Following the initial failure of the Russian invasion of Ukraine that began on February 24, 2022, fighting along the front has largely degenerated into a grinding war of attrition, characterized by positional - often urban – warfare, remotely conducted (precision) strikes and meeting engagements between relatively small-scale manoeuvre elements. While this article is being written the Ukrainian summer offensive has only been steadily progressing. Nonetheless, approximately one year before, on September 6, 2022, Ukrainian forces unleashed a daring counter-offensive around Kharkiv that quickly developed into a stunning success. As the only such one in the war thus far, it represented a feat of arms that, according to some, was reminiscent of the German Blitzkrieg years.[1] In a mere six days Ukrainian forces re-conquered a territory of around 6,000 square kilometres and advanced up to 70 kilometres deep into Russian-held territory, threatening Russian forces with encirclement, forcing them into a headlong retreat and capturing a vast amount of Russian military equipment.[2]

Captain Randy Noorman, MA*

Although it sometimes seems as if a military article is never complete unless Clausewitz is quoted somewhere along the way, in this case it is his contemporary military theorist, Antoine-Henri de Jomini (1779-1869), who comes to the fore. In search of an overarching universal theory of warfare, Jomini, in his time, came up with a number of maxims, principles and related terminology, or, in some cases, adopted and adjusted them from his immediate predecessors who maintained a rather mathematical and geometrical approach to warfare. Even though Jomini’s approach contradicts Clausewitz’s nowadays more commonly accepted views on warfare as being far too complex and therefore unpredictable and irreducible to a set of fixed principles, it has retained certain values.[3]

Ukrainian servicemen walk nearby Izyum. This city can be described as the decisive strategic point along the northern front. By utilizing their interior lines of operation, and along the lines of Jomini’s concepts, the Ukrainian army was able to establish a concentration of forces in this area during its September 2022 Kharkiv offensive. Photo ANP, EPA, Oleg Petrasyuk

Campaigns and battles do not occur in perfect isolation and history offers numerous examples in which Jomini’s principles and concepts have not led to victory. The enemy gets a vote, as the saying goes. On the other hand, history also offers plenty of examples where they did. As the Kharkiv offensive demonstrates, even modern operations can be planned and analysed using Jominian concepts and principles. At least, it provides a valuable framework and accompanying terminology to geographically denote military operations. It is therefore not without reason that several Jominian concepts and phrasing can still be found within the doctrines of most modern Western, as well as Russian, armed forces.

This article aims to elaborate on Jomini’s main principle and its derived maxims, as well as on one of his main concepts. That is to say, it will focus on the importance of the concentration of forces at the decisive point in order to gain local and temporary numerical superiority and, as the principal manner to achieve this, the advantages of operating on internal lines of operation, followed by a translation into practical application in order to denote the Ukrainian Kharkiv offensive along the lines of Jomini's theoretical outlook. Before returning to the Kharkiv offensive, it is therefore necessary to briefly discuss his main principle and a number of the various related concepts he devised. But first let’s begin by introducing the man himself.

Antoine-Henri de Jomini

Jomini had a lengthy, although little varying, career, first as staff officer and later as advisor in the French and Russian armies. Serving as aide-de-camp to Marshal Ney in the rank of colonel, he participated in the Ulm-Austerlitz and Jena-Auerstädt campaigns of 1805 and 1806, two of Napoleon’s most successful campaigns. He was promoted to general by Napoleon in 1807, subsequently awarding him the Legion de Honneur and elevating him to ‘baron’ in 1808.

Antoine-Henri de Jomini. Photo Clausewitz.com

In 1813, disappointed after not obtaining another promotion, Jomini switched sides and, although refusing to fight against Napoleon, he became an advisor to the Russian Tsar. In later years he led the Russian army during the Russo-Turkish War in 1828 and helped establish the Russian General Staff Academy in 1832. He advised the Tsar once again during the Crimean War (1854-56) before finally returning to France. There he took on the role of advisor one last time, assisting Napoleon III during the Italian Campaign in 1859.[4]

More importantly, however, Jomini spent most of his life writing a number of treatises and essays in which he tried to formulate a universal theory of warfare. Beginning as a self-taught strategist by reading the works of a whole range of military theorists from the Age of Enlightenment, he published his Treatise on Grand Military Operations in 1804-05, even before obtaining his first staff position. In time, his writings would confirm his own reputation as being one of the leading military thinkers of his day. Napoleon himself was apparently so impressed that he is said to have stated ‘It’s tantamount to teaching my enemies my entire system of war.’[5] Yet what distinguished him from his predecessors most was that he focused on the handling of larger formations on campaign instead of the tactical conduct of battle.[6] According to Jomini, as a result of ongoing technological developments, tactics were subject to continuous change while strategy, on the other hand, could be reduced to universal principles.[7]

His numerous writings finally resulted in the publication of The Art of War in 1838, which can be seen as the end result of all his previous publications. It was written in a prescriptive manner, which was one of the primary reasons his work remained popular for such a long time, because it provided the then newly-established academies in Western militaries with a clearly written and understandable textbook. Furthermore, it allowed even mediocre commanders to achieve success on the battlefield, provided they followed his maxims.[8] Although it did not always turn out that way, Jomini remained one of the most prominent military theorists well into the twentieth century, in some countries even more so than Clausewitz.[9]

Universal principles of war

Writing his Treatise on Grand Military Operations, Jomini was convinced he had found the universal principles underlying the art of war by comparing the campaigns of Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) with those of Napoleon Bonaparte during the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802).[10] Over the course of the Seven Years’ War, Frederick had managed to achieve a number of major victories, while his army was in fact greatly outnumbered. In particular during the campaign year 1757, when he was confronted simultaneously by multiple opposing enemy armies, invading Prussia from different directions and confronting Frederick with a significant numerical superiority.

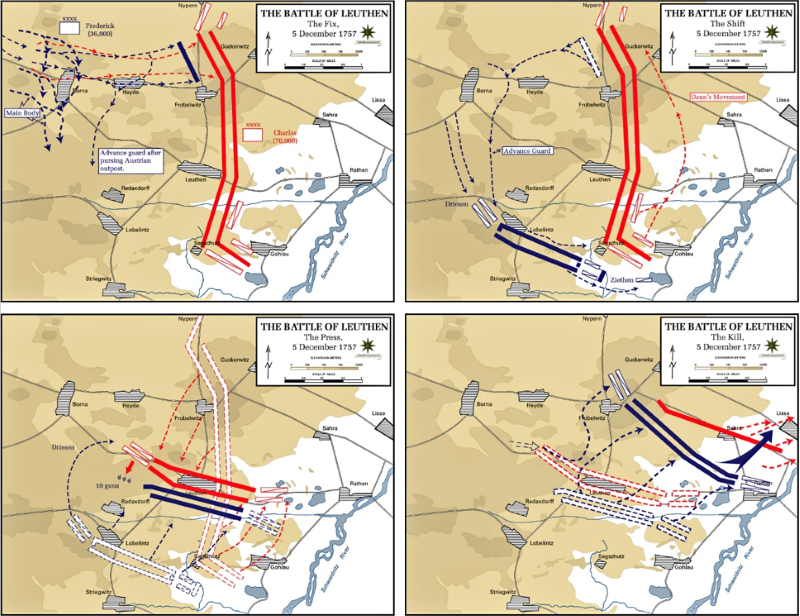

At the strategic level, Frederick resolved this by using his central position, with shorter marching distances towards his individual opponents, compared to his opponents’ greater distance towards each other. This, in turn, created the conditions that enabled him to defeat them in detail, resulting in two of his greatest triumphs, respectively at Rossbach and Leuthen. At the tactical level, on both occasions, Frederick subsequently managed to concentrate the bulk of his forces against a fraction of the enemy army, respectively its advance guard at Rossbach and its flank at Leuthen. Thereby confronting his opponents with a temporary and local superiority in numbers, while they were in fact twice his size.

At the Battle of Leuthen, Frederick the Great managed to concentrate the bulk of his forces against a fraction (the flank) of the enemy army. This way, the Prussians created a local superiority of numbers, despite being outnumbered about 2 to 1 overall. Map 1, ‘The Fix’, shows how a small Prussian force (blue lines) feints an attack on the Austrians’ (red lines) right flank. In map 2, ‘The Shift’, Frederick manoeuvred his troops past the Austrians and surprised them on their left flank. The Austrians tried to bring their right flank into the fray, but their lines where too long. The Prussians pushed the Austrians back (map 3, ‘The Press’). Map 4, ‘The Kill’, shows the retreat of the Austrian troops (source: U.S. Military Academy)

Besides regularly operating from a central position and also, like Frederick, concentrating superior forces against a fraction of the enemy army, Napoleon Bonaparte, during his First (1796-1797) and Second (1800) Italian campaigns, frequently sought to threaten or even cut the enemy’s line of communication and possible line of retreat. Called the manoeuvre sur les derrières, this was to become one of the hallmarks of Napoleonic warfare and would in later years lead to the surrender of the Austrian army at Ulm in 1805 and the destruction of the Prussian army at Jena-Auerstädt in 1806.[11] Campaigns of which Jomini himself was a participant. For Jomini, Napoleonic warfare thus confirmed the characteristics he had identified in the conduct of Frederick’s campaigns during the Seven Years’ War.

Universal theory of war

Based on these observations Jomini arrived at his main conclusion, that is to say: the importance of the concentration of forces at the decisive point, which he then translated into the following four maxims; ‘First, to throw by strategic movements the mass of an army, successively, upon the decisive points of a theatre of war, and also upon the communications of the enemy as much as possible without compromising one’s own; second, to maneuver to engage fractions of the hostile army with the bulk of one’s forces, third; on the battlefield, to throw the mass of the forces upon the decisive point, or upon that portion of the hostile line which it is of the first importance to overthrow and fourth; to so arrange that these masses shall not only be thrown upon the decisive point, but that they shall engage at the proper times and with energy.’[12]

Jomini continued by geographically subdividing what he called the theatre of war into several theatres of operations which, in turn, could be divided even further into multiple zones of operations. The theatre of war he saw as the entire territory in which opponents are able to engage each other in warfare, which he then subdivided into one or more theatres of operations. If within a theatre of operations multiple armies operate towards the achievement of a common objective, then each army does so within its own zone of operations. If this is not the case, however, then each army operates within its own independent theatre of operations.[13] It is this division into a theatre of war, consisting of multiple theatres of operations that is still used today in Russian military strategy.[14]

He then went on to explain that a theatre - or zone - of operations usually contains a number of strategic points, which can be either important geographical locations or locations that derive their value relative to the positions of the enemy’s forces. Those locations exercising a large influence on the course of a campaign he called decisive strategic points.[15] When an army occupies a number of strategic points within a theatre - or zone - of operations, it occupies a linearly-situated strategic front. Finally, when it also includes the adjacent depth to a distance of two-to-three days’ marches from the strategic front, it constitutes a front of operations, which is another phrase or concept that in time would find its way into Russian military strategy.[16] Additionally, those strategic points that are determined to be the objective of the campaign he refers to as objective points, the most important one being the principal objective point.[17]

Finally, and most important for the purpose of this article, Jomini discusses the concept of lines of operations, which are basically avenues of advance consisting of one or more actual roads, linking the principal objective point with its base of operations from which an army derives its logistical support. Lines of operations, therefore, enable an army to conduct strategic movements throughout an entire theatre - or zone - of operations.[18] These strategic movements thus take place in the space between the two opposing forces, inside and beyond the army’s own front of operations.[19]

Although Jomini did not invent the concept of lines of operations, borrowing it in fact from several of his Enlightenment Era predecessors, he did employ a more expansive definition. While his predecessors considered lines of operation exclusively in terms of communication with friendly formations and logistical support from the base of operations, Jomini also viewed them in terms of offensive and defensive manoeuvres, relative to the location(s) of the enemy.[20] In that he differentiated between what he called territorial lines and lines of manoeuvre. While the former constitutes, or hinders, the axes of advance through the geographical outlines of the theatre- or zone - of operations, the latter are also determined by the commander, based on the (principal) objective point(s) and the locations and movements of enemy forces.[21] So, basically, lines of operation enable a commander to follow Jomini’s main principle, namely, establishing a concentration of forces on the decisive point.

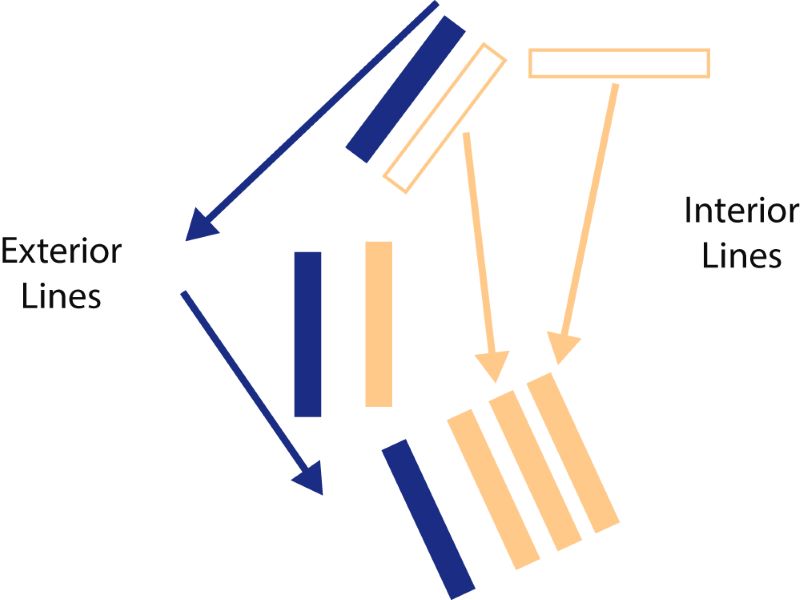

Variations on this include interior and exterior as well as concentric and divergent lines of operations. Interior lines of operation enable a commander to create a superior concentration of forces as a result of shorter spatial and temporal distances against part of an enemy force. This is often used against an overall numerically superior opponent whose forces operate in several separated and dispersed components. As a concept it is related to Napoleon’s (and Frederick the Great’s) use of the central position. Exterior lines form the opposite. By advancing against both flanks of an opponent they are mostly used when an army has superior numbers. Concentric lines of operations, on the other hand, indicate departing from widely dispersed points along a front in order to converge at a specific point. Diverging lines of operations form the opposite as well, by advancing from a single location towards different objectives via different routes by dispersing into several sub-units.[22]

Figure 1 Schematic overview of interior and exterior lines. Interior lines of operation enable a commander to create a superior concentration of forces as a result of shorter spatial and temporal distances against part of an enemy force

Finally, Jomini arrives at his first and most important maxim regarding lines of operations; ‘If the art of war consists in bringing into action upon the decisive point of the theater of operations the greatest possible force, the choice of the line of operation, being the primary means of attaining this end, may be regarded as the fundamental idea in a good plan of a campaign.’[23]

So, strategy, amongst others, includes first selecting the right zone- or theatre of operations, followed by identifying the (decisive) strategic point(s) within that zone or theatre. After establishing one’s own base of operations, the (principal) objective point(s) has to be determined.[24] Only then, central to Jomini’s theory, can the most advantageous line of operations be chosen.[25] The aim is to seize the enemy’s lines of communications, including preventing the exchange of information, the interdiction of supplies and the transfer of reinforcements, without imperilling one’s own, thereby forcing him to battle.[26]

The Ukrainian theatre

Naturally a lot has changed since the days of Napoleonic warfare. Although the Ukrainian and Russian armies currently engaged in Ukraine are not necessarily much larger than their Napoleonic predecessors, the frontline along which they are deployed is all the more so. Where Napoleonic troops had to come together in order to fight a concentrated battle, modern units, due to the increased range and firepower of weapon systems, operate much more linearly dispersed along the front, which itself has also significantly expanded in depth. Additionally, in modern war forces are often permanently engaged and, as such, Jomini’s strategic front cannot merely serve as a point of departure for a strategic advance, ending in a tactical battle, but it is the actual frontline itself.

Another crucial element is that, unlike during the Napoleonic Era, in modern war a concentration of forces can be partially substituted for a concentration of effects. So, when talking about seizing the enemy’s lines of operation, in terms of communication or reinforcements this no longer necessarily means in a physical sense. Instead, modern weapon systems enable armies to achieve certain effects from a standoff distance. For that reason, the essence of lines of operations is transforming from a solely spatial arrangement of combat power relative to the locations of the enemy into a projection of combat power beyond an army’s strategic front.[27]

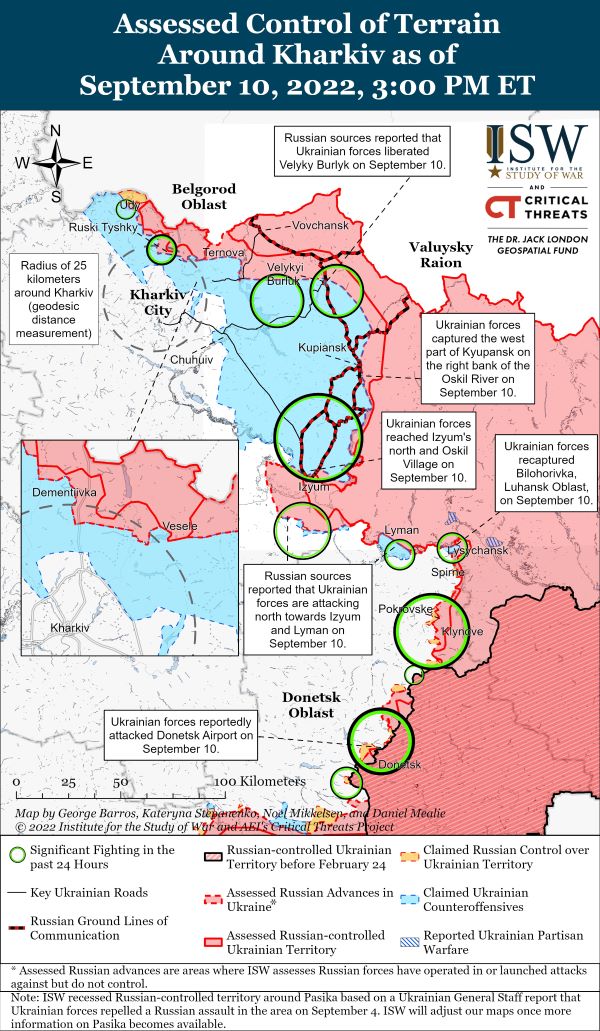

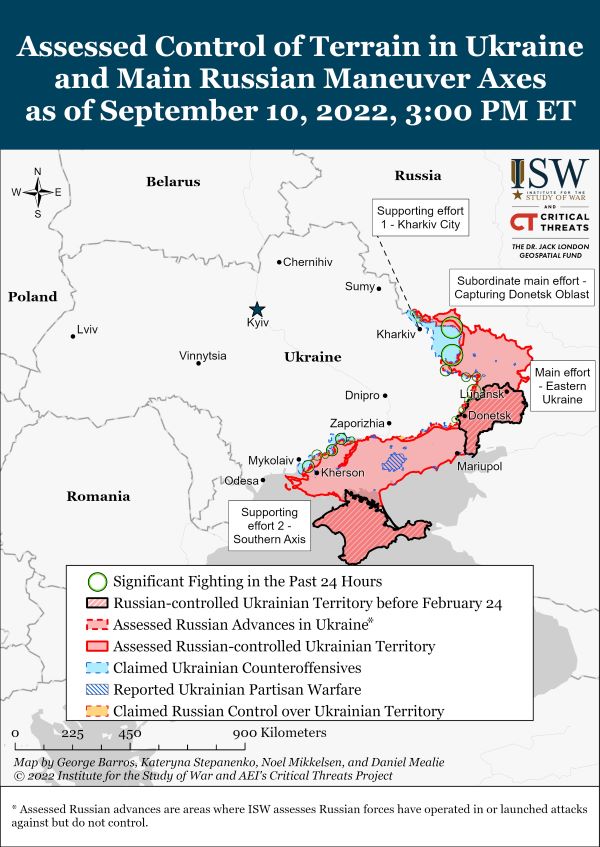

Overview of Ukraine’s offensive in the Kharkiv region, 10 September 2022. Map Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project

What complicates the application of Jominian concepts to the modern battlefield even further is that, in his era warfare was still divided into the realms of tactics and strategy, with tactics referring to the actual conduct of battle and strategy to the movements of armies. Although Jomini indeed used the term grand tactics to refer to dispersed manoeuvres conducted by individual corps and divisions, operational art and the operational level of war did not yet officially exist. Nonetheless, despite these difficulties, it still remains possible to apply certain Jominian concepts into practice on the modern battlefield by identifying the decisive strategic points and lines of operations within a zone- or theatre - of operations.

Regarding the geographical delineation, the term theatre of war can either be used to describe the entire frontline, as it was in the beginning of September 2022, along which Russian and Ukrainian land forces were then actively engaged, or it can also include the inactive (former) frontline along the northern border, operations in the Black Sea as well as the Russian and Ukrainian strike campaigns far beyond the actual front. Likewise, the active frontline can be considered as one theatre of operations divided into several zones of operations, together working towards a common objective, i.e. recapturing all of Russian occupied territory. However, one can also argue that these are actually three different theatres of operations, each of which aimed at a different objective, namely the recapture of Kherson in the south, the battles around Bakhmut in the east and the fighting in the area around Kharkiv in the north.

At the time of the September 2022 Kharkiv offensive, the Ukrainian army did not employ higher level formations such as divisions and corps. Instead, it was organized into four regional commands: west, north, east and south, with brigades operating directly under these commands. Because these regional commands were operating in concert for the achievement of a common objective, for the purpose of this article the former option will therefore be used, with each regional command, i.e. north, east and south, operating in a separate zone of operations.

As a result of the inverted frontline running more or less parallel to the Russian-Ukraine border, the Ukrainian army has the advantage of interior lines of operations. It is therefore able to make use of Ukraine’s extensive road and railway network to move forces around in the different zones of operations. By contrast, the Russian armed forces operate on exterior lines of operations. It has traditionally been dependent on railroads for conducting large-scale troop movements. However, there are no railways running parallel to the front inside Russian-occupied territory. Therefore, in order to transport troops along the front, the Russian army is forced to use railway lines that run all the way from Crimea, across the Kerch Bridge, through Russian territory towards the area around Kharkiv, and vice versa.[28]

Run-up to the offensives

In the course of the summer of 2022, following the heavy fighting around Severodonetsk, Russian forces were steadily continuing their advance westwards towards Bakhmut and southwards from the area around Izyum, with the ultimate aim of capturing the important Ukrainian cities of Slovyansk and Kramatorsk. During that same period, US and Ukrainian officials were conducting wargames in order to determine the most promising avenues of advance for a Ukrainian counteroffensive. Initially, the Ukrainians were aiming at an offensive across a broad front in the south in the area around Kherson. However, the outcomes of the wargames demonstrated that a large offensive against such a strong concentration of Russian forces along the Kherson front would probably fail. Instead, other avenues of advance probably offered more chances of success.[29]

During that same period, without mobilization the Russian army was increasingly struggling to generate enough and sufficiently trained manpower to replenish their worn units. As a result, it was severely understrength and incapable of sufficiently manning the entire 1,000-kilometre front. Meanwhile, in the course of August, significant Russian reinforcements, primarily from 1st Guards Tank Army, were being re-deployed from the area around Kharkiv towards Kherson in anticipation of the widely and deliberately telegraphed upcoming Ukrainian offensive.[30] As a result, the number of Russian battalions around Izyum was halved and left only thinly-stretched and mostly poorly-trained troops behind, primarily consisting of Rosgvardiya[31] units, mobilized LNR troops and some small remnants of 20th combined arms army, 11th corps and 1st Guards Tank Army.[32]

Through Western intelligence, the Ukrainians took note of these Russian movements and were able to determine the strengths and weaknesses along the Russian frontline.[33] Intelligence also estimated the time it would take the Russian army to re-deploy these forces back towards the north in the event of a Ukrainian offensive around Kharkiv.[34] While it would probably take Ukraine a day or two to transfer forces along interior lines of operation towards the north, it would take Russia at least a week or two while using their exterior lines of operation.[35] Instead of one major offensive against Kherson, the Ukrainians therefore planned to conduct two, one in the south towards Kherson and one in the north around Kharkiv, limiting the southern offensive to an assault against the city of Kherson itself.[36] Although this was not a feint or a diversion, it did play a crucial role in supporting the Kharkiv offensive by luring away large numbers of Russian troops.[37] By utilizing their interior lines of operation, they would then be able to establish a concentration of forces against what can easily be described as the decisive strategic point along the northern front, namely the city of Izyum.

Overview of all of the frontlines in Ukraine, as of 10 September 2022. Map Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project

Command of the upcoming northern offensive was entrusted to Colonel General Oleksandr Syrskiy, who had also led the defence of Kyiv during the initial invasion.[38] At the end of August, Syrskiy met with his brigade commanders to lay out his plan, talk through each brigade’s role within the overall plan and discuss possible contingencies. The main objective, or principal objective point, would be to advance via Balakliya towards the city of Kupyansk along the Oskil river and cut off Russia’s ground lines of communication that ran from Izyum towards Russia’s Belgorod region. Syrskiy decided not to attack the cities head on but to bypass them instead, relying on the speed of the advance, threatening Russian troops with encirclement and forcing them to withdraw.[39] Meanwhile, US supplied HIMARS, HARM anti-radiation missiles and target intelligence were used to conduct deep strikes against Russian command posts, radar sites, ammunition depots, logistical hubs and bridge crossings in preparation of the advance.[40]

The Ukrainian offensive against Kherson began on August 29. After quickly breaking through the first line of the Russian defences, they soon began meeting stronger Russian opposition.[41] In the meantime Ukrainian deep strikes continued, targeting Russian bridges and pontoons across the Dnipro River in order to disrupt Russian ground lines of communication around Kherson.[42] While both sides became entangled in positional battles, Russian milbloggers were quick to claim that the Ukrainian offensive in the south had failed.[43] Nonetheless, Ukrainian forces steadily continued to make progress.[44]

Meanwhile, however, a number of Ukraine’s best-trained and most elite brigades were quickly being re-deployed and transferred towards the northern front.[45] In total, the Ukrainians now had five brigades available, 3rd tank brigade, 92nd and 93rd mechanized brigades, 80th air-assault brigade and 25th airborne brigade, together with an independent task force consisting of 10th mountain brigade and several smaller SOF detachments.[46] Although the Russians eventually detected the Ukrainian build-up, they did not have the forces available to halt the offensive and reinforcements rushing in from Kherson would take far too long to arrive in order to halt the impending Ukrainian advance. In this manner, at least according to one Russian officer, the Ukrainians managed to establish a numerical superiority of eight against one,[47] although this is probably somewhat exaggerated.

The Kharkiv offensive

On September 6, Ukrainian forces finally burst out of their assembly areas with 92nd mechanized brigade leading the assault by advancing by way of a number of small roads leading through the farmland.[48] The Ukrainian forces were equipped with an extraordinary amount of lightly-armoured wheeled vehicles providing the necessary speed and mobility. They quickly managed to break through the initial Russian defences and continued the advance, bypassing large population centres and strong Russian troop concentrations and utilizing speed in order to cut off and isolate Russian garrisons (for a detailed overview of the Ukraine offensive, see the map on Jomini of the West’s X account).[49] Confusion amongst Russian forces reigned supreme and with their troops seemingly under attack from every direction, resistance in the area soon collapsed. While withdrawing in disarray, Russian units left behind large quantities of military vehicles and equipment.[50]

By the end of the first day Ukrainian lead elements passed by the city of Balakliya and, after intense fighting, captured its important road junction. The following evening Ukrainian troops were in control of most the city, cutting off a number of Russian troops. Volokhiv Yar was taken that same day, blocking one of just two routes leading towards Izyum on the western bank of the Oskil river.[51] On September 8 the bulk of the Ukrainian forces continued their advance to the north. They linked up near the village of Shevchenkove, where Ukraine’s 113th territorial defence brigade had undertaken a supportive attack on their left flank. From thereon, 92nd brigade, together with 25th and 80th brigades, carried on their advance towards Kupyansk, which was the major road- and railroad hub in the region and formed the main objective of the offensive. Late next day, on 9 September, the Ukrainian advance guard reached the western outskirts of the city and, by late 10 September, Ukrainian forces had cleared the entire western bank of Russian troops.[52]

An abandoned Russian tank in the Kharkiv region. Using multiple axes of advance across the region the Ukrainian army pushed the Russians out of a large area. For fear of encirclement, Russian forces abandoned a lot of their equipment to make a quick escape. Photo ANP, EPA, Oleg Petrasyuk

Although Kupyansk was the principal objective point, Ukrainian forces used multiple axes of advance across the region, resulting in numerous breakthroughs and the re-capture of large amounts of Ukrainian territory. For fear of becoming encircled, many Russian soldiers simply abandoned their equipment without putting up a fight and tried to reach safety by crossing the Oskil river. With the west bank of Kupyansk now in Ukrainian hands, the last remaining and most important ground line of communications from the Russian border towards Izyum was also blocked. At that time, Izyum itself had a garrison of around 10,000 men and enough military equipment to put up a serious fight.[53] Nonetheless, lacking the will to stand and fight, they left the city almost overnight, leaving behind everything that could not be carried. Although the capture of Izyum had not been part of the initial Ukrainian operational plan, when it became apparent that the majority of Russian troops were fleeing the city in order to avoid becoming encircled, Ukrainian forces decided to enter the city nonetheless.[54]

Conclusion

With the re-capture of Izyum the Ukrainian army had achieved a major victory, depriving the Russian army of its main logistical base in the northern part of the front. In Jominian terms, Kupyansk and especially Izyum could be considered as the decisive strategic points within the northern zone of operations. Although in the initial plan Kupyansk was designated to be principal objective point, Ukrainian forces, using the momentum, quickly adapted the plan once Izyum was for the taking. Clearly the counteroffensive was not aimed at destroying the Russian ground forces but instead at capturing these important road and railroad junctions in order to cut Russian ground lines of communication or, in Jomini’s terms, its lines of operations.

Looking at his four maxims, it is apparent that the Ukrainian army succeeded in using strategic movements in order to throw a significant mass of its forces upon one of the decisive strategic points within the entire theatre of operations. The manner in which they achieved this was, firstly, by drawing away Russian reinforcements along exterior lines of operations towards the southern zone of operations and then by using their own interior lines of operations to achieve a local and temporary superiority in numbers in order to engage a fraction of the Russian army. Additionally, both in the run-up to the offensive as well as during its execution, Ukrainian forces conducted deep strikes against all sorts of Russian communications behind the front thus disrupting Russian lines of operation from a standoff distance.

Within the operational/tactical conduct of the offensive, the Ukrainian forces resorted to speed and concentric lines of operation in order to advance, enabling them to concentrate against the decisive strategic point and capture Kupyansk. They established bridgeheads across the Oskil river, which can easily be described as the most important territorial line within the northern zone of operations, thereby blocking most Russian routes of retreat towards the east and interdicting the crucial Russian line of operation that connected Izyum with its base of operation in the Russian Belgorod region, which ultimately resulted in the city’s capture. Besides exceptional timing, they made sure that the offensive would be executed with the utmost energy by assembling some of the best Ukrainian formations for this offensive. Lastly, but equally important, they refrained from advancing too far and exposing their own lines of communication.

Although, compared to the Napoleonic Era, in modern war theatres of operations have expanded significantly in size and the physical massing of troops can nowadays be partially offset by concentrating effects rather than forces, the deployment of large bodies of troops in time and space, concentrated or dispersed, remains the foundation for conducting a successful campaign, especially when airpower on both sides is basically absent. While zones and theatres of operations assist in determining the geographical delineation of an operation and the recognition of decisive strategic points can help to establish the objectives, lines of operations create the opportunities for obtaining the concentration of forces necessary for achieving the principal objective.

Jomini believed in the primacy of operating on interior lines of operations in order to achieve the necessary concentration of forces at the decisive point when confronted by a numerical superior but dispersed opponent. However, as previously stated, an operation never occurs in isolation and is therefore never independent of the adversary’s actions. As was made clear during the Battles of Leipzig (1813) and Waterloo (1815), during both of which Napoleon operated on interior lines but failed to achieve victory. Nonetheless, as the Ukrainian Kharkiv offensive likewise showed, interior lines do provide an advantage and when executed properly, threatening the enemy’s lines of communication, can still result in decisive victory, even in modern wars.

* Captain Randy Noorman, MA works as a staff officer in military history at the Netherlands Institute of Military History.

[1] Alya Shandra, ‘Ukraine’s counteroffensive near Kharkiv: what enabled the Balakliia Blitzkrieg’, Euromaidan Press, September 11, 2022. See: https://euromaidanpress.com/2022/09/11/ukraines-counteroffensive-near-kharkiv-what-made-the-blitzkrieg-possible/.

[2] Mick Ryan, ‘A tale of three generals – how the Ukrainian army turned the tide’, Engelsberg Ideas, October 14, 2022. See: https://engelsbergideas.com/essays/a-tale-of-two-generals-how-the-ukrainian-military-turned-the-tide/.

[3] Mark T. Calhoun, ‘Clausewitz and Jomini: Contrasting intellectual Frameworks in Military Theory’, Army History 80 (Summer 2011) 28. See: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26296157.

[4] Marc Allégret, ‘Jomini, Antoine Henri, Baron de’, Revue du Souvenir Napoléonien 434 (April-May, 2011) 51-53. See: https://www.napoleon.org/en/history-of-the-two-empires/biographies/jomini-antoine-henri-baron-de/.

[5] Allégret, ‘Jomini, Antoine Henri, Baron de’.

[6] Calhoun, ‘Clausewitz and Jomini: Contrasting intellectual Frameworks in Military Theory’, 31.

[7] Azar Gat, The Origins of Military Thought: from the Enlightenment to Clausewitz (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1989) 113.

[8] Calhoun, ‘Clausewitz and Jomini: Contrasting intellectual Frameworks in Military Theory’, 35.

[9] Beatrice Heuser, Paul O’Neill and Antulio Echevarria, ‘Jomini: Selling Napoleon’s System’, Talking Strategy (Podcast) February 7, 2023. See: https://www.rusi.org/podcasts/talking-strategy/episode-1-jomini-selling-napoleons-system.

[10] Calhoun, ‘Clausewitz and Jomini: Contrasting intellectual Frameworks in Military Theory’, 23 and 27.

[11] Gat, The Origins of Military Thought, 117.

[12] Antoine-Henri, Baron de Jomini, The Art of War: restored Edition, translated by Capt. G. H. Mendell and Lt. W. P. Graighill (Kingston, Legacy Book Press, Inc., 2009) 47-48.

[13] Baron de Jomini, The Art of War, 51.

[14] Michael Kofman et al, Russian Military Strategy: Core Tenets and Operational Concepts (Arlington, Center for Naval Analyses, 2021) 40.

[15] Baron de Jomini, The Art of War, 59.

[16] Baron de Jomini, The Art of War, 65; Kofman et al, Russian Military Strategy: Core Tenets and Operational Concepts.

[17] Baron de Jomini, The Art of War, 51-52 and 59-60.

[18] Ami-Jacques Rapin, ‘Rethinking Lines of Operations: Jomini’s Contribution to the Conceptualization of Strategy in the Early Nineteenth Century’, War in History 30 (2023) 31.

[19] Rapin, ‘Rethinking Lines of Operations: Jomini’s Contribution to the Conceptualization of Strategy in the Early Nineteenth Century’, 32.

[20] Calhoun, ‘Clausewitz and Jomini: Contrasting intellectual Frameworks in Military Theory’, 31.

[21] Rapin, ‘Rethinking Lines of Operations: Jomini’s Contribution to the Conceptualization of Strategy in the Early Nineteenth Century’, 31.

[22] Baron de Jomini, The Art of War, 73.

[23] Ibidem, 83.

[24] Ibidem, The Art of War, 46.

[25] Gat, The Origins of Military Thought, 117.

[26] Austin L. Bajc, ‘Improving Maneuver Warfighting with Antoine-Henri Jomini: Warfighting Functions, the Single Battle Concept, and Interior Lines’, Expeditions with Marine Corps University Press (September 15, 2022) 16.

[27] Bajc, ‘Improving Maneuver Warfighting with Antoine-Henri Jomini: Warfighting Functions, the Single Battle Concept, and Interior Lines’, 16.

[28] Thomas Latschan, ‘Ukraine: Will the railroad decide the war?’, Deutsche Welle, May 5, 2022. https://www.dw.com/en/ukraine-will-the-railroad-be-what-decides-the-war/a-61714831.

[29] Julian E. Barnes, Eric Schmitt and Helene Cooper, ‘The Critical Moment Behind Ukraine’s Rapid Advance’, The New York Times, September 13, 2022. See: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/13/us/politics/ukraine-russia-pentagon.html.

[30] Steve Maguire, ‘Yes, Manoeuvre is Alive. Ukraine Proves It’, Wavell Room, November 4, 2022. See: https://wavellroom.com/2022/11/04/yes-manoeuvre-is-alive-ukraine-proves-it/.

[31] Rosgvardiya is the National Guard of the Russian federation.

[32] Isabelle Khurshudyan et al, ‘Inside the Ukrainian counteroffensive that shocked Putin and reshaped the war’, The Washington Post, December 29, 2022. See: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/12/29/ukraine-offensive-kharkiv-kherson-donetsk/.

[33] Barnes, ‘The Critical Moment Behind Ukraine’s Rapid Advance’; Michael Kofman and Ryan Evans, ‘Ukraine’s Kharkiv Operation and the Russian Military’s Black Week’, War on the Rocks (podcast), September 12, 2022. See: https://warontherocks.com/2022/09/ukraines-kharkhiv-operation-and-the-russian-militarys-black-week/.

[34] Barnes, ‘The Critical Moment Behind Ukraine’s Rapid Advance’.

[35] Kofman and Evans, ‘Ukraine’s Kharkiv Operation and the Russian Military’s Black Week’.

[36] Barnes, ‘The Critical Moment Behind Ukraine’s Rapid Advance’; Khurshudyan et al, ‘Inside the Ukrainian counteroffensive that shocked Putin and reshaped the war’.

[37] Barnes, ‘The Critical Moment Behind Ukraine’s Rapid Advance’.

[38] Ryan, ‘A tale of three generals – how the Ukrainian army turned the tide’.

[39] Khurshudyan et al, ‘Inside the Ukrainian counteroffensive that shocked Putin and reshaped the war’; Henry Foy et al, ‘The 90km journey that changed the course of the war in Ukraine’, Financial Times, September 28, 2022. See: https://ig.ft.com/ukraine-counteroffensive/.

[40] Henry Foy et al, ‘The 90km journey that changed the course of the war in Ukraine’; Barnes, ‘The Critical Moment Behind Ukraine’s Rapid Advance’.

[41] Kateryna Stepaneno et al, ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, August 29’, Institute for the Study of War, August 29, 2022. See: https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-august-29.

[42] Kateryna Stepaneno et al, ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, August 30’, Institute for the Study of War, August 30, 2022. See: https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-august-30.

[43] Kateryna Stepaneno et al, “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 41’, Institute for the Study of War, September 1, 2022. See: https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-september-1.

[44] Kateryna Stepaneno et al, ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 4’, Institute for the Study of War, September 1, 2022 See: https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-september-4.

[45] Maguire, ‘Yes, Manoeuvre is Alive. Ukraine Proves It’.

[46] Jomini of the West (@JominiW), ‘#Ukrainecounteroffensive #UkraineWillWin’, Twitter, September 11, 2022, 01:05. See: https://twitter.com/JominiW/status/1568737425597386752?cxt=HHwWgMC-6ZCYo8UrAAAA.

[47] David Hambling, ‘How Ukraine’s Lightning Counter-Offensive Overwhelmed Russian Forces With Humvees’, Forbes, September 15, 2022. See: https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidhambling/2022/09/15/how-ukraines-lightning-counter-offensive-overwhelmed-russian-forces/?sh=791924a97309.

[48] Maguire, ‘Yes, Manoeuvre is Alive. Ukraine Proves It’.

[49] Jomini of the West (@JominiW), ‘ZSU Counter Offensive in the Donbas: 04-10 September 2022’, see: https://twitter.com/JominiW/status/1568737425597386752.

[50] Hambling, ‘How Ukraine’s Lightning Counter-Offensive Overwhelmed Russian Forces With Humvees’.

[51] Khurshudyan et al, ‘Inside the Ukrainian counteroffensive that shocked Putin and reshaped the war’.

[52] Henry Foy et al, ‘The 90km journey that changed the course of the war in Ukraine’; Jomini of the West (@JominiW), ‘#Ukrainecounteroffensive #UkraineWillWin’.

[53] Hambling, ‘How Ukraine’s Lightning Counter-Offensive Overwhelmed Russian Forces With Humvees’.

[54] Khurshudyan et al, ‘Inside the Ukrainian counteroffensive that shocked Putin and reshaped the war’.