Concepts such as Information Warfare, Information Operations, Influence Operations, Intelligence, and Cyberspace and Electromagnetic Activities, to mention but a few, compete with Information Manoeuvre for prominence and together cloud the conceptual field. As a result, Information Manoeuvre is at risk of being shrouded in ambiguity. Divergence of interpretations and misunderstandings could hamper successful implementation of the concept and trigger intra-organizational disputes about responsibilities. Therefore, there is a need to provide clarity on the conceptual foundations of Information Manoeuvre and the manner in which it is interpreted within the Netherlands Ministry of Defence.

Throughout human history, from Sun Tzu, via Alexander the Great, to the current war in Ukraine, information has played a prominent role in the conduct of war. Nevertheless, while the use of information is nothing new to armed conflict, the process of ‘informatisation’ has in recent decades had a major impact on our societies, and by extension, on modern warfare.[1] To capture and adapt to the resulting changes in the operational environment, the concept of Information Manoeuvre was introduced in the Royal Netherlands Army. The concept quickly rose to prominence, leading to the establishment of the Land Information Manoeuvre Centre (LIMC), the founding of the Information Manoeuvre Arm,[2] and the adoption of the concept as a new vision of the conduct of future military operations.[3]

To capture and adapt to the resulting changes in the operational environment, the concept of Information Manoeuvre was introduced in the Royal Netherlands Army. Photo MCD, Gerben van Es

Notwithstanding its popularity, the term Information Manoeuvre is not universally acknowledged. In fact, it has only been adopted by the armies of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. In academic circles it is a similarly uncommon term. Yet, a plethora of terms exists to describe similar or overlapping notions and approaches. Concepts such as Information Warfare, Information Operations, Influence Operations, Intelligence, and Cyberspace and Electromagnetic Activities, to mention but a few, compete with Information Manoeuvre for prominence and together cloud the conceptual field. As a result, the concept is at risk of being shrouded in ambiguity. Divergence of interpretations and misunderstandings could hamper successful implementation of the concept and trigger intra-organizational disputes about responsibilities. Therefore, this article aims to provide clarity on the conceptual foundations of Information Manoeuvre and the manner in which it is interpreted within the Netherlands Ministry of Defence (MoD). To do so, the underlying concepts of Information and Manoeuvre are examined before a comprehensive definition of Information Manoeuvre is provided and its interpretation within the MoD explored.

The meaning of ‘information’

‘Information’ might seem a self-explanatory and commonly understood term. Yet, in reality, it is quite ambiguous. In general, four different conceptualizations of information can be distilled. These conceptualizations are not mutually exclusive and can exist side by side. Yet, depending on the context in which the term ‘information’ is used, either may be dominant.[4]

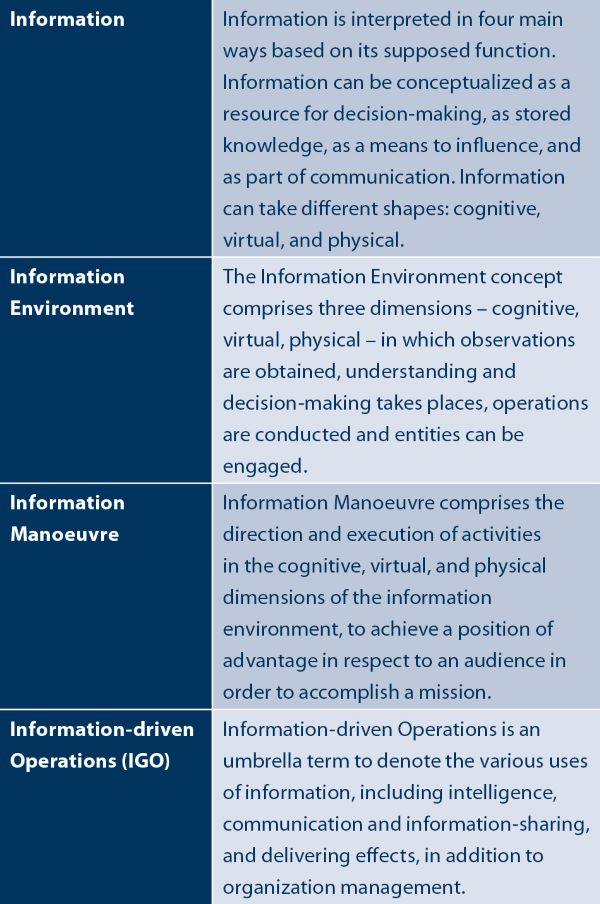

Overview of key concepts

Information as a resource for decision-making

Information can be treated as purely consisting of data in the environment, which may comprise various types of data, from objects and events to sounds and smells. Anything that can be observed, measured, processed, and analysed is considered to be information.[5] In military tradition, such data are considered a resource for (understanding and) decision-making. Information understood as a resource corresponds to the interpretation of intelligence as ‘information that meets the stated or understood needs of [decision-makers] and has been collected, processed, and narrowed down to meet those needs’.[6] As such, information as a resource is considered to be one of the main functions of military conduct.[7] NATO states that intelligence is an ‘aid to provide situational awareness, develop understanding and is a critical tool for decision-making’.[8] In this way, intelligence can bestow a ‘decision advantage’ or ‘information edge’ upon decision-makers.[9]

Information as stored knowledge

Information can be considered as a representation of knowledge in a physical, digital, or cognitive form.[10] The principles and practices that armed forces take into account when pursuing their objectives is enshrined in military doctrine and policy and is stored in the experience and education of military personnel. All this knowledge forms a frame of reference against which individuals judge new information they encounter.[11] In this manner, knowledge presents an internal resource which, together with external data, provides the basis upon which to develop understanding of a situation.[12] The perspective of information as knowledge is present in much of day-to-day military conduct, especially in the areas of military science and in education and training departments.

Information as a means to influence

Information can be understood as a message, as something that can be produced, distributed, manipulated, and controlled and can therefore be used by the sender in different ways and for various purposes.[13] This perspective is based on the assumption that the receiver’s observation and subsequent interpretation of the message can be steered toward the sender’s intentions in a process of communication that is both deliberate and purposeful. This, too, is a perspective familiar to armed forces that have used information to gain an advantage over opponents by disrupting their decision-making.[14] Similar to intelligence, the military tradition of deception is said to be ‘as old as warfare itself’.[15] There is a wide variety of methods used to deceive an audience, including dissimulation (hiding true information) and simulation (showing false information), denying information, misdirection, spreading disinformation, increasing ambiguity, and targeted misleading.[16] Using information to influence the perceptions, attitudes and behaviour of relevant actors is also one of two facets subsumed under the information function of modern military conduct.[17]

Information as part of communication

Information can be conceptualized as being part of the communication process. It emphasizes that information is a feature of every human interaction and that understanding is heavily dependent upon human behaviour and sense-making processes.[18] In military organizations, information plays a crucial role as part of the internal communication and information-sharing processes. Two functions of military conduct are – at least partially – concerned with ensuring an efficient information flow: command and control and the information function.[19] For both these functions it is important that information is managed in such a way that all departments at all levels in the organization have access to the required information when necessary. In this process, modern information infrastructure and appropriate procedures are vital to ensure information-sharing throughout the organization.

Modern information infrastructure and appropriate procedures are vital to ensure information-sharing throughout the armed forces. Photo MCD, Gerben van Es

The information environment

These four conceptualizations of information denote the different ways in which the function, purpose, and character of information can be interpreted. Yet, information can take on many different shapes. Information is not limited to written or spoken words but also includes all information that can be found in a person’s mind and in social settings, such as beliefs, thoughts, opinions, norms, values, and emotions. In addition, information can be found in virtual forms, for instance as social media profiles, email-addresses, text messages, bits, and software. A third shape that information may take is a physical one, in the form of people, (network) infrastructure, and terrain, to add some examples. These three categories of information are also called the dimensions – cognitive, virtual, and physical – that together make up the ‘information environment’.[20] The information environment construct describes the setting in which understanding and decision-making takes places and operations are conducted, what kind of entity is engaged or targeted and in which of the three dimensions this occurs.

The notion of an information environment allows for the co-existence of the different conceptualizations of information. When viewing information through the ‘resource’ lens, the three dimensions can be considered as three different categories of data to be observed. For example, the beliefs and values of certain individuals can be examined in the cognitive dimension, social media profiles can be assessed in the virtual dimension, and behaviour can be analysed in the physical dimension. Alternatively, when taking on the perspective of information as a means, those three dimensions provide both the tools and targets to influence the decision-making processes of others. For example, individuals may be persuaded to alter their behaviour by persuasion in the cognitive dimension; text and visual data can be manipulated in the virtual dimension whereas infrastructure can be disrupted or destroyed in the physical dimension.

Conceptualizations in a generic decision-making process

The different conceptualizations of information appear at different moments throughout the decision-making process, comprising a sequence starting with observing, understanding, deciding, orchestrating and, finally, acting. The resulting activities or the consequences thereof can themselves be observed, thus continuing the cycle. When the environment is observed and analysed, information is conceptualised as a resource for decision-making. Here, pre-existing knowledge plays a role in shaping the interpretation of external observations. When attempting to generate effects in the information environment, information is conceptualised as a means to do so. When ensuring a properly functioning information flow throughout the decision-making process, information is conceptualized as communication. The different conceptualizations of information at different stages in the decision-making process are visualized in figure 1.

Figure 1 Conceptualizations of information in decision-making [21]

It must be highlighted how important one’s perspective is when considering the information concept. Not only can the way that information is understood differ at various points in the decision-making process but it also makes a difference whether information is viewed from the perspective of one’s own forces or rather from the perspective of the audience. For example, information that is viewed as a resource for one’s own forces and can in fact be the instrument of opponents in an attempt to influence, and vice versa. Therefore, what is a resource to one party can actually be a means for another and, conversely, what may be a means to one side can be viewed as a resource to the other. These relationships are demonstrated in figure 2.

Figure 2 Information in one’s own decision-making process compared to the audience’s[22]

Manoeuvre

Manoeuvre is a concept that may be difficult to grasp and, although it is laid down in doctrine, it is not always universally understood.[23] The term may take on different meanings, depending on the context in which it is used, and ‘has a possible applicability at every level of warfare, in all environments, and throughout the spectrum of military activity’.[24] The most general definition of manoeuvre as a noun is that of ‘a movement or set of movements needing skill and care’.[25] This perspective is also found in a military context where the traditional form of manoeuvre is indeed most often related to physical movement. An alternative interpretation of manoeuvre sees it as an attempt ‘to control or influence a person or situation in a particular way’.[26] The latter of these two emphasises cunningness and cleverness in an attempt to manipulate or otherwise influence someone.[27] This does not necessarily include physical movement but is primarily concerned with the mind.

As Kiszely points out, the most common military interpretation of manoeuvre combines the two interpretations.[28] As a combination of a physical and mental activity, manoeuvre is also defined by NATO as the ‘employment of forces on the battlefield through movement in combination with fire, or fire potential, to achieve a position of advantage in respect to the enemy in order to accomplish the mission’.[29] Manoeuvre is also an official joint function of military conduct.[30] In this regard, manoeuvre includes the focus on targeting an actor’s weak points, the clever directing of fighting power, and the emphasis on the mental as much as on the physical component.[31] This is the spirit of what has been termed the ‘manoeuvrist approach’, i.e. an approach that emphasises ‘shattering the enemy’s overall cohesion and will to fight’.[32] To concretise the means by which this goal is achieved, this classic form of manoeuvre relies on ‘attacks on the enemy’s command and control systems and the requirement for high tempo and simultaneity’.[33] As a broad concept, varying forms of manoeuvring can be found across the spectrum of military activity. It may include the decision-making, orchestration, and execution phases of the decision-making process and take place at all levels of conflict.[34]

Information Manoeuvre

The term Information Manoeuvre is the joining of the words ‘information’ and ‘manoeuvre’. The complexity of the information aspect and the breadth of the manoeuvre aspect complicates defining Information Manoeuvre. Information does not have a straightforward definition; instead, four conceptualisations of information exist that are dependent on the context in which the term ‘information’ is used. In addition, it has been asserted that information can take a physical, digital, or cognitive shape. What follows is that it is in these three dimensions of the information environment that information manoeuvre takes place.

The previously discussed principles of manoeuvre have a number of implications for the Information Manoeuvre concept. It means that Information Manoeuvre combines the two facets of manoeuvre: it comprises movement or action as well as the ‘deceptive, elusive, scheming adroitness’ that causes someone to be influenced or manipulated. [35] Information Manoeuvre emphasises the exploitation of the audience’s vulnerabilities and the clever directing of activities where they can have maximum effect. As a result, it underlines economy of effort. In addition, manoeuvring in the information environment relies on the intelligent use of methods in all three of its dimensions instead of relying purely on kinetic methods. Similar to manoeuvre as previously characterized, Information Manoeuvre can just as well be concerned with the mind as with physical action. Furthermore, manoeuvre can involve both decision-making and planning and the execution of those decisions and plans at all three levels of conflict.[36] The same therefore applies to Information Manoeuvre, which is concerned with the decision-making, coordination, and execution of actions in the information environment.

These considerations lead to the following definition: Information Manoeuvre comprises the direction and execution of activities in the cognitive, virtual, and physical dimensions of the information environment, to achieve a position of advantage in respect to an audience in order to accomplish a mission.

Figure 3 Information Manoeuvre in decision-making[37]

Similar to ‘regular’ manoeuvre, Information Manoeuvre can be likened to a game of chess, with ‘one opponent seeking to mentally outmanoeuvre the other’, which may involve physical action but does not require it.[38] If manoeuvring in the information environment involves the use of information with the intention to get an advantage, information is thus primarily seen as the instrument or means to do so. Information Manoeuvre therefore seems to be most strongly associated with the conceptualization of information as a means. What follows from this is that the purpose of Information Manoeuvre is to gain an advantage by affecting the decision-making of a target audience. Nevertheless, information used as a resource and information used as communication are both prerequisites to the functioning of military operations.[39] Hence, they are also essential to Information Manoeuvre.

Information Manoeuvre can include any activity that takes place in any dimension of the information environment, which in any shape or form attempts to deliberately affect, influence, manipulate, or disrupt the perceptions, attitudes, behaviour and, ultimately, the decision-making of a target audience in a favourable direction. As such, Information Manoeuvre has adopted the breadth of the manoeuvre concept. Therefore, familiar disciplines and concepts such as command and control warfare, public affairs, strategic communications, psychological operations, cyber and electromagnetic activities, as well as kinetic action, to mention but a few, can all be used for Information Manoeuvre. Influencing an audience’s decision-making process can, for example, take the shape of influencing a target group through a public affairs campaign, through undermining the audience’s informaftion and communication systems, or through something as traditional as the use of physical decoys. Therefore, while there is a wide variety of available tools and methods, when used to manoeuvre in the information environment, they share the fundamental aim to achieve a position of advantage in respect to an audience.

The first alternative interpretation considers Information Manoeuvre to be nearly equivalent to the concept of Information-driven Operations. Photo US Marine Corps, Jerrod Moore

Information Manoeuvre in the MoD

The complexity of the Information Manoeuvre concept and the ambiguity surrounding the constituting terms ‘information’ and ‘manoeuvre’ potentially leave room for divergent interpretations. To investigate the presence of such alternative interpretations within the Dutch MoD, policy documents and other official publications were scrutinized and interviews conducted. These anonymised interviews were held with six subject-matter experts associated with some of the military organizations involved in the implementation or execution of Information Manoeuvre.[40] The Army Staff and Directorate-General for Policy (DGB)[41] were chosen to include staff and policy level perspectives on the concept. The Land Information Manoeuvre Centre (LIMC) was chosen because of its singular focus on information manoeuvre, and the Military Intelligence and Security Service (MIVD)[42] in order to include an intelligence perspective on Information Manoeuvre. The results of this examination demonstrate a significant variation in the manner in which Information Manoeuvre is understood. Three of the most prominent deviations from the previously established definition are discussed. These deviations are related to each other and might stem from a confounded understanding of ‘information’. Conceptualizations of information as a resource intertwine with those that see information as a means and those that see information as communication to create a muddled understanding of what it means to manoeuvre in the information environment.

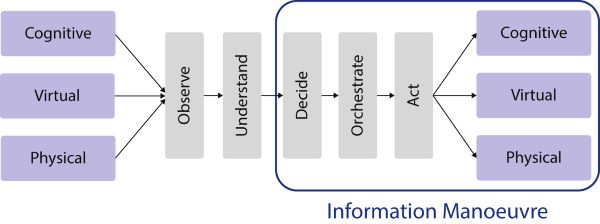

#1 Information Manoeuvre ~ Information-driven Operations

The first alternative perspective on Information Manoeuvre is one that broadens the definition of Information Manoeuvre significantly. This interpretation considers Information Manoeuvre to be nearly equivalent to the concept of Information-driven Operations (IGO) (see figure 4).[43] IGO is generally understood to be an umbrella term to denote the various uses of information, including intelligence, communication and information-sharing, and delivering effects.[44] Moreover, to complicate matters even further, the term IGO is also used to refer to organization management outside operations. IGO therefore includes not only a perspective on information as a means to generate effects, but also as a resource for decision-making and as communication. As such, IGO is a much broader concept than Information Manoeuvre, which is based on the conceptualization of information as a means to generate effects. Nevertheless, the perspective that equates Information Manoeuvre with IGO was found to be pervasive, encountered both in a document published by the Army Staff and in an interview with a subject-matter expert.[45] In this interpretation, Information Manoeuvre is the military translation of the IGO concept, more concerned with operational affairs than with data management and organizational processes, yet in most ways identical. What this interpretation does is consider Information Manoeuvre as essentially a catch-all phrase; a concept that encompasses most, if not all, uses of information in a military organization.

Figure 4 Information Manoeuvre as the equivalent of IGO

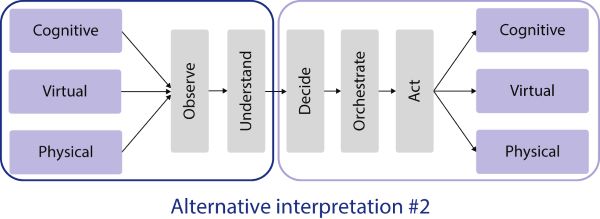

#2 Information Manoeuvre ~ Intelligence 2.0

Intelligence was previously defined as ‘information that meets the stated or understood needs of [decision-makers] and has been collected, processed, and narrowed to meet those needs’.[46] This process of collecting and processing information to support decision-making was argued to be critically important to, yet fundamentally distinct from, Information Manoeuvre. Nevertheless, the second alternative perspective considers intelligence, or intelligence-like processes and activities, as part of Information Manoeuvre (see figure 5).

In some cases, intelligence was very deliberately mentioned and included as part of Information Manoeuvre.[47] In other cases, intelligence was not referred to as such but still consciously included, albeit through the use of alternative terminology. Both the Delphi Study and the Army vision on IGO documents use the term ‘information exploitation’ to denote the identical process of collecting and processing information to support decision-making.[48] Yet in other cases, intelligence-like processes and activities were included in a much more unconscious manner. For example, some interviewees did not include intelligence or ‘information exploitation’ in their definition of Information Manoeuvre. Instead, they emphasized its fundamental goal of generating effects. However, they contradictorily implied that the use of novel technologies to gather better and more timely information with the intention to create or improve situational awareness is considered Information Manoeuvre.[49]

This perspective on Information Manoeuvre is evocative of an Intelligence 2.0 approach.[50] It emphasizes that in modern conflict ‘the side with better information that could be refined into knowledge to guide tactical and strategic decision-making’ has the edge over its opponents.[51] This search for an ‘information edge’ is fundamentally different by nature from the search for a way to influence an audience through activities in the information environment. Due to their different goals and functions, they serve to distinguish between the two to prevent confusion and muddling their conceptual underpinnings.

The unclear relationship between the terms Intelligence and Information Manoeuvre is also visible in discussions on responsibilities. The confounding of these concepts could become problematic if the blurred distinction between the two terms is reflected in a similarly blurred distinction in legal mandates and responsibilities. See for example the discussions surrounding the LIMC experiment.[52] In addition, the broad interpretation of Information Manoeuvre as including intelligence or intelligence-like processes and products risks clashing with the interpretations of intelligence work as described by some respondents. Some interviewees argued that the narrow view of intelligence organizations as solely concerned with developing understanding is somewhat outdated.[53] As such, a broad and ambiguous understanding of the Information Manoeuvre concept could risk blurring responsibilities between armed forces and intelligence organizations.

Figure 5 Information Manoeuvre as Intelligence 2.0

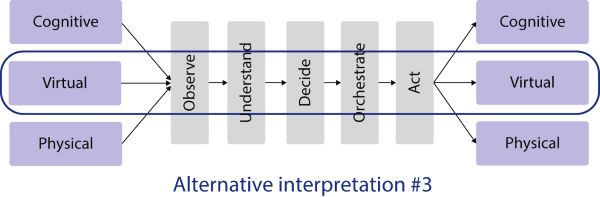

#3 Information Manoeuvre ~ the virtual dimension

This alternative interpretation of Information Manoeuvre strongly emphasizes manoeuvring in the virtual dimension, cyberspace, and the electromagnetic spectrum (see figure 6). The definition as previously formulated in this article underscored that manoeuvring in the information environment can take place in the cognitive, virtual, and physical dimensions. Yet, the view of Information Manoeuvre as primarily concerned with activities in cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum proved to be pervasive. A draft policy document divided Information Manoeuvre into two main types of operations: Cyber Operations, which seek to deliver effects primarily in and through the virtual dimension, and Information Operations, which aim to deliver effects primarily in and through the cognitive dimension.[54] This is already more limited than the definition adopted in this article, which also includes activities in the physical dimension. However, one interviewee emphasized the virtual dimension even more, pointing out that activities in the cognitive dimension which aim to directly influence the behaviour of a target audience, are considered to be very sensitive and are often shied away from.[55] As a result, more emphasis is put on activities in the virtual dimension.[56] Another interviewee went even further in underlining the importance of the virtual dimension, arguing that the distinguishing feature of Information Manoeuvre lies in its use of cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum. In this interpretation the cognitive, and, to a lesser extent, the physical dimension is affected exclusively through the virtual dimension.[57] It is not unreasonable to assume that cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum will play an increasingly important role in Information Manoeuvre. Yet, this alternative perspective could risk creating conceptual confusion due to potential for conflating the terms Information Manoeuvre and Cyber Operations.

Figure 6 Information Manoeuvre as primarily concerned with the virtual dimension

Conclusion

This article set out to provide clarity on the conceptual foundations of Information Manoeuvre and the manner in which it is interpreted within the Netherlands MoD. Information was shown to be conceptualized in four distinct manners: as a resource for decision-making, as stored knowledge, as a means to influence, and as a part of the communication process. Information can take shape in cognitive, virtual, or physical form, which are the three dimensions that together make up the ‘information environment’ in which military organizations operate. Assuming that Information Manoeuvre is essentially manoeuvre that takes place in the information environment, the following definition can be formulated: Information Manoeuvre comprises the direction and execution of activities in the cognitive, virtual, and physical dimensions of the information environment with the aim to achieve a position of advantage in respect to an audience in order to accomplish a mission.

The interpretations of Information Manoeuvre have been shown to differ quite significantly within the MoD. Three main deviations could be discerned, which sometimes overlap. One alternative perspective considers Information Manoeuvre to be the military translation and near equivalent of Information-driven Operations (IGO). Another perspective sees Information Manoeuvre as essentially Intelligence 2.0. A third deviation regards Information Manoeuvre as an approach primarily concerned with the virtual dimension. These deviations might stem from a confounded understanding of what ‘information’ is. Contextual factors and personal experience determine which of the four conceptualizations of information is dominant. At the same time, the manner in which information is conceptualized has major consequences for the way in which a concept such as Information Manoeuvre is interpreted. The identified interpretations vary to the extent that the differences in understanding could hamper communication and lead to misunderstandings. The obvious risk is that ‘using these same terms differently in different contexts is likely to create conceptual confusion that in turn can also result in misallocation and misalignment of resources and capabilities.’[58] Clarity, specificity, and consistency are absolutely key aspects for the successful implementation of a new approach or vision.[59] Indeed, the field of information-related approaches to warfare is riddled with concepts that have been rendered essentially useless due to the lack of accurate definition, incomprehensibility, and inconsistency in their use. [60] If the Information Manoeuvre concept is to remain relevant, it must rise above the terminological issues that plague the field and be defined and employed in a sharp, clear, and simple manner.

[1] Jelle van Haaster, On Cyber: The Utility of Military Cyber Operations during Armed Conflict (University of Amsterdam, 2019) 70-84; Roy van Keulen, Digital Force: Disrupting Life, Liberty and Livelihood in the Information Age (Leiden University, 2018) 19-38.

[2] Paul Ducheine, Corstiaan de Haan and Norbert Moerkens, ‘Informatiemanoeuvre en nieuwe traditieverbanden in de Koninklijke Landmacht’, Militaire Spectator 190 (2021) (5) 258-267.

[3] Royal Netherlands Army, Information-Driven Operations for the Royal Netherlands Army: Manoeuvring in the Information Environment (2020) 11.

[4] Maureen McCreadie and Ronald Rice, 'Trends in Analyzing Access to Information. Part I: Cross-Disciplinary Conceptualizations of Access, Information Processing and Management 35 (1999) 46-48.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Mark Lowenthal, Intelligence. From Secrets to Policy (Thousand Oaks, SAGE Publications, 2020) 1.

[7] NATO, Allied Joint Doctrine for the Conduct of Operations – AJP 3 (2019) 1.23; Ministry of Defence, Netherlands Defence Doctrine (The Hague, 2019) 90-91.

[8] NATO, AJP 3, 1.23.

[9] Peter Oleson (ed.), Guide to the Study of Intelligence (Falls Church, Association of Former Intelligence Officers, 2016) 4.

[10] McCreadie and Rice, 'Trends in Analyzing Access to Information', 9; Van Haaster, On Cyber, 184-185.

[11] Rasha Abdel Rahman and Werner Sommer, 'Seeing What We Know and Understand. How Knowledge Shapes Perception', Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 15 (2008) (6) 1055-1061.

[12] Idem, 2.5.

[13] McCreadie and Rice, 'Trends in Analyzing Access to Information’, 46-48.

[14] Hy Rothstein and Barton Whaley (eds.), The Art and Science of Military Deception (Boston, Artech House, 2013) xix; Peter Pijpers and Paul Ducheine, 'Deception as the Way of Warfare. Armed Forces, Influence Operations and the Cyberspace Paradox', The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2023.

[15] Mark Lloyd, The Art of Military Deception (Barnsley, Pen & Sword Books Limited, 1997) 1.

[16] Han Bouwmeester, Krym Nash. An Analysis of Modern Russian Deception Warfare (Utrecht University, 2020) 95-102.

[17] NATO, AJP 3, 1.24.

[18] McCreadie and Rice, 'Trends in Analyzing Access to Information’, 46-48.

[19] NATO, AJP 3, 1.22-1.24.

[20] Van Haaster, On Cyber, 184-185.

[21] Note. Adapted from Peter Pijpers and Paul Ducheine, ''If You Have A Hammer…’ Reshaping The Armed Forces’ Discourse On Information Maneuver', Amsterdam Law School Research Paper 34 (2021) 1-20.

[22] Idem.

[23] John Kiszely, 'The Meaning of Manoeuvre', RUSI Journal 143 (1998) (6) 36.

[24] Idem, 40.

[25] Cambridge Dictionary, s.v. ‘manoeuvre’, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/manoeuvre.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Kiszely, 'The Meaning of Manoeuvre’, 36.

[28] Ibid.

[29] NATO, Glossary of Terms and Definitions AAP-06 (2013) 2M.2.

[30] NATO, AJP 3, 1.21; Ministry of Defence, Netherlands Defence Doctrine, 90.

[31] Ministry of Defence, Netherlands Defence Doctrine, 90.

[32] Kiszely, 'The Meaning of Manoeuvre’, 37.

[33] Ibid.

[34] S. Davison, 'Manoeuvre,' Australian Defence Force Journal 152 (2002), 43-48.

[35] Kiszely, 'The Meaning of Manoeuvre', 36.

[36] Davison, 'Manoeuvre', 43-48.

[37] Note. Adapted from Pijpers & Ducheine, ‘If You Have A Hammer…’.

[38] Kiszely, 'The Meaning of Manoeuvre’, 36.

[39] NATO, AJP 3, 1.21-1.24.

[40] Due to their anonymized nature, the transcripts of the interviews are not published.

[41] Abbreviation in Dutch.

[42] Abbreviation in Dutch.

[43] Abbreviation in Dutch.

[44] Ministerie van Defensie, 'Kamerbrief Beleidsvisie Informatiegestuurd Optreden' (The Hague, 2023), https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2023/07/04/kamerbrief-beleidsvisie-informatiegestuurd-optreden; Royal Netherlands Army, Information-Driven Operations, 11.

[45] Interview #1, interview by author, May 24, 2022; Interview #4, interview by author, June 21, 2022.

[46] Lowenthal, Intelligence. From Secrets to Policy, 1.

[47] Interview #1, interview by author, May 24, 2022.

[48] Ministerie van Defensie, Informatie als wapen, middel en doel (The Hague, 2016); Royal Netherlands Army, Information-Driven Operations.

[49] Interview #3, interview by author, June 14, 2022; Interview #4, interview by author, June 21, 2022.

[50] Term used by Pijpers & Ducheine, ‘If You Have A Hammer…’.

[51] John Arquilla, Bitskrieg. The New Challenge of Cyberwarfare (Cambridge, Polity Press, 2021) 14.

[52] Commissie-Brouwer, onderzoeksrapport LIMC Grondslag gezocht, 2023.

[53] Interview #2, interview by author, June 9, 2022.

[54] Ministerie van Defensie, IGO: Informatie als doel, middel en wapen (draft version 5-01-22) (The Hague, 2022) 21-23. [document is archived with author].

[55] Interview #3, interview by author, June 14, 2022.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Interview #4, interview by author, June 21, 2022.

[58] Herbert Lin, 'Doctrinal Confusion and Cultural Dysfunction in DoD', The Cyber Defense Review 5 (2020) (2), 100.

[59] Sergio Fernandez and Hal Rainey, 'Managing Successful Organizational Change in the Public Sector', Public Administration Review 66 (2006) (2) 169-170.

[60] Martin Libicki, Conquest in Cyberspace. National Security and Information Warfare (New York, Cambridge University Press, 2007) 17-19.