GNA or HOR – and the presence of Daesh was substantial in many parts of Libya, namely in Derna, Benghazi in the northeast, in the Sirte (oil) basin, but also in the south.[41]

During this period Haftar’s campaign was mainly military and, arguably, without political or economic objectives, let alone an all-comprising strategic plan. Political endeavours focussed on political survival, which applied to all three governments.[42] The economy is a problematic factor for all parties in Libya; the oil production decreased due to Daesh’s occupation of the Sirte basin. On the informational and ideological side, the Cyrenaica government, but also the LNA, is closely connected to Egypt, whose main goal is to create a strategic hinterland in Cyrenaica and to neutralise nascent elements of the Muslim Brotherhood. Additional support is provided by the US to combat terrorism and by France to decrease potential spill over to Chad.

Map 3 Phase 1 Securing the homeland

The military endeavours of the LNA may be described as a mix of conventional and irregular warfighting in built-up areas (Derna and Benghazi). In this phase activities to shape and establish the conditions for the upcoming advance commenced, extending to like-minded militias in Tripolitania.

Crucial in this period is the battle for Sirte in the oil crescent. In the Spring of 2015 Daesh captured the Sirte oil crescent resulting in a plunge in oil production. That presented, therefore, an existential threat to the Libyan state. In May 2016 a coalition of forces, mainly Misratan forces and the Petroleum Facility Guard,[43] supported by the US, Italy and the UK, expelled Daesh from the Sirte area.

Significant was the absence of the LNA during this battle, although the clashes occurred near LNA’s area of influence. Haftar exploited the situation and moved in right after the fighting, when foreign entities disengaged and the Misratans and Petroleum Facility Guard were exhausted. After international pressure, Haftar handed the oil crescent over to the National Oil Company, thereby securing Libya’s wealth for all Libyans. In hindsight, Haftar’s action can be seen as successful; firstly, because Daesh was expelled from the oil crescent without any LNA losses; secondly, handing over the oil crescent made sure that the revenues did not only go to Tripolitania; and thirdly, it increased Haftar’s profile and generated the posture of a statesman operating in the interest of all Libyans.

The successful aftermath of the Sirte battle might have sparked Haftar’s appetite to increase his zone of influence and inflated his idea to rule Libya, under the pretext of a nation-wide anti-terrorist narrative. Despite the protracted struggle against pockets of Daesh fighters in Derna and Benghazi, the years 2017/2018 were rather quiet for Cyrenaica, and Haftar could use this period to generate support, refine his influence operation via social media, and plan the next phase in the campaign, which was to be more comprehensive not in the least since Haftar was now in control of all instruments of power in Cyrenaica.

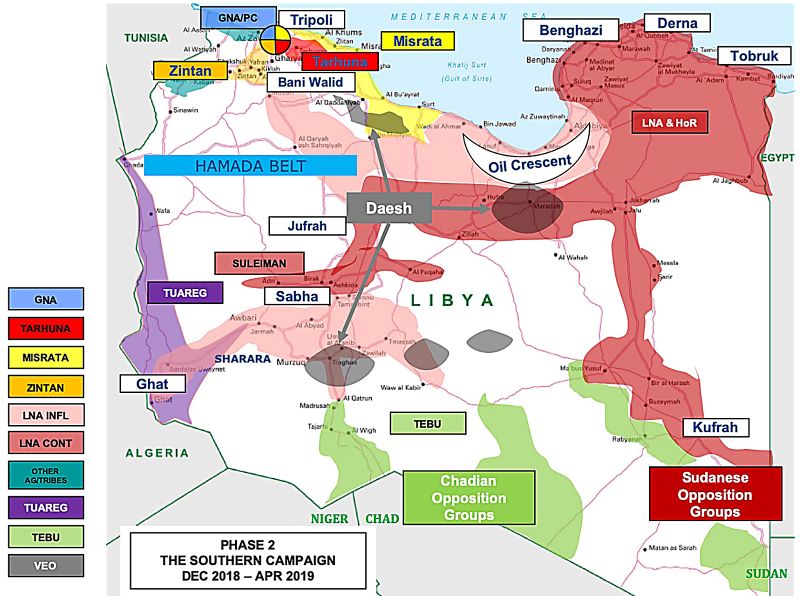

Phase two - the Southern campaign (2018-2019)

The LNA started Operation ‘Anger of Desert’ with the objective to stabilise the Fezzan region and neutralise terrorist elements in the south, arguably, the second phase of the LNA campaign. The start of the operation in early January 2019 was possible following several pragmatic experiences. Firstly, international endorsement of the anti-terrorist narrative could be exploited to increase influence in the south and even in Tripolitania where Daesh had attacked the Ministry of Foreign Affairs late December 2018. Secondly, oil could be used as political leverage. By ousting rogue forces from occupied oilfields, Haftar’s position as politician increased and funds for Cyrenaica were secured. Thirdly, alliances with Tripoli militias might increase the influence of the LNA in Tripolitania but, using the experience of the Sirte plot, would also cause intra-militia clashes after which the exhausted militia would no longer be an obstacle and would facilitate Haftar’s taking of the city without having to fire a shot.

The Southern campaign was an envelopment operation whereby the LNA moved from Cyrenaica towards the southwest, thus protecting their flanks from Chadian and Sudanese rebels (Kufrah). The LNA then moved to the Tebu area and seized the main areas in Fezzan: Sabha, Ghat in the southeast and the Jufra area in central Libya. Haftar also seized strategic infrastructure, the main airports and, first and foremost, the oil facility of El Sharara in the south. On 27 January 2019, Operation Hamada Belt got underway, directing Haftar’s units from the south in northerly direction to Tripoli. In the days after the Abu Dhabi talks, LNA units advanced north to Bani Walid, a strategic position to the south of Tripoli and Misrata in Daesh heartland. Mid-March, the operational headquarters of the LNA was transferred from the south to the northwest, marking the end of the second phase.[44] On 20 March Salamé announced that the National Conference was to be held from 14-16 April in Ghadames. On 2 April, the remaining LNA loyalists took staging areas near Jufrah Airbase.

The LNA gained control over large areas of the country. The operation carefully avoided the Sirte basin, Misrata, and stopped short of Tripoli, in order not to provoke the stakeholder in these regions, and not to lose international support, but also to keep the oil flowing and the door open for a Libyan solution involving the powerful city of Misrata.[45]

On the political front the Southern campaign was a success, even PM Sarraj initially welcomed Haftar’s actions in the south. The Southern campaign strengthened Haftar’s position as an altruistic statesman bringing stability to the south and creating a perfect position to commence negotiations on the future of Libya at the National Conference. But in the light of these seemingly positive developments the Abu Dhabi talks must have been a disillusion to Haftar. Though initially lauded as a success and preluding the National Conference, the fluid agreement that was made evaporated when Sarraj had to consult with his power base, the Tripoli militias.

Map 4 Phase 2: The Southern campaign

Strategic communications changed during the Southern campaign. The initial narrative, to counter and neutralise mainly Islamist radicals, now broadened to terrorists – which would gain Haftar more international support[46] - and the central militias (TPF) in Tripoli. The TPF was becoming a thorn in Haftar’s side since it increasingly took control of Sarraj, which made it impossible to strike a deal to capitalise LNA successes and secure funds for Cyrenaica.[47]

The economy is the Cyrenaican Achilles heel, not in the least since the Central Bank was linked to Tripoli militias and the GNA. The Central Bank started to undermine Cyrenaican banks by withholding money or credit, forcing them to issue bonds based on money printed in Russia that were financially built on air, hence generating huge debts. Money was needed for basic public services, but also for financing the LNA. In contrast to the handing over of the Sirte oil basin in 2016, Haftar appeared reluctant to cede the oil field in the southeast of Libya (El Sharara and El Feet) to the National Oil Company and it may therefore be assumed that some financial arrangement in favour of Cyrenaica had been negotiated.

Militarily speaking the Southern campaign was a sequence of geographical sub-phases with shaping and decisive activities. Shaping activities consisted of building coalitions with local forces based on ideology, a common enemy or bribery.[48] The shaping activities were amplified by a strong influencing campaign using social media, especially Facebook, YouTube and Twitter.[49] Subsequently, the decisive actions merely sufficed as deterrence, thereby avoiding large scale use of force. During this phase the LNA also engaged militias in Tripoli, especially those antagonising the TPF and provoking clashes.

Key tenets during the Southern campaign were speed, the willingness of the population to welcome the LNA and Haftar as liberators, and the positive feedback from the international community. Even the UN complimented Haftar at the end on the campaign in the south.[50] The US and Germany adapted their positions and openly consulted with, or recognised, Haftar. Moreover, the campaign appeared to have been properly coordinated with the political and economic lines of operation. Contrary to the first phase, during the second phase all instruments of power were used in unison. It can be argued that during the second phase Haftar exerted coercive diplomacy in which the military ‘power to hurt’[51] supported the political objective, strengthening Haftar’s position for the upcoming National Conference.

But was that enough? Haftar desperately needed an agreement to solve the financial issues of the east, and a deal on the Central Bank as included in the ill-fated Abu Dhabi talks. Furthermore, Haftar felt strengthened by the success in the south and became reluctant to negotiate with Sarraj, whom he, given the shifting balance of power in Libya, no longer perceived as his peer. Also, Haftar assessed that the population and the UN were on his side and negotiations with Sarraj were merely hurdles withholding him from taking the leadership over the Libyan people. Haftar, at that time, was also increasingly being courted by key leaders in Egypt, the UAE and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, all hinting at or promising financial and military materiel or support. After all, Haftar was 75 years old and under constant medical supervision,[52] so time was not on his side.

All in all, the principles of warfighting were followed in the Southern campaign, there was synergy between the lines of operation, following Western-style doctrine.[53] The Southern campaign can be seen as an envelopment operation towards Tripoli thereby pre-positioning units to the south of Tripoli to pressurize the political process, while in the meantime neutralising terrorists in the Fezzan and avoiding any confrontation with the Misratans to keep the Libyan political solution viable. The question that remains is: ‘Was the Southern campaign an isolated operation to neutralise Daesh elements, or was it indeed a second phase in a larger campaign?’

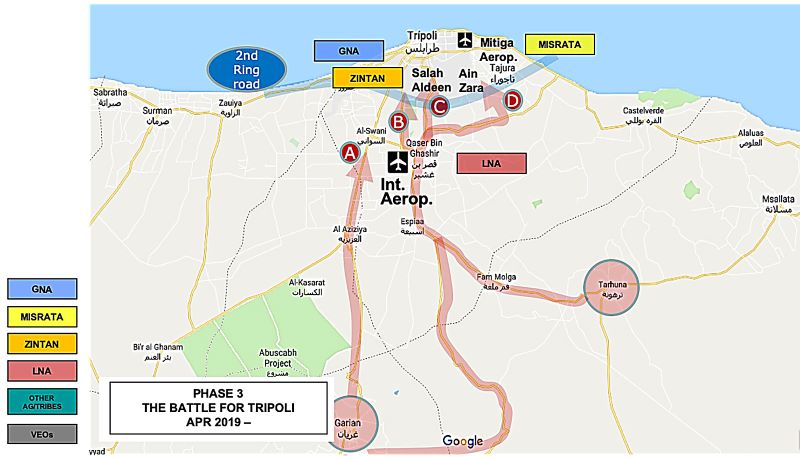

Phase three - the Battle for Tripoli (4 April 2019)

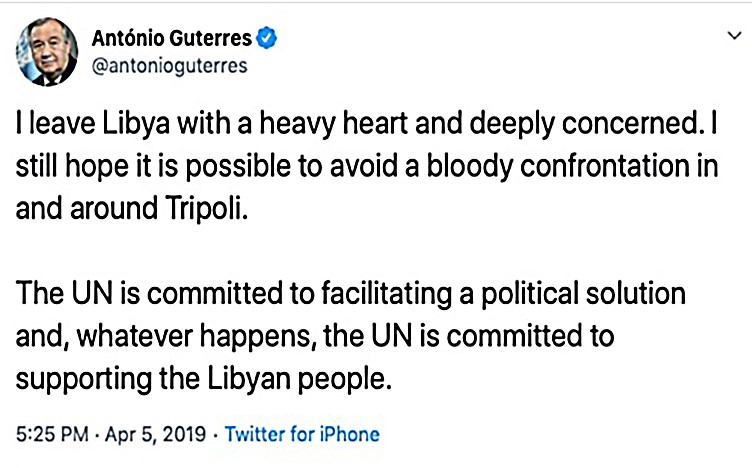

The Battle for Tripoli started with ‘brief skirmishes’[54] between LNA affiliates and GNA entities in the city of Gharyan in the night of 3 to 4 April. Gharyan is near Tripoli but far away from the LNA bases.[55] While the LNA spokesperson, Brigadier Mismari, seized the opportunity and announced that the operation to oust terrorists from Tripolitania had started, UN Secretary General Guterres visited Libya and spoke with Haftar, without much success, though.[56] Haftar’s refusal to budge would set the tone for further UN involvement between the two fighting sides.

Map 5 Phase 3: The Battle for Tripoli

On 5 April, the LNA established four marching routes towards the centre of Tripoli, an operation branded ‘Flood of Dignity’. Two days later, the GNA officially launched a counter-operation called ‘Volcano of Anger’. Salamé had to announce the postponement of the National Conference in the days after. The fighting in the early stages was fierce and included air attacks and intensive influencing campaigns on social media, blaming the opponent for indiscriminate shelling.

After initial LNA success, on 18 April a stalemate occurred with the LNA and the GNA holding opposite positions on the marching routes, around the second ring road. Though the LNA gained air superiority after shooting down one of the last GNA Mirages around 7 May, a growing number of militias positioned themselves against Haftar, and radical elements from Zintan and Misrata joined the front on the GNA side.

Once the LNA had moved into Tripolitania, the situation in the south was back to where it was in the pre-December 2018 situation with the traditional power brokers reassuming their positions. The political gains in the south evaporated.[57]

Figure 2 Tweet by UNSG Guterres after visiting Libya, 5 April 2019

Politically, the start of the Battle for Tripoli – the third phase of the LNA campaign – can be regarded as a miscalculation. Haftar’s earlier position as a credible actor, who would deserve a place in the future of Libya, was totally shattered after the third phase. He was unable to capitalise on the successes in the south and lost popular support. Moreover, the international community, especially France, was forced to distance itself from Haftar, pushing him even further into the arms of conservative forces from Egypt, the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

The military operation shows three types of warfare: small scale close quarter combat on the ground in Tripoli; manoeuvre warfare in the air, with command and control and logistic centres as the main targets; and total war on social media.[58] It is, however, doubtful whether the LNA followed a pre-planned scheme of manoeuvre since there was no clear command and control relationship between the fighting entities and the LNA headquarters, nor was there a link with economic or political objectives.

Going into Tripoli head over heels proved disastrous for the LNA disposition. To recap, by the end of the Southern campaign, the LNA had positions near Daesh hot spots, not at the outskirts of Tripoli; and the location of the logistical hub was at a distance of 650 kilometres from Tripoli. The LNA had spared coastal areas, keeping the door open for a political solution with Misrata and preserved the oil revenues. There were on-going negotiations with the local militias in Tripoli. The recurring strategic narrative in 2018 and early 2019 was that Haftar would not take Tripoli by force. Cyrenaica had a politically strong and, at the same time, an economically weak position, hence it was in desperate need of an agreement. Therefore, all the dynamics allude to the assessment that it is more likely that Haftar initially planned to follow a political, not a military, track in which he could impose his conditions on, and personal role in, the future of Libya.

In sum, it seems unlikely that Haftar and the LNA had planned to move into Tripoli on 4 April in a military fashion. The fighting at Gharyan was not planned; moreover, the units starting the fights were not LNA units, but militias that felt aligned with the LNA. However, in the end Haftar seized the opportunity to take Tripoli, most likely encouraged by neighbouring states.[59]

Appreciation and way ahead

Libya is a country divided along certain lines ranging from geography, history, language, religion and politics, even to its national dish. Though one would be inclined to assume that there is a clear East-West divide in Libya, finding solutions only on this fault line would be a recipe for failure as the societal complexity is more nuanced. Moreover, pragmatic and opportunistic allegiances are built from the bottom up and change kaleidoscopically whenever the tribal, family or personal interests sway.

Top-down foreign support will therefore only exacerbate the situation. Though in recent months a convergence of views has been emanating, the international community is fragmented and the UN Security Council was not even able to adopt a resolution condemning the Battle for Tripoli.[60] Foreign support has shifted overtime, but the growing instability has dissuaded European actors from being further involved in Libya, willingly or only after international pressure,[61] resulting in the increased influence of Egypt and the Gulf states. Moreover, the Battle for Tripoli increased UAE and Saudi Arabia’s engagement to fight Islamists, provoking Qatar and Turkey into entering the ideological and regional strife.[62] Libya now appears to be a proxy of a larger ideological and religious feud among the Gulf states, thereby completely paralysing, or at least overshadowing, the political process in Libya.[63]

No battle plan would have survived such political strife. But in the Libyan case, it is doubtful if there was any plan at all. Though the Southern campaign was a well-executed operation, the overall advance of the LNA towards Tripoli was a march of coincidences, not of premeditation.

By entering Tripoli with military means, Haftar overplayed his hand: the population turned against him; powerful international actors distanced themselves from him; and numerous militias changed allegiances and chose to back the GNA, afraid of yet another Qadhafi-era. Haftar’s miscalculation has shattered any illusion of a coordinated approach, destroyed his political stance, made the economic situation in eastern Libya even more dire, and hence left him with only the military instrument of power. Therefore, taking Tripoli by force does not logically follow from the results of the Southern campaign and a prudent conclusion may therefore be that Haftar was lured into the battle by his own hubris and possibly by foreign encouragement.

Libya is now left with two rival entities that are not in control of the conflict, and neither represents the rich diversity of the Libyan people. Haftar has lost much credit and is left with only one instrument to fight with: an army of loosely affiliated militias. His remaining foreign supporters - that control the struggle - will provide materiel and ammunition but only to further their national interests, which will prolong and intensify the conflict not in the least because there is no comprehensive Libyan plan and thus no end state.

NATO Operation Unified Protector. The only sensible effort the international community could make is to urge all foreign actors to stop interfering in Libya. Photo NATO

Do desperate times need desperate measures? Libya does not require a solution imposed by the international community. The only sensible effort the UN, EU or the African Union could make is to urge all foreign actors to stop interfering in Libya, leash the dogs of war, so authentic Libyan actors imbued with family and tribal loyalties and interests can re-emerge with grassroots political engagements and build pragmatic Libyan-style coalitions, democratic or not.

After years of turmoil Libya does not need another North African sandstorm. A mild wind of change will do. And Haftar and Sarraj? Both have exceeded their sold-by date in the Libyan political arena. It is time to let the true spirit of the King of Yoghurt prosper once more. Hence: the king is dead, long live the king.

* In 2019 Colonel (Royal Netherlands Army) Pijpers was appointed to the EU Liaison and Planning Cell embedded in the EU Delegation to Libya, located in Tunis. From 2015-2018 he was strategic planner at the EU/EEAS in Brussels, also focusing on Northern Africa. The present article is based on his experiences in Tunis and Brussels and numerous discussions with experts in the Libyan arena, and reflects the personal views of the author. The author thanks H.E. Mr Lars Tummers for his comments on an earlier version.

[1] Napoleon Bonaparte, The Officer’s Manual. Napoleon’s Maxims of War (Richmond, West&Johnston, 1862) 16.

[2] UNSMIL, 'United Nations Support Mission in Libya Report of the Secretary-General', vol. S/2019/682 (2019); UNSMIL, 'Remarks of SRSG Ghassan Salamé to the United Nations Security Council on the Situation in Libya, 29 July 2019' (2019) https://unsmil.unmissions.org/remarks-srsg-ghassan-salam%C3%A9-united-nations-security-council-situation-libya-29-july-2019

[3] Nicola Pedde, 'The Gulf and Europe: Libya’s Proxy War Is a Web of Conflicting Narratives', Middle East Eye (2019) https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/gulf-and-europe-libyas-proxy-war-web-conflicting-narratives ; Libya Desk, 'US, Haftar and the Chronic Case of Fake News in Libya' (2019) 1–8, https://www.libyadesk.com/news/what-the-us-really-said-to-haftar.

[4] See: Nick Carey, 'Libya’s Wealthy Use Cash to Take Fight to Gaddafi', Reuters (2011) https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-misrata-businessmen/libyas-wealthy-use-cash-to-take-fight-to-gaddafi-idUSTRE76A3A420110711.

[5] Samuel Ramani, 'Outsiders’ Battle to Rebuild Libya Is Fueling the Civil War There' (2019) https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/22/outsiders-battle-to-rebuild-libya-is-fueling-the-civil-war-there/.

[6] Issandr El Amrani, 'Chaos in Libya: It’s the Oil, Stupid', International Crisisgroup (2015) https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/libya/chaos-libya-it-s-oil-stupid ; Editorial Board, 'France and Italy Should Lead on Libya', Bloomberg (2019); Middle East Monitor, 'Libya Turns into Battleground between France and Italy' (2019) https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190122-libya-turns-into-battleground-between-france-and-italy/; Federica Saini Fasanotti and Ben Fishman, 'How France and Italy’s Rivalry Is Hurting Libya', Foreign Affairs (October 2018) https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/france/2018-10-31/how-france-and-italys-rivalry-hurting-libya ; Kay Westenberger, 'Egypt’s Security Paradox in Libya', E- International Relations (2019) https://www.e-ir.info/2019/04/08/egypts-security-paradox-in-libya/; At the time of writing, Egypt was both the Chair of the African Union and of the League of Arab States, which became instrumental for Egypt’s ambitions in the region.

[7] The official rank of Haftar is that of Lieutenant-General, though he was promoted Field Marshal on 14 September 2016 by the HOR after the capture of the oil facilities near Sirte. Though the legitimacy of the HOR is disputed, for the remainder of the article Haftar’s rank will be that of ‘Field Marshal’.

[8] BBC news, 'Libya Crisis: Clashes Erupt South of Capital Tripoli' (2019) https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-48000672.

[9] For the history of the Libyan people see e.g. John L Wright, Libya: A Modern History (London [etc:] Croom Helm, 1981); or Albert Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples (Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1991).

[10] NATO and Netherlands strategic doctrine will serve as benchmark.

[11] For a comprehensive overview see also: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 'BTI 2018 Country Report - Libya' (2018) 37, https://www.bti-project.org/en/reports/country-reports/detail/itc/lby/ity/2018/itr/mena/.

[12] The name Tripoli, or Tarabulus in Arab, stems from the amalgamation of three cities – or polis – alluding to the Greek-Phoenician rather than Roman origin of the city. The cities are Oea, Sabratha and Leptis Magna.

[13] The largest and most influential tribes are the pre-Arab Amazigh or Berbers, the Beni Hilal and Beni Salim. See: Asharq Al-Awsat and Abdulsattar Hatitah, 'Libyan Tribal Map Network of Loyalties That Will Determine Gaddafi’s Fate', CETRI, (2011) https://www.cetri.be/Libyan-Tribal-Map-Network-of?lang=fr.

[14] Both tribes move freely in neighbouring countries Sudan, Mali, Niger and Algeria due to the lack of physical borders in the south. But, there are ancient feuds related to linkages to Qadhafi and more recently to Daesh. See also: Home Office, 'Country Policy and Information Note Libya: Ethnic Minority Groups' (2019) https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1457764/1226_1550070539_libya-ethnic-groups-cpin-v3-0-february-2019.pdf.

[15] About 97 per cent are Sunni Muslims. In Libya the Maliki led by Grand Mufti Al Ghariani and Ibadi Madhabs are dominant schools.

[16] International Crisis Group, 'Addressing the Rise of Libya’s Madkhali-Salafis. Middle East and North Africa Report N°200 |' (April 2019) https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/200-libyas-madkhali-salafis.pdf.

[17] The Libyan economy under Qadhafi was highly dependent on a foreign workforce. After the fall of Qadhafi and the start of the migration crisis, numerous foreign workers blurred the figures of migrants stuck in Libya. See: Tom Westcott, 'In Libya, Hard Economic Times Force Migrant Workers to Look Elsewhere', The New Humanitarian (2019) https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2019/02/18/libya-hard-economic-times-force-migrant-workers-look-elsewhere ; Amanda Sakuma, 'Damned for Trying', Msnbc (2018) 1–5, http://www.msnbc.com/specials/migrant-crisis/libya.

[18] Aidan Lewis, 'Libyan Oil Revenues up Sharply in 2017, Budget Deficit Halved', Reuters (2018) https://www.reuters.com/article/libya-economy/libyan-oil-revenues-up-sharply-in-2017-budget-deficit-halved-cenbank-idUSL8N1P027T.

[19] Libya produces and exports crude oil but has limited refinery capacity and must import refined petrol. The latter is heavily subsidised and therefore smuggled to neighbouring countries in large quantities. On top of that the difference between the official and the black-market exchange rate can accrue to a nine-fold. Buying dollars or acquiring letters of credit in US dollars from the Central Bank of Libya and then reselling them on the black market can accumulate wealth.

[20] There are numerous versions of the abdication of King Idris. One states that the Libyan ally, the US, thought the Crown Prince incompetent and staged a coup d’etat itself supported by high ranking Libyan officers. A group of young officers (which included Haftar) found out and staged an ad-hoc coup preventing this while getting rid of the King, his incompetent successor, the old military clique and US/CIA involvement.

[21] Those tribes and families that first stood up against the Qadhafi regime on 17 February 2011.

[22] Amnesty International, 'Rule of Law or Rule by Fear?' (2012) https://www.amnesty.nl/content/uploads/2016/12/libya__rule_of_law_or_rule_of_militias_.pdf?x43196%252525252520.

[23] The legality of both GNC and HOR has been questionable as neither is based on a genuine popular vote. In Libya the parliaments (lawmakers) are more powerful than the governments (executives) since the former nominally represent the people in all its diversity. Therefore, it is customary to speak about the HOR rather than the Al Thinni government. The current GNA is a mere government without a Parliament and thus has no basis of popular legitimacy for the Libyans.

[24] 'Libyan Political Agreement', no. December (2015), https://unsmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/Libyan%20Political%20Agreement%20-%20ENG%20.pdf.

[25] The ‘High Council of the State’.

[26] United Nations Security Council, 'Resolution 2259' (2015) https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/un_documents_type/security-council-resolutions/page/2?ctype=Libya&cbtype=libya#038;cbtype=libya.

[27] International Crisis Group, 'The Libyan Political Agreement : Time for a Reset', no. November (2016) https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/libya/libyan-political-agreement-time-reset.

[28] One could even, in an anecdotal fashion, argue that in the heyday of ISIL in Libya (late 2015, 2016) the nascent Caliphate would count as the fourth government in Libya. See also: Mattia Toaldo and Mary Fitzgerald, 'A Quick Guide to Libya’s Main Players', no. December (2016) https://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/Lybias_Main_Players_Dec2016_v2.pdf.

[29] See: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-security-politics-idUSKCN0WW1CG.

[30] Due to the decline of ISIL world-wide the number of ISIL fighters in Libya has also reduced significantly, though pockets of fighters still exist.

[31] From old, the LNA is the official (de jure) armed force of Libya and Haftar was nominated by the (then legitimate) HOR and appointed commander of that official force in March 2015 – before the LPA and the GNA existed. After animosities between the HOR, GNC and later the GNA increased the LNA became affiliated to the East. The West (GNA/GNC) established its own Libyan Army, declaring the LNA a rogue force.

[32] The Tripoli Revolutionaries Brigade (TRB), Abu Salim Deterrence and Rapid Intervention Force, the Nawasi militia (8th Force), and the Bab Tajura Brigade, see also http://www.libya-analysis.com/tripoli-militias-unite-into-tripoli-protection-force and Wolfram Lacher, 'Tripoli’s Militia Cartel', Stiftung Wissenschaft Und Politik, no. 20 (2018) 1–4.

[33] Wolfram Lacher and Alaa Al-Idrissi, 'Capital of Militias: Tripoli’s Armed Groups Capture the Libyan State' (2018) 11. The militias that are linked to Misrata are, for example: the Tajura, the Abu Salim militia and the so-called 301 Brigade. Tarhuna has its 7th Brigade militia in Tripoli and the Zintan its Juweilli brigade. But there are also more ‘neutral’ entities, such as the Special Deterrence Force (SDF aka Rada) that controls the national airport or the Janzour Knight in whose area the UN and EU Libyan satellites are; and some – such as the Al Kikkli militia - are near criminal organisations imposing heavy taxations on their Tripoli area.

[34] The Zintani militia in Tripoli is commanded by General Juweilli who is also the Western Commander of the Libyan Army of the GNA. One can only guess about his subordinate units.

[35] United Nations Security Council, 'Security Council Presidential Statement Endorses New Action Plan to Resume Inclusive, Libyan-Owned Political Process under United Nations Auspices' (2017) https://www.un.org/press/en/2017/sc13020.doc.htm.

[36] Other meetings were the Paris/Versailles meeting (25 July 2017), Palermo meeting (12/13 November 2018) and the mentioned Abu Dhabi meeting (27 February 2019). Elissa Miller, 'One Year Later, the UN Action Plan for Libya Is Dead', Atlantic Council September (2018) https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/one-year-later-the-un-action-plan-for-libya-is-dead; Muriel Asseburg, Wolfram Lacher, and Mareike Transfeld, 'Mission Impossible? UN Mediation in Libya, Syrian and Yemen', no. October (2018) https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/research_papers/2018RP08_Ass_EtAl.pdf.

[37] The international community also carries the burden of the NATO Operation Unified Protector. Libyans are weary of foreign interference, especially non-Arab military interference.

[38] European countries often have an economic or defence-industry interest in Libya (Italy’s link to Tripolitania) or in Libyan supporters (France’s link to the UAE).

[39] One could argue that the US stakes are related to the sustainable flow of oil and stability in the region. Russia has economic and geopolitical but also an ideological interest in undermining Western style democracies (including Libya).

[40] In Benghazi, the troops of Haftar fought against the Shura Benghazi Revolutionary Council. This militia was supported by both the GNC and by Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL/ Daesh), hence establishing the virtual connection between IS, radical Islamists and the GNC.

[41] All maps on the disposition of entities originate from the EULPC and are adjusted by the author for the purpose of this article.

[42] Karim Mezran and Erin A Neale, 'Libya : Permanent Limbo or Refreshed Hope?', Atlantic Council (2018) https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/libya-permanent-limbo-or-refreshed-hope.

[43] In the Libyan Army there is a special division for guarding the oil facilities. Also, the Petroleum Facility Guards consist of local militia. The Sirte basin was controlled by the militia of Ibrahim Jadran.

[44] The forward elements moved to Al Watiyah (southwest of Tripoli) while the main HQ and the logistical hub moved from Tamehint in the south to a staging area on Al Jufrah Air Base near Waddan (southeast of Tripoli).

[45] The LNA did have influence in the area surrounding Sirte and Misrata, not least since the coastal area just below Sirte and Misrata was used as a logistical supply route.

[46] Including support from the US and France in their fight against Chadian rebels.

[47] A narrative later also adopted by LNA allies such as the UAE. See: Al Jazeera, 'Haftar Ally UAE Says "Extremist Militias" Control Libyan Capital' (2019) https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/05/haftar-ally-uae-extremist-militias-control-libyan-capital-190502144943188.html.

[48] The common objectives between the LNA and local militias was sometimes eclectic. The Arab Suleiman tribe has had ancient feuds with the non-Arab Tebu. Tarring the Tebu with the same brush as the Chadian rebels or Daesh and framing them all as ‘terrorists’ or radicals made the LNA alliance with the Suleiman tribe mutually beneficial.

[49] Some 60 per cent of the population had access to internet, and 90 per cent of the internet users have a Facebook account. Though social media is a medium where social barriers – between men and women – vanish, it also amplifies differences between groups and aggravates grievances, creates opposition and tensions. Especially so in Libya, where there hardly is any independent media outlet, maybe save for Al Alwasat and the Libya Herald established by the British journalist Michael Cousins. See also: https://medialandscapes.org/country/libya/media/digital-media ; Inga Kristina Trauthig and Amine Ghoulidi, 'Looking into Libya', Atlantisch Perspectief 43 (2019) (3) 12–15 https://www.atlcom.nl/upload/AP_3_2019_Trauthig_and_Ghoulidi.pdf.

[50] Initially Salamé criticised Haftar for violating the international humanitarian and international human rights law, but stood alone in that position. Salamé lost credit due to this incident making him the embodiment of foreign interference in Libyan affairs. Meanwhile it lifted Haftar’s position, but also made the UN competitor, the African Union, a more credible actor, and many countries changed their positions towards Libya, started to recognise Haftar and argued that he should play a role in the future Libyan constellation. These statements undermine the position of UNSMIL since the UN Security Council has stated in all its resolutions that only the GNA is the sole legitimate government in Libya. See for example resolution 2292 (2016).

[51] Thomas C Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven SE, Yale University Press, 1966) 6.

[52] See: https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2018/04/14/le-marechal-haftar-homme-fort-de-la-libye-hospitalise-a-paris_5285345_3210.html.

[53] Though impossible to confirm, it is plausible that Haftar’s Southern campaign has been guided or supported by French and Russian military advisors, leading to a proper and well-considered endeavour. See also: The Jordan Times, 'Libyans Charge France with Double Dealing over Haftar' (2019) http://jordantimes.com/news/region/libyans-charge-france-double-dealing-over-haftar ; and TRT World, 'Russia’s Growing Intervention in Libyan Civil War' (2019) https://www.trtworld.com/africa/russia-s-growing-intervention-in-libyan-civil-war-24751.

[54] According to the LNA spokesperson BG Mismari, see: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/04/libyan-strongman-khalifa-haftar-orders-forces-advance-west-190403155045917.html.

[55] The LNA advance HQ at Al Watiya is 180 kilometres southwest and the main hub at Al Jufrah Airbase is some 650 kilometres to the south of Tripoli.

[56] See: https://twitter.com/antonioguterres/status/1114187435460767744.

[57] Without stating that the Fezzan region has become less secure or stable.

[58] Centro Studi Internazionali, 'Information Warfare in Libya: The Online Advance of Khalifa Haftar', Social Strategic Studies (2019).

[59] What could have happened is that Haftar obtained the green light from one or several of his neighbouring allies to act. This green (or orange) light was not in the best interests of Libya, however, but with the interests of that foreign supporter in mind. See also: Mustafa Fetouri, 'Haftar Has Clearly Been given the Green Light to Conquer Tripoli', MEMO (2019) https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190418-haftar-has-clearly-been-given-the-green-light-to-conquer-tripoli/.

[60]Hayley Halpin, 'UN Security Council Fails to Condemn Fatal Attack on Libya Migrant Centre', Thejournal.ie (2019) https://www.thejournal.ie/un-condemn-fail-libya-attack-migrant-centre-4709528-Jul2019/; The Libyan Express, 'Security Council Fails Again to Condemn Haftar’s Attack on Tripoli, Calls for Ceasefire' (2019) https://www.libyanexpress.com/security-council-fails-again-to-condemn-haftars-attack-on-tripoli-calls-for-ceasefire/; Patrick Wintour, 'Germany Plans Libya Conference to Shore up Arms Embargo', The Guardian (2019) https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/13/germany-plans-libya-conference-to-shore-up-arms-embargo.

[61] Which does not mean that the EU position on Libya is aligned. See: https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-libya-security-eu/france-blocks-eu-call-to-stop-haftars-offensive-in-libya-idUKKCN1RM2WN.

[62] See also: Robert Malley, 'The Unwanted Wars: Why the Middle East Is More Combustible Than Ever', Foreign Affairs, no. November (2019).

[63] Bertelsmann Stiftung, 'BTI 2018 Country Report - Libya'. The GNA can rely on funds and materiel from Turkey, Qatar and to some extent Iran. The LNA gets support from the UAE, Egypt and Saudi Arabia and, to some extent, the Russian Federation; Trauthig and Ghoulidi, 'Looking into Libya’, 13-14; UN News, 'Libya Facing "Serious Crisis" Fueled by Outsiders Bent on Dividing the County' (2019) 1–2, https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/09/1047592.