In 2024, both Moldova and Romania held pivotal elections that exposed the growing sophistication of Russian hybrid interference. In Romania, online campaigns deploying culturally nostalgic content – what we term cybernostalgia – played a central role in boosting a pro-Russian candidate. Moldova’s presidential elections and EU referendum, though marked by cyberattacks and widespread vote-buying, showed only the early signs of similar tactics. However, with Moldova's parliamentary elections on the horizon in 2025, all indications suggest that the Romanian playbook will be fully deployed. Cybernostalgia – a coordinated use of sentimental imagery, folklore, and digitally engineered memory – is emerging as a powerful tool for shaping political identity, influencing elections, and undermining trust in democratic institutions. Its strength lies in its emotional appeal and decentralised spread, often amplified by artificial intelligence and supported by cyberattacks.

From a military perspective this phenomenon is not merely informational; it is operational. Cybernostalgia has the ability to destabilize societies, divide populations, and prepare the ground for further hybrid actions. For NATO and national armed forces, particularly those like the Netherlands engaged in securing Europe’s eastern flank, understanding and countering cybernostalgia is vital for maintaining resilience, readiness, and democratic integrity.

The 2024 elections in Romania and Moldova revealed how Russian influence campaigns are becoming increasingly sophisticated. No longer limited to cyberattacks and disinformation, they now also employ a new instrument: cybernostalgia. This strategic playbook mobilizes feelings of homesickness and an idealized past to shape political choices in the present. In Romania, it was deployed in full force, while in Moldova it appeared only in an experimental form. However, with the looming parliamentary elections of 28 September in Moldova, a full-scale deployment is highly likely.

This article examines the Romanian case first, then draws lessons from Moldova’s 2024 presidential elections and referendum, before looking ahead to what is at stake in 2025. Central to this analysis is the recognition that cybernostalgia not only undermines democratic processes, but also carries direct military relevance: it heightens vulnerability to hybrid threats, destabilizes societies, and risks undermining security on NATO’s eastern flank. For the Netherlands, as a member of both the EU and NATO, understanding these tactics is essential. Moldova’s experience offers a preview of the challenges that may soon confront other European states, including the Netherlands with its upcoming elections, as well.

Meet Loredana

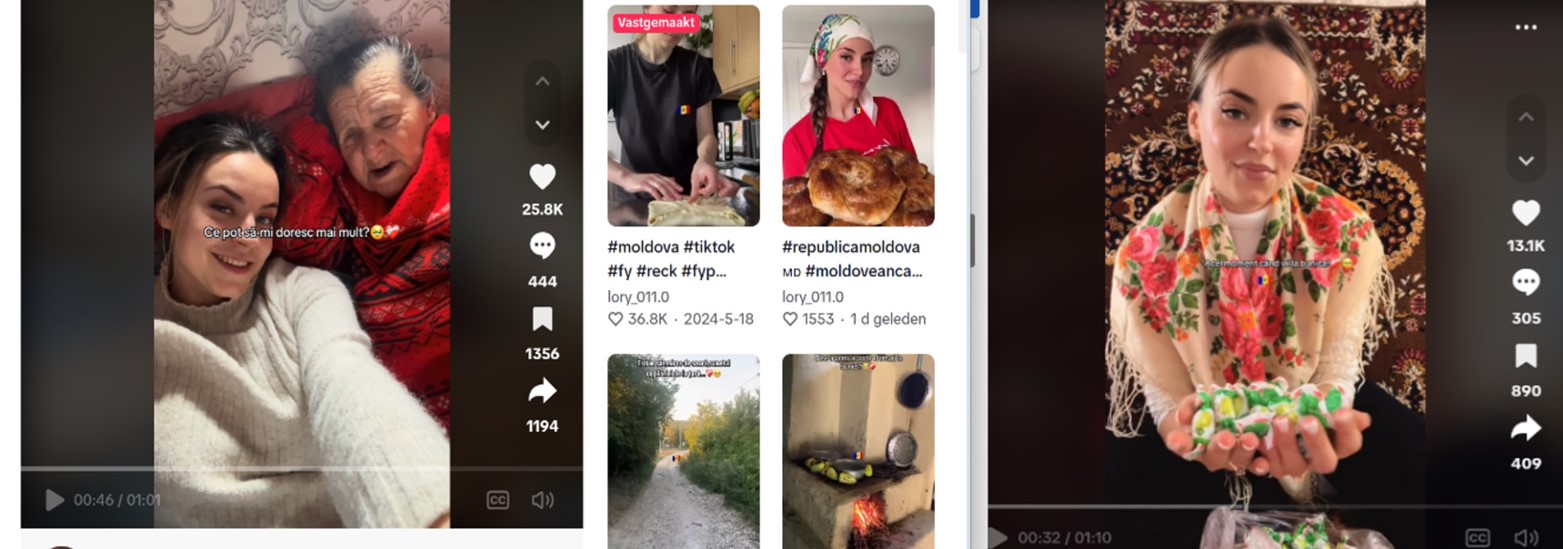

Loredana[1] seductively plucks pieces from her homemade braided bread. She is sitting in front of a wood stove on a floral bedspread. While a Romanian folk song is playing, her humpbacked grandmother, or ‘Bunica’, appears in the TikTok video as an unsuspecting extra. In the background a tv is showing an Eastern Orthodox ceremony.

Loredana is a Moldovan influencer with approximately 60,000 followers and over 1.6 million likes. On TikTok she shares videos of traditional Moldovan country life. By using hashtags like ‘#acasa’ (meaning ‘at home’) versus the hashtag ‘#UK’, she gives the impression of being an expat based in the United Kingdom. In her captions and by using broken heart emojis, she shares her struggle of being torn between her homeland and her diaspora life. The hashtag themes ‘dor’ (sadness), ‘dordecasa’ (homesick longing) and ‘copilărie’ (childhood memories) accompany her nostalgic videos which often receive hundreds of comments.

Screenshots of several videos of the Moldovan influencer Loredana @Lory-011.0 taken in 2025

Loredana is one of many Romanian speaking influencers celebrating Moldovan traditions. She keeps geese, makes traditional stew dishes and, for the eagle-eyed viewers, sometimes has Russian President Vladimir Putin appearing briefly on her tv. While not giving political talking points herself, her comment section is flooded with sentimental comments about missing home, as well as links to Moldovan nationalistic Facebook and Instagram pages. In addition, the followers are inviting others to join Telegram groups aimed at ‘those who are born in Moldova’.

Screenshot of a Born in Moldova Telegram group

The posts, poetry, pictures and videos in the Telegram groups and other social media pages call upon real Moldovans to return to the land where they belong. At times, the comments become more political: ‘vote wisely to help us return home to take care of our elders’. Often they disqualify the views of liberal expatriates: ‘we can’t leave the faith of Moldova in the hands of people that don’t love the country’.

Cybernostalgia

Nostalgia has always been part of the political discourse, naturally following the societal tension between progress and tradition. The original term ‘nostalgia’ ties two Greek words together: ‘nostos’, meaning ‘return home,’ and ‘algos’, meaning ‘pain’ or ‘suffering’. Once seen as a ‘bourgeois’ psychological condition resembling what the Germans call ‘Heimweh’ (home pain) or homesickness, over time nostalgia has detached itself from a longing for an existing home to a more sentimental longing for an idealized home, a sense of belonging situated in the past.

Whilst this ‘traditional’ nostalgia feeds a desire for a home which is not actually attainable, cyberspace has given it a virtual abode in which time, place and social interactions can be reimagined and sentiments can be amplified and intensified. In Moldova, a combined force of nostalgic narratives, coordinated social media take-over and advanced online interference in public infrastructure showcases a determining role of cybernostalgia.

Cybernostalgia can be defined as: a sentiment shared online towards an envisioned better society often rooted in historical, cultural, socioeconomic and political systems of the past. It is characterized by familiarity of online communities, asymmetry of interaction and the use of evolving technology supporting its influence.[2]

Romania: short clips, long consequences

The online countryside-kitsch roaming through Moldova’s cyberspace is not the first example of cybernostalgia. Building up towards the 2024 Romanian presidential elections, many online Loredana’s were appearing and subtly turning political once election day came close. Apart from the homesick expat, social media, and TikTok in particular, saw other traditional archetypes emerge as political influencers. There were the traditional housewives (tradwives) preaching family values against a background of historic eastern orthodox icons. There were the beauty influencers debating the country’s future while applying their ‘#slavicdoll’ make-up. There were the grandmothers giving cooking tutorials as well as leadership recipes. And there were manosphere strongmen promoting supplements as well as anti-immigration viewpoints.

Through coordinated scripts, hashtags and comments, and by cleverly manipulated algorithms, the cybernostalgic content referenced controversial pro-Russian presidential candidate Călin Georgescu. In addition, documents declassified by the Romanian Security Council showed a total of 797 TikTok accounts being identified as actively spreading false content in support of the candidate, some dating back to 2016, the year the app was launched. Many examples of paid promotions for Georgescu funded by Russia were also detected.[3] The Romanian Intelligence Service (SRI) disclosed that it had identified over 85,000 digital attacks which aimed to exploit system vulnerabilities, especially targeting the IT and communications systems supporting the country’s electoral process, during the elections. Furthermore, credentials for election-related websites as well as official Romanian election websites were leaked on Russian cybercrime forums.[4] As a result, the 2024 Romanian presidential election was annulled on 6 December 2024 by the Constitutional Court.

The annulment, and subsequent disqualification of frontrunner Georgescu as presidential candidate in March 2025, eroded trust in Romanian political institutions. Foto ANP

The annulment, and subsequent disqualification of frontrunner Georgescu as presidential candidate in March 2025, eroded trust in Romanian political institutions, with many citizens viewing the decision as a ‘coup d'état’ and protesting in large numbers. The political landscape again shifted as George Simion, leader of the ultranationalist Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), gained prominence and was subsequently backed by Georgescu. Over the course of 2025, cybernostalgic content subliminally promoting both Georgescu and Simion soared. While the content itself showed no blatant violations of social media moderation guidelines, patterns of coordinated bot activity, algorithmic manipulation, fake accounts and cross-social media referencing were evident. Apart from candidate support, sentimental content with folklore, traditional dishes, and folk songs also channelled Georgescu’s and Simion’s ‘Greater Romania’ narratives, including ‘historic’ territorial claims over parts of Moldova and Ukraine.[5] As such, the cybernostalgic content created a hotbed for partition schemes for the future of Ukraine and regional destabilization efforts.

Eventually, the 2025 Romanian presidential elections resulted in a second round victory for the pro-European candidate Nicuşor Dan, but the campaign, heavily overshadowed by coordinated cyber attacks and emotionally charged online narratives, left its marks. While the electoral outcome maintained Romania’s Euro-Atlantic course, serious damage to public trust in democratic institutions was inflicted.

Moldova: when Russia keeps sliding into your DMs

With parliamentary elections scheduled for 28 September 2025, the risk of similar, if not more intense, interference looms large for Moldova. With the best practices from the Romanian playbook and Moldova’s (digital) vulnerabilities well-known, there is every reason to expect a full deployment of cybernostalgia on top of known hybrid tactics aimed at shifting the country’s geopolitical orientation.

When analysing what lies ahead for Moldova, it is worth looking back at its 2024 presidential elections and the accompanying EU referendum which posed the question: Do you support the amendment of the Constitution with a view to the accession of the Republic of Moldova to the European Union?

What initially seemed like a foregone conclusion – polls suggested that incumbent President Maia Sandu would likely secure victory in a single round, with an even stronger majority expected for the constitutional amendment – turned into an unexpectedly tight race. The referendum barely passed with 50,35% voting in favour, and in her run for a second term as President, Sandu, once the clear frontrunner, suddenly faced a competitive runoff. Sandu’s opposition was fragmented, yet united by a common denominator: a greater alignment with Russia’s agenda than with her pro-European course. If their voters coalesced around her opponent Aleksandr Stoianoglo, the second round could become fiercely contested. Given prior expectations for both the election and the referendum, this narrow outcome was an unexpected, if subtle, success for the Kremlin.

The uphill battle the polls suggested did not deter Russia from attempting to manipulate the election through various means. In fact, it launched its largest interference operation in Moldovan elections to date.[6] In addition to the now-standard cyberattacks and threats of violence, there were also large-scale, almost old-fashioned bribery efforts. Ilan Shor (a political pariah who fled Moldova after multiple convictions, including for the notorious one-billion-dollar bank theft, and now resides in Moscow) set up an extensive vote-buying scheme. Expert estimates suggest that nearly 20% of the electorate was approached with financial incentives to cast their ballots and nearly one percent of the country’s GDP (an estimated 200 million Euros) was spent on it.[7] Looking back, Sandu did not mince words: ‘We won fair and square in an unfair fight.’

While her victory reaffirmed the country’s pro-European trajectory, the accompanying referendum on EU accession passed by a razor-thin margin, far below expectations. With parliamentary elections approaching rapidly, Moldova stands at a critical juncture. The aim of foreign interference may not necessarily be to secure an outright win for pro-Russian forces, but to break the parliamentary majority of the ruling Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) and with it, stall or reverse the country’s European course. The tools of disruption have been tested, the digital terrain mapped, and the next contest may well determine Moldova’s political direction for years to come.

Alexandru Musteață, head of Moldova’s Information and Security Service (SIS), has already warned that Russia will again interfere: ‘Their strategy was, is, and will continue in 2025 to be the infiltration of the political environment by individuals and entities affiliated with or covertly backed by the Russian Federation, with the aim of gaining control over Parliament and, consequently, other state institutions. This strategy relies on political and electoral corruption, disinformation and manipulation, as well as street actions and disorder.’[8][8]

Viral memories shaping electoral futures

While the 2024 elections were marked by massive interference, cybernostalgia only played a limited and experimental role. As seen in Romania, Moldovan archetypical (micro)-influencers like Loredana, though varied in socio-economic background, echoed similar themes: anti-European, anti-NATO, nationalistic, conservative, and Christian sentiments. Yet their messaging remained carefully cloaked in sentimental storytelling rather than overt politics. The subliminal nature of their narratives, noticeable only in contrast to their usual lifestyle content, hinted at a strategy still in development. Unlike the more explicit disinformation efforts seen from Transnistrian influencers or traditional paid media figures of Moldova’s political past, these emerging voices operated under the radar: emotionally resonant, but not yet fully deployed. The cybernostalgic effort seemed to lack the scale and orchestration seen in Romania.

In the run-up to the 2025 elections, however, an increase in cybernostalgia along the lines of its three defining elements (familiarity, asymmetry and evolving technology) is taking shape. Special target of these cybernostalgia operations seems to be Moldova’s significant expat community. The country has a population of approximately 2.5 million and an expatriate population of 1.2 million, particularly in Western Europe.[9] As it was foremost the expatriate’s influence that has been decisive in pushing the country toward European integration, cybernostalgia is specifically looking to add fuel to the fire of its divided electorate.

Familiarity

Familiarity refers to the degree to which individuals recognize, know, or feel comfortable with online interaction based on previous experience, repeated exposure, or shared context. While the World Wide Web was introduced in 1989 as a universally-linked information system, some argued that the increased digital connections in our lives created an opposite effect: a stronger search for ‘home’ and a heightened willingness to sacrifice in order to reach it.[10][10] Consequently, people now create their customized (cyber)spaces, where they selectively choose information, connections, and communities.

Moldovans, like many others, have responded to the overwhelming flow of information by carving out personalized online identities and communities. In these (cyber)spaces, users curate what they see, who they interact with, and how they express themselves. Thereby they are crafting digital personas that reflect both national belonging and aspirational identities. For some, this is a way to reconnect with cultural roots; for others, it is a means of distancing themselves from the country’s political uncertainty or economic precarity. As a result, Moldova’s online landscape reveals a growing tension: between global connectivity and a renewed digital search for familiarity, belonging, and ‘home’.

With roughly one third of the population working abroad, the picture of a sympathetic, hard-working expat, pained by leaving children or other relatives behind, is a familiar character to most Moldovans. It is this archetype that plays a central role in much of the Moldovan cybernostalgic content going viral since the 2024 elections. Social media posts contain, for example, references to homesickness or fond memories of Soviet infrastructure, social programs, and aesthetics. The design of the content reveals recurring patterns, including the strategic use of broken heart emojis and hashtags that evoke themes of emotional distress or suffering. Furthermore the content contains elements of folklore, traditional food and drinks, as well as Moldovan flags.

Moldova’s online landscape reveals a growing tension: between global connectivity and a renewed digital search for familiarity, belonging, and ‘home’

A second narrative is that of bitterness among expatriates and the grievances of those left behind. This type of content shows influencers unwilling to depart for work, angry messages towards the current government forcing Moldovans to pursue a better future elsewhere, or descriptions of the poor conditions of migrant workers in Europe. Often this type of content shares hashtags like ‘#strainatate_amară’ (bitter abroad), accompanied by sad folk songs and footage of family members crying and waving goodbye.

Direct appeals to expatriates to come back home contain patterns consistent with emotional manipulation

A third narrative consists of direct appeals to the expatriates to come back home and rebuild a traditional conservative society. This type of content exhibits patterns consistent with emotional manipulation, wherein expatriates are subtly prompted to question whether they are truly aware of their family’s well-being back home. Additionally, the content reveals discriminating undertones by portraying Moldova as a racially homogeneous society, often contrasted with the perceived Islamic influences present in other European countries. Furthermore, this narrative refers to regional instability as a result of the Ukraine war as another reason for expatriates to return home. This latter argument feeds into previous intimidation campaigns that Moldova could become the next Ukraine if it drifts further towards EU and NATO.

‘How was your grandmother?’

A fourth narrative is directly criticizing expatriates who lost touch with their motherland, yet get to vote in the elections. This type of content can be distinguished by the ridiculing of westernized expats and their views on Moldova and the portrayal of Western modernity in a negative light, characterizing it as overly feminized and weak. Content is often accompanied by fake news comments, such as the upcoming sale of the Moldovan army to Romania or the call of the European Commission to hang LGBT flags on state institutions in Moldova.[11] The strategic deployment of online trolls serves to delegitimize content produced by Moldovan expatriates whose perspectives diverge from the dominant cybernostalgic narrative.

Asymmetry

Whilst the element of familiarity feeds into recognisable characters and communities, the second element of cybernostalgia decreases the equality of these relationships through the asymmetry of online communication. On average, a person spends one to two hours a day online, creating an opportunity to reach people frequently throughout the day in a way that feels familiar. Personal accounts are more popular than institutional ones, with individual credibility often outperforming official communication. This leads to a communication asymmetry, where influencers attract more attention than the personal or managed accounts of politicians.

Social media and search engines are the two most popular sources of news and information for Moldovans.[12] Given social media algorithms’ propensity to promote adversarial, controversial, and populist content, posts presenting facts or analysis often remain invisible. Similarly, there is no structured mechanism to cooperate with moderate voices to balance the scales on available information. Instead, while the peak in paid messaging can be measured, it cannot be responded to effectively. Due to this imbalance, cybernostalgia spreads through high volumes of posts and reshares, using existing user networks to distribute coordinated messages.

The infrastructure designed to influence Moldovan public opinion has been systematically developed over time, encompassing a range of tools from malware infected information systems forming large-scale bot networks[13] to (dormant) fake accounts and coordinating (Telegram) channels. Since the 2024 elections, a 2-4 fold increase in bot activity was detected on VK, one of Russia’s most popular social networks. These bots repeated themes from pro-Russian channels in Moldova, attacking pro-European forces and accusing them of being ‘puppets’ of the West.[14] In addition to the increased bot-activity, evidence has in 2025 been presented that social media accounts are impersonating official accounts and trusted media outlets.[15] As was the case in Romania in 2024, these fraudulent accounts are leading to a false sense of credibility and project institutional endorsement. In March 2025, The Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) discovered a Moldovan cross-platform campaign where thousands of coordinated anti-EU Facebook comments led to the identification of a Telegram channel called ЗАПРЕЩЕННЫЙ КАНАЛ, or ‘Forbidden Channel’, which had been created on 13 October 2024. Using a platform analysis tool, the technical analysis revealed 4,484 coordinated accounts as well as 132 targeted pages, primarily news organizations and government institutions.[16]

According to threat intelligence company OpenMinds, there are 133 Telegram political channels in Moldova (as of December 2024), 98 of which represent a negative stance towards president Maia Sandu. Their role is to boost each other’s reach by reposting and commenting on the shared content. While much of the shared content is recognisable as false information or propaganda, a common tactic of pro-Russian channels is to avoid expressing direct sympathy for Russia. Instead, they promote the benefits of neutrality for ‘ordinary citizens,’ often arguing that better relations with Russia would benefit everyone.[17]

President Maia Sandu: the use of influencers, shared scripts, fake accounts, telegram channels and doctored videos can hardly be met by an equal reaction by the government. Foto ANP

The use of influencers, shared scripts, fake accounts, telegram channels and doctored videos can hardly be met by an equal reaction by the government. This asymmetry in action over time is largely in favour of the influencing campaign, primarily due to the features of technology promoting reach over (content) moderation.

Technology

While digital technologies are already used in amplifying familiarity and creating asymmetry, cybernostalgia consists of a third element which entails the proactive use of new and evolving technologies to further support its influence. In fact, much of the content seen in Moldova illustrates technological advances being used to recreate visions of the past. The cyber domain has proven an ideal ground to create false references. Images, texts, sounds, and videos that are ‘hitting home’ are generated faster, cheaper and more realistic than ever before. As this output is relying heavily on evolving AI tools that scrape existing content, stereotypes, clichés and prejudice are easily reinforced. In other words, technological progress is not curing nostalgia but exacerbating it.

Moldovan NGO Stop Fals warns that since November 2024 social media is being flooded by AI-generated content showing people like farmers, workers as well as handmade products (woodcarving or knitwork) to create feelings of pity, faith or patriotism. The AI people in the content are presented as being ‘ignored by society’.

Examples of AI generated content shared on Facebook groups Romania Today, Romania Live, and Traditional Romanesc

The posts attract a lot of comments and engagement, the replies come from accounts emphasizing religious or conservative views. Stop Fals claims that even though the content is in Romanian, the social media channels are managed by people from other countries. Many of those pages also share ‘news’ which lead to anonymous websites. Some experts say this is how messages and audiences are tested, and followers are gained for a future moment when they will start publishing a targeted type of content.[18]

Online campaigns with offline effects

One might ask ‘who is buying this?’ and easily dismiss the dangers of past cliches fueled by new technologies. Actually, we all do. It is almost impossible to reject the nostalgic positivity in home-like sceneries. The urgent problem of cybernostalgia is thus that it works. It is universal knowledge that TikTok is influential, yet, we have been focused on its influence on dance moves, fashion and food. The identities and motivations of content creators remain insufficiently examined, while the diversity and scale of target audiences have been largely overlooked, potentially leading to an underestimation of the content’s impact on Loredana’s fan base. Today’s online homes are weaponizing a distorted vision of the past. In Romania, the stakes went from folklore to border disputes and the repositioning of alliances and partnerships in a matter of months. While Romania is trying to recover from an electoral hangover and restore what is left of its social cohesion and trust in its institutions, who knows what is in store for Moldova?

The best is njet to come

In a recent interview following a crucial energy supply deal to prevent Russian monopoly, Maia Sandu urged European allies to continue military support for Ukraine, saying that Russia wants to gain control over her country and use it as a tool against Kyiv. In her own words: ‘Moscow’s strategy is clear: to exploit Moldova’s vulnerabilities, subvert our democracy and turn our territory into a launch pad for further aggression.’[19]

Cybernostalgia is a strategic campaign tool designed to emotionally reframe geopolitical influence. It calls for responses that are not only technologically savvy, but also culturally fluent, socially viral, and locally rooted. Its decentralised nature, relying on myths, memes, and micro-influencers, makes it difficult to counter. Yet, any form of response should start with targeting its core elements: familiarity, asymmetry, and evolving technology. Doing so may help shift the public gaze from the past perfect to the present tense, prompting a search for accountability and transparency over boosted narratives of a glorified past.

This is what is at stake in the next elections: the question whether cybernostalgia will be successful in preventing free elections. The previous campaigns have proven it can be influential and boost pro-Russian candidates’ chances of winning. Given its early success, it is logical to expect its escalation before the next elections.

Moldova’s geopolitical importance is well established: it borders Ukraine, sits at the edge of Russia’s self-proclaimed sphere of influence, and lies at a critical juncture on NATO’s eastern flank. A shift away from its pro-European course would not only threaten regional stability, but also undermine the broader security architecture. At the same time, the erosion of a democracy already under strain would compound a wider global trend, adding insult to injury at a moment when authoritarian influence is gaining ground and democracies are under pressure.

Moldova is on the frontline of hybrid warfare, facing a complex mix of cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, energy manipulation, and political interference. Its experience offers a broader lesson in how fragile democracies can, or cannot, resist authoritarian destabilization. The rise of cybernostalgia exposes Moldova to soft-power manipulation. Russian-aligned media and online platforms exploit this sentiment to deepen social divides, erode trust in democratic institutions, and weaken Moldova’s Euro-Atlantic orientation.

From a military perspective, this manipulation of collective memory is not just a cultural phenomenon; it is part of a deliberate campaign to reshape the cognitive battlespace. Cybernostalgia undermines institutional legitimacy, divides allied populations, and weakens societal cohesion, all of which erode the resilience required for defence and deterrence. As such, it must be understood as more than a narrative tool: it is a strategic vector within the broader architecture of hybrid conflict. Countering it is not only a task for fact-checkers and civil society, but for military planners and strategic policy makers alike.

Moldova’s 2025 elections are not just a democratic test. They are a security signal.

[1] Loredana [@lory_011.0]. (n.d.). TikTok profile. TikTok. Retrieved May 20, 2025, from https://www.tiktok.com/@lory_011.0.

[2] A. Vos and N. Wojtowicz, Cybernostalgia in Romania: From a past perfect to a present tense (Volten Brief No. 11, May 2025). Centre for European Security Studies. See: https://cess.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/CESS-Volten-Brief_11-2025_EN.pdf.

[3] RFE/RL’s Romanian Service, 4 December 2024. Romanian elections targeted by ‘aggressive hybrid Russian action’, declassified documents show. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. See: https://www.rferl.org/a/romania-russia-election-interference-tiktok/33227010.html.

[4] P. Paganini, ‘Romania’s election systems hit by 85,000 attacks ahead of presidential vote’, Security Affairs, 7 December 2024. See: https://securityaffairs.com/171758/cyber-warfare-2/romanias-election-systems-hit-by-85000-attacks.html.

[5] C. Mihai, ‘Romania’s former pro-Russian candidate under fire over Ukrainian land claims call. Euractiv, 31 Janjary 2025. See: https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/romanias-former-pro-russiancandidate-under-fire-over-ukrainian-land-claims-call/.

[6] ‘How Moldovans bravely fought off Russian election meddling – and stood up for democracy’, The Guardian, 5 November 2024. See: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/nov/05/moldova-russia-election-meddling-democracy.

[7] ‘Moldova says Russian agents spent 200 mln euro to rig votes last year’, Reuters, 2 April 2025. See: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/moldova-says-russian-agents-spent-200-mln-euro-rig-votes-last-year-2025-04-02/reuters.com.

[8] ‘Russia’s Matryoshka disinfo network targets Moldova, bots accuse President Maia Sandu of corruption and repression’, The Insider, 21 April 2025. See: https://theins.ru/en/news/280763.

[9] R. Juarez, ‘Connecting Moldova’s diaspora with the country’s future’, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 15 February 2024. See: https://www.ebrd.com/news/2024/connecting-moldovas-diaspora-with-the-countrys-future.html.

[10] S. Zuboff, ‘Surveillance capitalism is an assault on human autonomy’, The Guardian, 4 October 2019. See: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/oct/04/shoshana-zuboff-surveillance-capitalismassault-human-automomy-digital-privacy.

[11] ‘Disinformation campaign in Moldova’, Check Point Research, 26 March 2024. See: https://research.checkpoint.com/2024/disinformation-campaign-moldova/.

[12] ‘Moldova: Media consumption and audience perceptions research’, Thomson Reuters Foundation, 2021. See: https://epim.trust.org/application/velocity/_newgen/assets/TRFMoldovaReport_ENG.pdf.

[13] Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. IV (1) (2021). Technical University of Moldova. https://jss.utm.md/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2021/03/JSS-1-2021_74-83.pdf.

[14] ‘Russian electoral interference in Moldova and Georgia 2024’, Kyiv Post (December 2024). See: https://www.kyivpost.com/post/43238.

[15] Gwyn Jones, ‘Fake Euronews Telegram channel spreads false claims about Romanian and Moldovan leaders’, Euronews, 11 June 2025. See: https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2025/06/11/fake-euronews-telegram-channel-spreads-false-claims-about-romanian-and-moldovan-leaders.

[16] ‘Cross-platform campaign sows anti‑Europe division in Moldova’, Atlantic Council Digital Forensic Research Lab, 26 March 2025. See: https://dfrlab.org/2025/03/26/cross-platform-campaign-sows-anti-europe-division-in-moldova/.

[17] ‘Russian electoral interference in Moldova and Georgia 2024’, Kyiv Post, December 2024. See: https://www.kyivpost.com/post/43238.

[18] stop.fals.moldova [@stop.fals.moldova]. (n.d.). [Video of false news debunking in Moldova] [Video]. TikTok. See: https://www.tiktok.com/@stop.fals.moldova/video/7470116949389757751.

[19] #####