Times are changing. After decades of peace in Europe war is now back on the continent, stimulating European states to reconsider the role of their armed forces. Investments in the armed forces are on the rise and focus is shifting from stability operations towards the original core task of the armed forces: the defence of (allied) territory. In the Dutch defence and security discourse, terms like ‘whole of society’ and ‘resilience’ are increasingly used, often accompanied by a reference to the Nordic countries. But what does a ‘whole of society’ approach mean and why do we need it? And how can we increase resilience in society? To find out, civil-military relations researchers visited Sweden and spoke with Minister of Civil Defence Carl-Oskar Bohlin and his State Secretary Johan Berggren.

Annelies van Vark and Huib Zijderveld*

Civil defence and resilience

The new Swedish government that came into office in the Fall of 2022 decided to strengthen the civilian components of total defence and to appoint a special minister of civil defence at the Ministry of Defence. What is civil defence and why and how is Sweden working to strengthen it?

The Swedish Home Guard exercises in Ystad. Photo Jonn Leffmann

Hosting us at the Ministry of Defence, Carl-Oskar Bohlin is visibly passionate about his work and convinced of its necessity. He explains that ‘the essence of civil defence is basically to get the whole of society to line up behind the effort of providing resistance against an antagonist or an aggressor’, with the aim of ‘securing the existence of the Swedish state’. The concept is in that sense basically the same as the one that was used during the Cold War: to make sure that in case of an armed assault resistance and resilience in all layers of society is high, and that the whole society is committed to helping the military defence to solve its tasks. Bohlin further explains that ‘resilience is about the will and the ability to resist armed aggression’. He points at Ukraine, which since the first invasion in 2014 has started to build up its civil defence and has proven to be successful during the second invasion and the war that is still going on today. As Bohlin points out, ‘They have been able to keep their electricity going while it has been under attack, while it has been a clear Russian aim to break the backbone of Ukrainian society by attacking the civil part of society.’ At the same time, ‘resilience has kept up the will to resist among the public of Ukraine.’

Security of supply

Johan Berggren adds, explaining that sustainability is important in that context, as ‘it’s not enough to be able to deal with something complicated or challenging for a few days or weeks, it (the war) goes on for a long time’. That goes for military defence as well, and an important part of the work being done at the ministry now is about how to achieve security of supply, for which cooperation with the private sector is essential. Bohlin explains: ‘I would say there is not one task within the military or in civil defence that can be maintained without the help or the participation of private entities.’ He is not only talking about building stockpiles, but also about the possibilities to redirect production, which is not only important in times of war, but also during crises other than war, such as disasters and complex emergencies. The COVID-19 pandemic is an example that immediately comes to mind. During that time production was redirected ‘almost organically’, to produce masks or sanitation equipment for example, but ‘it needs to be more institutionalized, so that we have a preparedness for that in advance.’

Sense of urgency

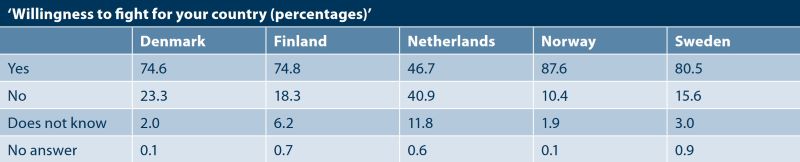

An essential precondition to rebuild civil defence is a sense of urgency in society. Bohlin sees ample evidence in Swedish society for a growing sense of urgency, indicated for example by an increased will to defend Sweden in the general population and by a very large influx of volunteers into the voluntary defence organizations Sweden has. He explains that the government has been actively pushing this sense of urgency, ‘since we find ourselves in a very dire security situation, in which we don’t know what lies around the corner. We don’t know where the endgame in this might take us.’ He does not foresee a situation in which the current situation will go away and go back to prior 2014, or 2008. In addition Berggren explains that Sweden’s geographical situation is very different from that of the Netherlands or countries further southwest: ‘Sweden is where it is, and we have always lived under the shadow of the East.’

Survey ‘Willingness to fight for your country’, C. Haerpfer, R. Inglehart, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin, and B. Puranen (Eds.), World Values Survey: Round Seven - Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat (2020).

What can a country like the Netherlands, where the sense of urgency is at a much lower level, learn from Sweden in this respect? Bohlin is very clear on this issue: ‘We need to prepare ourselves for a worse scenario than we are finding ourselves in right now. And that is a concern for every European country I would say.’ Berggren continues by saying: ‘Geographically, the Netherlands may be far away from the front lines, but in modern days geography matters less.’ One can think about cyber sabotage, espionage, or other grey zone threats. Not to forget the port of Rotterdam: ‘I believe Rotterdam is the biggest port in Europe and would be a key point of entry for reinforcements into Western Europe’, which would make it a target for an aggressor.

Conscription and voluntary defence

As part of the effort to rebuild civil defence, Sweden has decided to reactivate conscription, starting with 4,000 conscripts per year in 2018, and expanding the total number of conscripts to 8,000 in 2025, including both men and women. The whole cohort receives a call-up letter when they are 18 and are obliged to fill out a digital form. Based on their qualifications and motivation, around 20,000 young people are invited for a medical check-up and two days of briefings, after which the final selection takes place.

As the numbers of draftees are (still) relatively low at around 10 per cent of the cohort, the Swedes are selective in their recruitment procedures, only allowing the most capable and motivated to serve, as Johan Berggren explains. After fulfilling their conscription, former conscripts are placed in a reserve unit for 10 years and can be called up to serve in case of a state of high alert.[1]

Minister of Civil Defence Carl-Oskar Bohlin (right) and his State Secretary Johan Berggren. Photo Government Offices of Sweden, Tom Samuelsson

An important ambition for Carl-Oskar Bohlin is to establish civil conscription as a complement to military conscription, starting in the sector of the rescue services, which are a municipal responsibility. He explains: ‘The experiences from Ukraine show the enormous amount of stress that the rescue services are under in terms of equipment requirements, personnel and new tasks.’ What comes to mind is, for example, clearing unexploded ammunition and recovering people from collapsed buildings. This makes the rescue services the logical starting point for the establishment of civil conscription. An enquiry is currently underway, looking at other sectors where civil conscription would be useful, ‘similar to what we had during the Cold War, when we had civil conscription for people working with power lines, and in health care, functions that need extra support during an assault.’

By preparing for the worst (an armed attack on Sweden) the country is also better prepared for disasters and complex emergencies. In addition to government organizations, voluntary defence organizations play an important role. Bohlin explains that voluntary defence organizations get government funding to fulfil certain tasks during a peacetime crisis but also during high alert or an armed assault. Around 350,000 Swedes are members of such a voluntary defence organization and usually they are connected to different municipalities and have arrangements to assist during peacetime crises. As these voluntary defence organizations were never abolished or scaled down, ‘they have the institutional memory of Swedish civil defence from before.’

Domestic role of the armed forces

The main purpose of civil defence is to funnel all of society’s efforts into one direction: to protect the Swedish state from an armed aggressor. However, in peacetime the armed forces can support civilian authorities as well. An important principle in the Swedish governance model is the responsibility principle, ‘which means that the agency or actor that has the responsibility for a task during peacetime, also has that responsibility during crisis or ultimately war, with some exceptions.’ Bohlin illustrates this with an example from the rescue services, which are primarily responsible in case of an earthquake or a flood, for example, but can escalate up the chain, if necessary. ‘Ultimately, the state can also ask for military assistance to provide resources to help out in a peacetime crisis.’ The armed forces can in that sense be seen as the last resort in case of civil crises and can provide assistance when needed. On the other hand, he explains, ‘in the event of an armed assault or attack on Sweden, all of civil society is then committed to support the military defence to carry out its task.’

Lessons learned

What is the main lesson the Netherlands can learn from the Swedish system for civil defence? Referring to the low popular commitment to defend the Netherlands, Bohlin is very clear: ‘Getting the whole of society involved raises awareness about what is the ultimate task that needs to be carried out. Resilience and resistance start with your own personal preparedness and your own will to defend.’ A holistic approach involving the whole of society may eventually lead to a higher will to defend as well ‘because it comes closer to every citizen. It is not only the people in uniform who are carrying out the total defence effort, it is every individual within society that has to feel engaged when doing that.’

* Annelies van Vark is Senior coordinating adviser at the Transition Team, Defence Staff and PhD candidate at Leiden University. Captain Huib Zijderveld is a PhD candidate at the Netherlands Defence Academy and Free University Amsterdam.

[1] If the Swedish government judges that Sweden is at war, or that war is imminent, it can declare a ‘state of high alert’. During a ‘state of high alert’ the government's powers increase and there are a set of pre-prepared laws that ensure that Sweden can secure its needs for resources and personnel, amongst other things.