‘NATO’s mission is to preserve the peace. Not to provoke a conflict, but to prevent a conflict. To do so, we provide credible deterrence’.[1] This is what NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said at the closure of exercise Trident Juncture 2018, one of the biggest NATO exercises after the end of the Cold War. This quote may look or sound familiar. Nonetheless there are good reasons to have a closer look at NATO’s deterrence, as it has regained attention over the last few years. It brings back memories of the Cold War, but in the post-Cold War period deterrence has not had sufficient attention. Nowadays it is back on the radar as is testified by the decision taken at the Defence Ministerial Conference in June 2020 to strengthen NATO’s deterrence.[2] Deputy Secretary-General Mircea Joane stated this new (deterrence) concept would be a comprehensive document which contents are to be embodied in NATO’s operational activities.[3] This article elaborates on the good reasons for doing just that.

Major General C.J. Matthijssen MSS*

A Dutch soldier of the eFP battlegroup in Lithuania. Together with battlegroups in Poland, Latvia and Estonia, it demonstrates NATO’s commitment to collective defence. Photo NATO

This article discusses NATO’s renewed emphasis on deterrence and explores the challenges that come with it. First, the question of what deterrence actually means is addressed, followed by a brief look into the past on what deterrence policy NATO used in the days of the Cold War. Next, the aftermath of the Cold War, the changes for NATO and the implications for deterrence are discussed, before getting to the current situation with the renewed emphasis. That will also include a closer look at the changes in the operational and strategic environment that have (intentionally and unintentionally) paved the way to where we are now. Ultimately, questions such as ‘So what?’ and ‘Now what?’, bringing the challenges and key points of importance to the fore, will receive proper attention at the end of the article.

Some theory

Before diving deeper into this topic, it would be appropriate to start with a few explanatory remarks. Although it is not the intention of this article to elaborate on theory, it may be necessary to point at some theoretical aspects to provide a point of reference for better understanding. That the theory is not so complicated is borne out by Dr. Kęstutis Paulauskas, member of NATO’s Defence Policy and Planning Division, who wrote in 2016: ‘Deterrence is a relatively simple idea: one actor persuades another actor — a would-be aggressor — that an aggression would incur a cost, possibly in the form of unacceptable damage, which would far outweigh any potential gain, material or political.’[4] This indeed sounds very simple. If the threat of severe penalties, such as nuclear escalation or severe economic sanctions, is used, it is called deterrence by punishment. The focus of deterrence by punishment is not the direct defence of the contested commitment but rather threats of wider punishment that would raise the cost of an attack.[5] But this is not the only approach to deterrence. Another strategy is deterrence by denial. This seeks to deter action by making it unfeasible or unlikely to succeed, thus denying a potential aggressor confidence in attaining his objectives.[6]

Both approaches in general give a better view of what deterrence is. Related to the military domain it always involves the use or potential use of military force. This could be either to have military capabilities in place in order to be ready to act upon (punish) the aggressor’s action or to raise the threshold for the aggressor. In short, one could say that deterrence is dissuasion by means of threat.[7] It is a way of affecting the aggressor’s calculus of the risk and cost by threatening either the potential success or the interests of the aggressor.[8] It is worthwhile mentioning that, arguably, there is a slight nuance between dissuasion and deterrence. Dissuasion encompasses a more comprehensive approach than deterrence in its narrower sense, which is primarily about threats.[9] This nuance is not just semantic in the perspective of the hybrid context that will be discussed later.

Deterrence during the Cold War

During the Cold War deterrence, especially nuclear deterrence, was at the heart of NATO’s policy and strategy.[10] This was understandable against the background of the Cold War, as the Warsaw Pact could be considered an existential threat to NATO and its members. NATO was trying to balance its efforts with conventional forces, but ultimately the use of nuclear force could not be excluded. Deterrence by punishment was based on the notion of ‘unactable damages’, including through massive nuclear retaliation for any Soviet attack — conventional or nuclear.[11] On the other hand, deterrence by denial at that time was about making it physically difficult for the aggressor to achieve its objective through forward defence at NATO’s eastern border with the Soviet Union.[12] The United States, but also other countries including the Netherlands, had forces stationed in Germany on a permanent basis. Furthermore, regular major exercises, mainly in Germany, demonstrated NATO’s readiness and willingness to indeed be able to respond to any (potential) Soviet Union act of aggression.

The aftermath of the Cold War

The fall of the Berlin Wall led to the reunification of Germany in 1990 and the withdrawal of East Germany from the Warsaw Pact. Related developments in other Eastern European countries, members of the Warsaw Pact, led to the end of the Pact in 1991. As a result, NATO entered a new era. The organisation and its member states all had to find a new post-Cold War focus. A first sign of this was declared in 1990 at the NATO London Summit. The Summit Declaration stated that ‘Europe has entered a new, promising era [...]. As Soviet troops leave Eastern Europe and a treaty limiting conventional armed forces is implemented, the Alliance’s integrated force structure and its strategy will change fundamentally [...].’[13] The idea of world peace seemed to loom on the horizon. NATO’s main task, the defence of the Euro-Atlantic area, suddenly seemed less evident. Many western nations, including NATO member states, drastically reduced their Defence budgets accordingly. NATO’s second main task, crisis management, came to the front. With Yugoslavia falling apart and subsequently the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina in the early 90s, NATO was on the brink of its next challenge. In 2003 Afghanistan came to the heart of NATO’s focus with the Alliance taking the lead responsibility for the UN-mandated International Security and Assistance Force (ISAF). Meanwhile developments entering the ‘new, promising era’ continued and NATO allies stated in their Declaration at the Lisbon Summit in 2010 that they ‘want to see a true strategic partnership between NATO and Russia, and we will act accordingly, with the expectation of reciprocity from Russia.[14] Throughout these years the Alliance’s know-how of deterrence, including planning, exercises, messaging and decision-making was not at the centre of NATO’s attention.[15]

An armoured battalion manoeuvres through the rough Norwegian landscapes. The 1990 NATO Summit Declaration (London) stated that ‘Europe has entered a new, promising era’. Photo NATO

Unfortunately, things were about to change a few years later. In 2013 the Head of the State Duma’s Defence Committee, Vladimir Komoedov, was quoted in RIA Novosti, a Russian state-controlled domestic news agency, explaining that Russia intended to increase its defence spending significantly, to boost annual defence spending by a further 59 percent to almost 3 trillion rubles ($97 billion) in 2015, up from $61 billion in 2012.[16] Furthermore, in February 2013 General Valery Gerasimov — Russia’s Chief of the General Staff, comparable to the U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — published his article ‘The Value of Science Is in the Foresight’ in the weekly Russian trade paper Military-Industrial Kurier.[17] At that time it did not draw that much attention in the West, but that changed in a year’s time. In 2014 a more dramatic event occurred, namely Russia’s annexation of Crimea. This was a real game-changer. Jonathan Marcus, BBC diplomatic correspondent in Brussels, caught the atmosphere in Brussels in one sentence: ‘Nobody here at the alliance’s headquarters in Brussels is happy about the Ukrainian drama, but through his seizure of Crimea Russia’s President Vladimir Putin may have given a new sense of purpose to the world’s oldest and most successful military alliance.’[18] With that it became clear that this ‘new, promising era’ was not that promising after all. It appeared to be just the beginning of another new era that bore some similarities with the Cold War. The word ‘some’ is explicitly used here because there are significant differences, too. A further brief reference will be made to this later in this article after a discussion of the strategic environment. Anyway, one apparent conclusion can be drawn here: that a ‘true strategic partnership’ with Russia seemed no longer realistic.

Deterrence, it seemed, was about to come back. In September 2014 NATO members gathered for the Wales Summit to discuss the implications of Russia’s game changing annexation of Crimea. In this Summit NATO decided upon a Readiness Action Plan (RAP). This plan provided a comprehensive package of measures addressing both the continuing need for assurance of the Allies and the adaptation of the Alliance’s military strategic posture.[19] The package included, amongst other things, the establishment of the Very High Readiness Joint Taskforce (VJTF), enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) in the Baltics, enhancement of advanced planning, stepping up the exercise program, establishment of NATO Force Integration Units (NFIU) and enhancing Standing Naval capabilities. The assurance measures include continuous air, land, and maritime presence and meaningful military activity in the eastern part of the Alliance, both on a rotational and a permanent basis. The Summit declaration stated that these measures ‘...will provide the fundamental baseline requirement for assurance and deterrence.’[20]

Changes in the security environment

With deterrence back on the radar it is worthwhile to look at the strategic changes that have affected the security environment in the last few decades, thereby focussing on three major changes namely, technological, military operational and geopolitical, because, evidently, these are the main drivers behind a lot of developments in the security arena. This will provide insights in order to conclude whether present-day deterrence is of a different nature than that at the time of the Cold War and where the real challenges lie.

A first important factor of change is technology. New technological developments in the world are significant in terms of speed and contents. Their implications affect the whole of society and their effects are visible in our daily lives, in the industrial, economic and military domain. In the latter, technology enables better precision, increased effective range and higher velocity of weapons. Especially the development of hypersonic weapons has been a rapid process, which is worrisome to some extent. The most obvious effects of technology are the digital communication means that have become part of our way of life. Nowadays about 60 per cent of the world’s population uses the internet and about 3.8 billion people are active on social media.[21] Especially the information domain faces the implications of that and digital communication means have also changed the security environment drastically. The world has become more interconnected than ever. Furthermore, the speed of interaction has grown exponentially. A world leader’s tweet can have strategic effects on the other side of the world in mere seconds. Wars and military operations have shown that the use of the information domain is currently part of warfare. Nowadays there is not only war on the ground; there is also a war of perceptions being fought in the information domain, as was the case, for instance, in Iraq and Afghanistan, but also in the lingering conflict between Israel and Hezbollah. Worldwide terrorist and/or radical groups also exploit the internet and social media to spread their ideological ideas and to recruit.[22] All this underpins the need to explicitly plan the use of the information domain as a natural habit in whatever conflict we operate in. A complicating factor for the Western nations and NATO is that they (choose to) adhere to their values, standards and even more their national and international laws, whilst opponents, whether state or non-state actors, do not always adhere to the same standards or laws. Finally, the validity of news is questioned more and more. An example of this is the mutual accusations of fake news that are uttered every now and then between Russia and the US. The challenge is attributing the source of fake news to either of the two. It is known that it does happen, in some cases because facts provide proof for it, or sometimes former trolls publicly admit to having spread fake news. The Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service in its 2020 report states that ‘Internet trolling is part of Russian intelligence services’ everyday activities.’[23]

The most obvious effects of technology are the digital communication means that have become part of our way of life. Photo Forsvaret, Tore Ellingsen

Technological developments also provided many more opportunities for using the digital domain. An increasing number of Western societies largely depend on digital systems and structures. Public transport, airports, harbours, logistics, healthcare, and infrastructure are just a few vital areas that almost completely rely on digital systems that significantly increase effectiveness and efficiency. But the flipside is that these developments have also brought new vulnerabilities and risks, which created the need to ensure sufficient protection against digital threats. Against this background NATO has adopted Cyber as a separate domain of operations at the Warsaw Summit in 2016.[24] The emergence of the cyber and the information sphere through technological developments exposes the need to include both domains in the scope of deterrence and further expand the deterrence toolbox to be able to cope with the challenges they entail.

The second factor of change, from a military operational perspective, applies to the time between the fall of the Berlin Wall and 2014. In that period the three major arenas of military operations were Bosnia-Herzegovina, Iraq and Afghanistan, involving many Western nations. NATO was committed to crisis management with a major effort, initially in Bosnia-Herzegovina and later in Afghanistan. Meanwhile Russia developed its thinking on how to protect its interests and how to deal with NATO’s expansion to the East. David Kilcullen, in his most recent book The Dragons and the Snakes[25] points at the fact that while the West was fighting snakes (e.g. Global War on Terror, Afghanistan), Russia (and other so-called dragons like China, Iran and North-Korea) closely observed the challenges the West was facing and how asymmetric types of tactics adopted by ‘snakes’ were successfully used in fighting the West (including the use of modern technologies). Basically, as Kilcullen put it: ‘It’s about how state adversaries learned to fight the West by watching us struggle after 9/11, recovered from their eclipse after the Cold War, and transformed (and are continuing to transform) the global threat environment in the process. State adversaries exploited the explosion of new, mostly Western-designed consumer technologies around the turn of this century, took advantage of our tunnel vision on terrorism, and blindsided us with new subversive, hybrid and clandestine techniques of war […..], creating boomerang effects that blurred traditional distinctions between domestic and international space, crime and conflict, peace and war, policing and military operations and reality and fake news.[26] This conclusion may well be justified.

The Gerasimov doctrine, as previously mentioned, made public for the first time in 2013, basically included much of what Russia has observed in terms of asymmetric tactics used by snakes, but also included a comprehensive (whole of government) approach, comprising non-military means. Gerasimov took tactics developed by the Soviets, blended them with strategic military thinking about total war, and laid out a new theory of modern warfare — one that looks more like hacking an enemy’s society than attacking it head-on. He wrote: ‘The very “rules of war” have changed. The role of non-military means to achieve political and strategic goals has grown, and, in many cases, they have exceeded the power of weapons in their effectiveness. […] All this is supplemented by military means of a concealed character.’[27] Reading this carefully also identifies the point that the military instrument of power is probably not even the most important in achieving strategic and political goals. It may even have a more supporting or enabling role amongst other instruments of power. At the Russian Ministry of Defence’s third Moscow Conference on International Security, on 23 May 2014, Gerasimov showed a graphic that illustrated that war is conducted by non-military and military measures in a ratio of roughly 4:1. These non-military measures include economic sanctions, disruption of diplomatic ties, and political and diplomatic pressure. The important point is that while the West considers these non-military measures as ways of avoiding war, Russia, on the other hand, considers these measures as war.[28] It is worth noting that, according to its National Security Strategy, Russia considers the expansion of NATO and the alliance’s approach to Russia’s borders a threat to the country’s national security.[29] Using military and non-military means provides Russia with a variety of instruments to continuously try to divide and weaken NATO. This urges NATO to have a comprehensive view on deterrence, looking at all instruments of power. Furthermore, the developments in the military operational domain call for adaptive and flexible deterrence.

A third element of change lies at the geopolitical level. The more or less clear bipolar world of the Cold War era has disappeared. In today’s more multipolar world the traditional balance of power is clearly shifting. Partly driven by economic developments the world is changing fundamentally, not only Russia under Putin, but also China is more and more assertive in the international arena. Their military modernisation and global economic activities are illustrative of this development. Russia and China are expanding their involvement for their own self-interest. The Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service states in its 2020 report: ‘In recent years, Russia has also begun to shift its foreign policy attention to regions further away in an attempt to establish its position as a major global power.’[30] An example of this is Russia supporting the Assad regime in Syria, which further complicated an already complex situation in the Middle East. Another example are Russia’s efforts in Africa, of which is said that ‘these are efforts to dilute the influence of the United States and its allies in international bodies.’[31] Furthermore, national and regional stability are not self-evident anymore. Arguably, ideological tensions are increasing rather than decreasing. Terrorist types of organisations pose a threat to states and societies, even within national borders, and so the difference between external and internal threats has become blurred.

Five ships line up alongside each other during NATO exercise BALTOPS 2020. Russia continuously tries to divide and weaken NATO, urging the Alliance to have a comprehensive view on deterrence. Photo NATO

Changes in the geopolitical domain further complicate the context for deterrence. On the one hand, the growing assertiveness of countries like Russia and China, but also Turkey and India, presents the risk of increasing tensions, but also the risk that nations seek opportunistic ways of playing a visible role in regional or even global politics. Russia’s and Turkey’s involvement in Syria illustrates this. On the other hand, it leads to the fact that the US hegemony in the world declines, with its implications for NATO as well.

Deterrence in practice

These three major changes, technological, military operational, and geopolitical, provide a perspective on the current security environment and the challenges related to NATO’s deterrence. Earlier in this article, where the theory of deterrence was briefly discussed, Dr. Paulauskas was quoted, saying: ‘Deterrence is a relatively simple idea.’ He may be right concerning the theory, but when it comes to practicalities in the context of the above-mentioned complex environment, it does get complicated and challenges present themselves. In 2016 Professor Wyn Bowen, Head of the School of Security Studies, King’s College London, who has done research on NATO’s deterrence, pointed to these challenges in an article on Defence-in-Depth, the research blog of the Defence Studies Department.[32] Some of these challenges will be referred to later on. But first it is important to realise that NATO is fully aware of the challenges as indicated by SACEUR in February 2018. General Scaparotti, SACEUR at that time, then stated: ‘We now have to manage crises, stabilize, and defend in an environment shaped, manipulated and stressed by strategic challenges. The two principal challenges NATO faces are Russia and violent extremism. Both have strategic destabilization efforts that go after the foundation of our security and target its key institutions. They attempt to turn the strengths of democracy into weaknesses.’[33] Finding the right approach and balance in the strategy is an additional complicating factor. Every situation is different, depending on the interests at stake, the situation itself, the instruments to use, and dilemmas such as de-escalating or (consciously) escalating the situation. That is basically why there is a need to make sure that NATO applies a deterrence policy that aims at credibility and effectiveness. As NATO states on its website: ‘Today, the security environment is more complex and demanding than at any time since the end of the Cold War, reinforcing the need for NATO to ensure that its deterrence and defence posture is credible and effective.’[34]

With this complicated practical reality of deterrence in mind, it should be recognized there are two key factors that are important in making NATO’s deterrence and defence posture credible and effective, namely understanding and alignment.

Understanding

The first factor of importance is to make sure there is a proper understanding of the threat and/or the situation. Planning for deterrence is not very different from planning for defence. It starts with an in-depth analysis of the threat and the environment to get to the right situational awareness and situational understanding. That is a fundamental building block. Russia’s behaviour is based on strategic objectives. For Russia, great power status, regional hegemony, national sovereignty and regime survival may well be the most important strategic objectives.[35] Those objectives will drive its behaviour and activities. The Gerasimov doctrine provides an insight into methodologies how Russia preserves its strategic objectives. The present-day hybrid threat is challenging as hybrid threats are diverse and ever-changing, and the tools used range from fake social media profiles to sophisticated cyber-attacks, all the way to the overt use of military force and everything in between. Hybrid influencing tools can be employed individually or in combination, depending on the nature of the target and the desired outcome. This may include prioritizing prevention of the largest threats to national and Euro-Atlantic security by building a coherent deterrence posture, while, on the other hand, not underestimating the long-term effect of lower level threats that have a corrosive impact on institutions, societies and decision making.[36] The complexity of this situation is one of the main significant differences compared to the Cold War era. As a necessary consequence, countering hybrid threats must be an equally dynamic and adaptive activity, striving to keep abreast of variations of hybrid influencing and to predict where the emphasis will be next and what new tools may be employed.[37] That is why this hybrid context requires a comprehensive and in-depth analysis. This will provide the building blocks to draft deterrence planning. The instruments of deterrence should be adjusted to the desired effects, which can only be achieved with the right understanding as a starting point. But assessing potential second and third order effects is an essential element, too. Those should not be underestimated as they may undermine the required effectiveness. Veebel and Ploom argue in the Lithuanian Annual Strategic Review (December 2018): ‘To answer the question of what should be done in the future to actually deter Russia and to avoid aggression from the Russian side, the essence of the potential conflict should first be discussed. It is argued […] that the more precise the aim against whom, what, and when the deterrence is needed, the more cost-efficient the deterrence is.’[38] But there is more. In-depth understanding requires the ability to sense what drives the opponent’s thinking, which is one of the other challenges Bowen identified. He said: ‘To effectively deter requires getting inside the head of any actor that is the target of deterrence, in any given context.’[39] That could not only be helpful to anticipate developments and/or assess potential reaction, but also to get the best possible idea of how deterrent actions might be perceived by the other side. Certain types of activities may seem to successfully deter the opponent, but if they are perceived otherwise, deterrence has failed.

Alignment

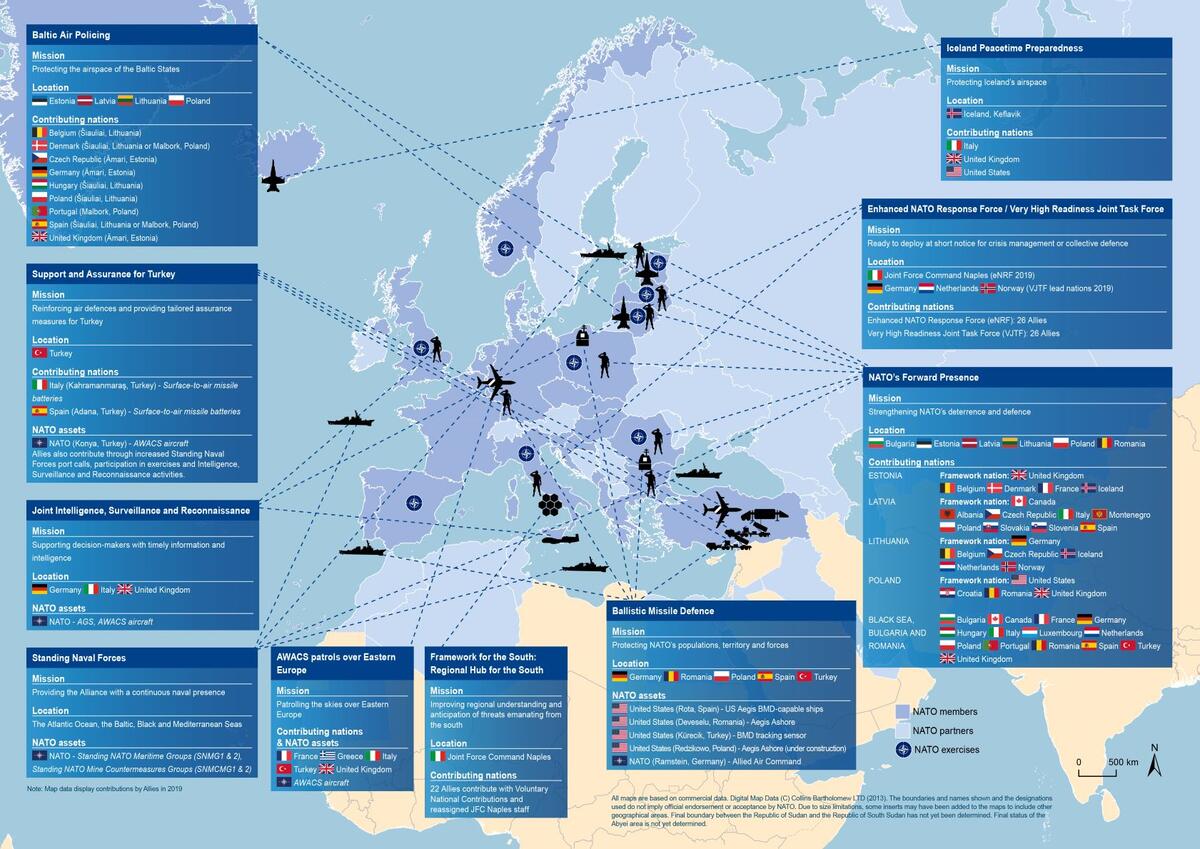

The importance of the second factor, alignment, was referred to publicly in a press conference after NATO’s Chiefs of Defence meeting in May 2020 by the Chairman of the NATO Military Committee, Air Chief Marshal Sir Stuart Peach. Reporting on the refinement of the Concept for Deterrence and Defence of the Euro-Atlantic Area, Peach mentioned one of the aims, being to ‘...improve the future alignment of existing mechanisms, processes and activities as well as the procurements requirements resulting from our continuous process of adaptation. It brings coherence to all our military activities’.[40] The schematic overview in Figure 1[41] shows various elements of NATO’s deterrence and defence. It is quite impressive, but not exhaustive; there is more, such as exercises, strategic messaging and plans. It should be noted that behind every one of those elements there are huge efforts ongoing on a daily basis to plan, refine, prepare, execute and assess activities and their alignment.

Figure 1 Elements of NATO’s deterrence and defence

However, alignment has multiple dimensions. In the military operational domain, there needs to be alignment in the sense of coordination and synchronization of functions that normally apply to military operations like intelligence, manoeuvre, protection, sustainment, strategic communication. That is crucial in achieving the desired effects. But NATO’s deterrence starts with alignment in political decision-making. This is a challenge for an organisation consisting of 30 member states that needs consensus in its decision-making. Bowen pointed at this challenge by comparing Russia’s and NATO’s unity of effort. Whilst Russia under President Putin is able to coordinate all levers of national power and influence in pursuit of its goals, the challenge for NATO involves a 30-member, consensus-based organisation with multiple perspectives and interests seeking to deter […] all its levers of power in a coherent and effective way.[42] A fair point, but in my view NATO’s approval of the Concept for Deterrence and Defence of the Euro-Atlantic Area, as was mentioned before, is an achievement that has shown that NATO is able to meet this challenge.

Alignment also requires a comprehensive perspective. It is not about functions and force in itself. It is also about willingness and ability to deploy and employ force. Readiness, posture and supporting enablement play an important role as well. Infrastructure, as an example, should enable the rapid and smooth deployment of forces, as expressed by Commander Joint Force Command Brunssum (JFCBS), General Vollmer.[43] That also relates to another element of alignment, which is alignment between all stakeholders, being not only NATO entities but also its member states. Nations bear their own responsibilities and they have their national plans. It is part of NATO’s responsibility to take these into account and align them more with NATO activities and plans that aim at deterrence effects. This in itself is an important reason to fully include nations in the implementation of deterrence.

I strongly believe that consensus on the concept is a very good starting point. Operationalising the concept will need to be a collaborative effort involving all the stakeholders that have just been mentioned. The process itself, in which all perspectives should and will be taken into account, will be most valuable and can surely be made to work. Within the military executive domain that always happens because of its ability to find solutions to overcome challenges, as was the case in Afghanistan where at the peak of the ISAF mission about 50 nations, both NATO and non-NATO members, contributed. That was a significant achievement that is often underestimated. In this regard one should not underrate the value of the multinational composition of NATO Headquarters facilitating the exchange of various perspectives on a daily basis. The various national flags shown in Figure 1 are a telling representation of the various nations involved in each of the deterrent posture elements, being a sign of coherence in itself.

A final element of alignment is that, ultimately, deterrence is not just a military endeavour.[44] Other levers of power can play a role, such as economic sanctions, financial restrictions and/or political pressure. NATO’s challenge is that it does not have those types of instruments, so cooperation with, for example the EU, might be an option to seek alignment since that organisation does have a number of other instruments of power. On the other hand, NATO member states have the ability to control other instruments they might use and align with military efforts. In the Brussels Summit of 2018 NATO recognised the primary responsibility of the targeted nation to respond to hybrid threats. Meanwhile, on that occasion NATO also concluded that in cases of hybrid warfare, the Council could decide to invoke Article 5 of the Washington Treaty, as in the case of an armed attack.[45] Furthermore, NATO is able to use dialogue and diplomacy alongside the military instrument of power. In 2002, in the aftermath of the Cold War referred to earlier, the NATO-Russia Council was established, which has an important role to play as a forum for dialogue and information exchange in order to reduce misunderstandings and increase predictability.[46] After Russia’s annexation of Crimea the dialogue by way of this Council was suspended, but after restarting in 2016 the Council has met two or three times every year. At the military leadership level SACEUR meets with the Russian Chief of the General Staff using this channel of communication to promote military predictability and transparency.[47]

Armed Forces Declaration by the NATO heads of state and government, Wales 2014. NATO’s deterrence starts with alignment in political decision-making, a challenge for a large organisation that needs consensus. Photo NATO

Conclusion

For about two decades deterrence did not get much attention within NATO, but since 2014 it has moved to the forefront again because of the significant changes in the security environment. Although the Cold War deterrence policy, mainly focussing on nuclear deterrence, has provided relevant experience, more than two decades later things have changed in such a way that deterrence has become more complicated than ever. The hybrid context requires a more coherent approach in which conventional forces, but also other instruments of power and the use of the information domain, play a vital role. Within that complexity, understanding the threat and its environment is a crucial requirement for effective deterrence. In applying deterrence, alignment is an essential leading principle from multiple perspectives. A lot has been put in place already since 2014 but still much will have to be done in the time to come. It will be a team effort within NATO with the involvement of NATO entities and the member states. This is crucial since the process of alignment may be equally important as the outcome itself. It is about alignment in a complex and demanding environment in which NATO and its member states face continuous challenges and threats. To overcome those is challenging in itself, but with a collective effort it is feasible. As Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg, referring to his NATO 2030 Initiative, stated at the Riga Conference 2020: ‘In a challenging security environment, we need to continue to invest in deterrence and defence.’[48] There is no doubt about the underlying reasons: credible deterrence is an important part of NATO’s principal task to ensure the protection of the citizens of its member-states and to promote security and stability in the North Atlantic area.

* Major General C.J. Matthijssen is currently the Deputy Chief of Staff Plans at NATO’s Allied Joint Force Command Brunssum (JFCBS). The article is written in a personal capacity. The author is indebted to Amb. Catherine Royle, Prof. Wyn Bowen, Col Nicole de Wolf-Fabricius and Maj Anne-Marij Strikwerda-Verbeek LL.M for their incisive feedback and valuable suggestions.

[1] NATO, ‘Remarks by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the Trident Juncture Distinguished Visitor’s Day’, 30 October 2018. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_159852.htm.

[2] NATO, ‘NATO Defence Ministers agree response to Russian missile challenge, address missions in Afghanistan and Iraq’, 17 June 2020. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_176392.htm.

[3] ‘NATO begins to develop a new concept of Deterrence and defense for the Euro-Atlantic area’, News Front, 10 July 2019. See: https://en.news-front.info/2020/07/10/nato-begins-to-develop-a-new-concept-of-deterrence-and-defense-for-the-euro-atlantic-area/.

[4] Kęstutis Paulauskas, ‘On deterrence’, NATO Review, 5 August 2016. See: https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2016/08/05/on-deterrence/index.html.

[5] Michael J. Mazarr, Understanding deterrence (Santa Monica, Rand Corporation, 2018). See: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE200/PE295/RAND_PE295.pdf.

[6] Mazarr, Understanding deterrence.

[7] Ibidem.

[8] Patrick M. Morgan, Deterrence: A Conceptual Analysis (Beverly Hills, Sage, 1977) 37.

[9] Michael J. Mazarr et al., What deters and why. Exploring requirements for effective deterrence of interstate aggression (Santa Monica, Rand Corporation, 2018). See: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2400/RR2451/RAND_RR2451.pdf.

[10] Matthew Kroenig and Walter B. Slocombe, ‘Why nuclear deterrence still matters to NATO’, Issue Brief, August 2014, Atlantic Council of the United States. See: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/183194/Why_Nuclear_Deterrence_Still_Matters_to_NATO.pdf.

[11] Paulauskas, ‘On deterrence’.

[12] Ibidem.

[13] NATO, ‘Declaration on a transformed North Atlantic Alliance’, 5 July 1990 (‘The London Declaration’). See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_23693.htm.

[14] NATO, ‘Lisbon Summit Declaration’, 20 November 2010. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_68828.htm.

[15] Paulauskas, ‘On deterrence’.

[16] ‘Russia to boost defense spending 59% by 2015’, RIA Novosti, 17 October 2012. See: https://web.archive.org/web/20130101191310/http://en.rian.ru/military_news/20121017/176690593.html.

[17] Molly K. McKew, ‘The Gerasimov Doctrine’, Politico, September/October 2017. See: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/09/05/gerasimov-doctrine-russia-foreign-policy-215538.

[18] Jonathan Marcus, ‘Crimea crisis quickens NATO’s steps’, BBC News, 2 April 2014. See: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26857741.

[19] Jan Broeks, ‘The necessary adaptation of NATO’s military instrument of power’, in: Militaire Spectator 189 (2020) (3). See: https://www.militairespectator.nl/sites/default/files/teksten/bestanden/Militaire Spectator 3-2020 Broeks.pdf.

[20] NATO, ‘Wales Summit Declaration’, 5 September 2014. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_112964.htm#mission.

[21] Simon Kemp, ‘Digital 2020: 3.8 billion people use social media’, We Are Social, 30 January 2020. See: https://wearesocial.com/blog/2020/01/digital-2020-3-8-billion-people-use-social-media.

[22] Antonia Ward, ‘ISIS’s use of social media still poses a threat to stability in the Middle East and Africa’, The Rand Blog, 11 December 2018. See: https://www.rand.org/blog/2018/12/isiss-use-of-social-media-still-poses-a-threat-to-stability.html.

[23] Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service, International security and Estonia 2020 (Tallinn, 2020). See: https://www.valisluureamet.ee/pdf/raport-2020-en.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3Wfvv5twTvNUGGVNwATbk_A7PD4RkPItn0evYWt2sirCV_vdgUdCSI-WQ.

[24] NATO, ‘Warsaw Summit Communiqué’, 9 July 2016. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm.

[25] Kilcullen refers to the ‘snakes’ as being mainly non-state actors/threats including terrorists and guerrillas and to the ‘dragons’ as being state-based competitors such as Russia and China.

[26] David Kilcullen, The Dragons and the Snakes (London, Hearst & Company, 2020) 17-18.

[27] McKew, ‘The Gerasimov Doctrine’.

[28] Charles K. Bartles, ‘Getting Gerasimov Right’, in: Military Review 96 (2016) (1). See: https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20160228_art009.pdf.

[29] ‘Putin approves Russia’s updated national security strategy’, TASS, 31 December 2015. See: https://tass.com/politics/848108.

[30] Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service, International security and Estonia 2020.

[31] Paul Stronski, ‘Late to the party: Russia’s return to Africa’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 16 October 2019. See: https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/10/16/late-to-party-russia-s-return-to-africa-pub-80056.

[32] Wyn Bowen, ‘NATO and the challenges of implementing effective deterrence vis-à-vis Russia’, Defence-in-depth, 16 May 2016. See: https://defenceindepth.co/2016/05/16/nato-and-the-challenges-of-implementing-effective-deterrence-vis-a-vis-russia/.

[33] Defence and Security Committee (DSC), ‘Reinforcing NATO’s deterrence in the East’, General Report, Joseph A. Day (Canada), General Rapporteur, 17 November 2018.

[34] NATO, ‘Deterrence and defence’, 10 November 2020. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_133127.htm.

[35] Jack Watling, ‘By parity and presence. Deterring Russia with conventional land forces’, RUSI Occasional Paper, July 2020. See: https://rusi.org/sites/default/files/by_parity_and_presence_final_web_version.pdf.

[36] Vytautas Keršanskas, ‘Deterrence: Proposing a more strategic approach to countering hybrid threats’, Hybrid CoE, March 2020. See: https://www.hybridcoe.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Deterrence_public.pdf.

[37] Axel Hagelstam, ‘Cooperating to counter hybrid threats’ , NATO Review, 23 November 2018. See: https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2018/11/23/cooperating-to-counter-hybrid-threats/index.html.

[38] Viljar Veebel and Illimar Ploom, ‘The deterrence credibility of NATO and the readiness of the Baltic states to employ the deterrence instruments’, in: Lithuanian Annual Strategic Review 16 (2017-2018). See: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Viljar_Veebel/publication/330315297_The_Deterrence_Credibility_of_NATO_and_the_Readiness_of_the_Baltic_States_to_Employ_the_Deterrence_Instruments/links/5c3b3a09299bf12be3c4f491/The-Deterrence-Credibility-of-NATO-and-the-Readiness-of-the-Baltic-States-to-Employ-the-Deterrence-Instruments.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

[39] Bowen, ‘NATO and the challenges of implementing effective deterrence vis-à-vis Russia’.

[40] NATO, ‘Press Conference by Air Chief Marshal Sir Stuart Peach, Chairman of the NATO Military Committee’, 14 May 2020. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_175786.htm?selectedLocale=en.

[41] NATO, ‘Deterrence and defence’. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_133127.htm.

[42] Bowen, ‘NATO and the challenges of implementing effective deterrence vis-à-vis Russia’.

[43] ‘Major investments in infrastructure needed to deter Russia’s incursion into Baltics — NATO general’, The Baltic Times, 2 August 2020. See: https://www.baltictimes.com/major_investments_in_infrastructure_needed_to_deter_russia_s_incursion_into_baltics_-_nato_general/.

[44] Bowen, ‘NATO and the challenges of implementing effective deterrence vis-à-vis Russia’.

[45] NATO, ‘Brussels Summit Declaration’, 11 July 2018. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_156624.htm.

[46] NATO, ‘NATO-Russia Council’, 23 March 2020. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_50091.htm.

[47] NATO ‘NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe, General Wolters meets with Russian Chief of General Staff, General Gerasimov’, 10 July 2019. See:

https://shape.nato.int/news-archive/2019/nato-supreme-allied-commander-europe--general-wolters-meets-with-russian-chief-of-general-staff--general-gerasimov.

[48] NATO, ‘Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the Riga Conference 2020’, 13 November 2020. See: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_179489.htm?selectedLocale=en.